Australia

A Heartbreaking Mineral Resource Extraction Project of Staggering Muntedness

“The sun is just different here.

I kept saying this to everyone after I got back from my first overseas trip to the West Coast of the United States. On my tour (Contiki of course, IYKYK) I got drunk, had copious amounts of sex, and did so much shopping—back when clothes in the United States were so cheap even with the AUD exchange rate. While the Californian summer temperatures reached heights comparable to those back home, the sun was gentler there. I don’t really know how this is possible: axial tilt? The hole in the ozone layer people talked about in the 90s? In any case, I’ve travelled widely since and maintain that no other place has what Clive James called the ‘opal sunset’ of Australia, where the ‘heat turns your limbs loose’ and ‘eucalyptus soothes the injured air.’

Australians are used to receiving so much natural beauty that they feel no compulsion to cultivate it. Most can walk out their door or go for a short drive and they will be confronted with the sublime. It’s quite absurd. This goes some way to explaining the aesthetic deficiencies of the nation. Natural beauty here is everyday, easy to access. Because natural beauty is both everywhere and so ingrained in the national imagination, a kind of autonomic naturalism obtains in the country’s artistic output. Non- or even anti- naturalism, whether in terms of content, theme, or style, is viewed with suspicion. The Australian Gothic tradition comes close, however its place in the nation’s aesthetic history has been consigned to academic siloes handwringing about settler colonialism. The British settlement of the continent becomes the organising principle for anything that attempts to go beyond the ordinary. Marcus Clarke, an early dabbler in the Australian Gothic mode, wrote of the Australian landscape:

The Australian mountain forests are funereal, secret, scorn. Their solitude is desolation. They seem to stifle, in their black gorges, a story of sullen despair…In the Australian forests no leaves fall. The savage winds shout among the rock clefts. From the melancholy gums scrips of white bark hang and rustle. The very animal life of these frowning hills is either grotesque or ghostly. Great grey kangaroos hop noiselessly over the coarse grass. Flights of white cockatoos stream out, shrieking like evil souls. The sun suddenly sinks, and the mopoke bursts out into horrible peals of semi-human laughter. The natives aver that, when night comes, from out the bottomless depth of some lagoon the Bunyip rises, and, in form like monstrous sea calf, drags his loathsome length from out the ooze. From a corner of the silent forest rises a dismal chant, and around a fire dance natives painted like skeletons. All is fear-inspiring and gloomy.

For literature academics, passages such as these must always be interpreted through the lens of British colonisation. As a British settler, Clarke is ‘othering’ the Aboriginal people and the land itself. Because his ancestors were not original inhabitants, see. But the stark, ghostly beauty of the place can also just be appreciated for its own sake. In a purely empirical sense, Australia is a strange land with strange plants and animals, geologically cut off from the rest of the world millions of years ago. This is interesting and mysterious whether you’re the descendant of British colonists or not.

In Europe, the Gothic is also discussed in reference to historical realities such as the fall of the ancien regime, with all its decayed splendour. But there is not this same critical tendency to reduce it to such concerns. In Australia, it’s always ‘legacy of colonisation this’, ‘dispossession that.’ Commentaries around the Australian expression of the Gothic will flee from the supernatural, the non-mundane, the unique desolation of the country. Here as in other domains, the spectre of colonisation not only works to flatter the ideological commitments of leftist intellectuals, it heads off the possibility of play present in other forms of Gothic literature. For example, the presence of the ‘fantastique’, the supernatural puncturing an otherwise realistic scene, is either ignored or rationalised by a hyperfixation on historical realities. ‘Hey, did you know the mystery of Picnic at Hanging Rock is about the ANXIETY of colonialism? Just like everything else.’ How dreary.

Modern Australian writers, being mostly city-dwellers, don’t properly contend with the terrifying grandeur of the country. Clinging to a few coastal conurbations, they’re unwilling to consider the geo-spiritual interior of the place. Most are avid Acknowledgers of Country, but nevertheless persist in an uncritical postcolonial delusion that the continent has been sufficiently mapped and conquered. The uniqueness of the place as a whole is left underexplored in favour of an undistinctive and always out of date cosmopolitanism.

We are a weird people in a weird land. Perhaps because of this, normiehood is propagandised so forcefully. At the same time, our creative classes preen about their willingness to ‘tell it like it is,’ in a sort of faded pastiche of the larrikin archetype. Yet these types also adhere to a polite, don’t-rock-the-boat artistic version of normiehood. Thus are born the three interlocked literary pathologies of this nation: ideological kow-towing, realism, and ‘seriousness.’

The literary culture’s atmosphere of timidity and consensus is hardly speculative. I’ve experienced it myself. I’ve been to the parties, the talks, the book launches, been on the panels, been published by several of the ‘big’ literary journals. I’m not coming from a place of bitterness about feeling left out. Nor am I afflicted by ‘cultural cringe’, that lumbering rhetorical trebuchet besieging meaningful criticism in Australia. I am relating my observations with honesty and with a critical spirit all too rare in this country.

Luke Carman did the same in 2016. His exquisite jeremiad, Getting Square in a Jerking Circle, described a literary culture more concerned with moral hygiene than artistic risk, where writers are expected to submit to the prevailing tastes of an insular clique of bureaucratically minded ‘anti-artists.’ Nothing has changed in the decade since. Carman depicts a scene dominated by artistic normiehood. People who aren’t weirdos in any sense, governed by fear of stepping outside a hyperliberal line of middle-class decorum. Ambition too is suspect. Australian Literature is held back by the people who run it and the people who want to run it, because it is ‘community’ first rather than art first. As Carman reveals, everyone is risk-averse: writers, publishers, critics, the entire edifice. Like all good bureaucrats, they prefer ideological and stylistic safe harbours.

In this context, realism persists as the hegemonic mode. This is fine as far as it goes, but it tends toward literature easily reducible to cultural concerns and oft-blurbed ‘importance.’ This redounds to style in predictable, if sometimes appealing, ways. From the 70s-90s, there came a slew of drug literature with a kind of spare, desolate style (sometimes called ‘grunge lit’) intended to reflect the spiritual barrenness of the junkie/deadbeat life. The most celebrated was Helen Garner’s Monkey Wrench (which the author long-ago admitted is just her diaries from 70s share house living while in love with a drug addict). Andrew McGahan’s Praise was another prominent example, as was John Birmingham’s He Died with a Falafel in His Hand. It’s all about the disgusting, challenging, filthy reality of drug use. No Naked Lunches here (Burroughs, for all his obnoxious stylistic sins, at least extends his literary powers beyond ‘drugs are yucky, mmmkay’).

Crime fiction, too, is another tributary of this safe edgy realism. The outback noir boom, from Jane Harper to Chris Hammer, gestures toward the uncanny and inexplicable, but only from within the safety rails of procedural logic. Bodies accumulate, wrongdoers brood in dead towns, and landscapes glower in the background. When Australian crime writing edges closest to the Gothic, it must ultimately submit to the rationality of clues, motives, trauma, sociology. Strangeness is permitted only if it can be folded back into the warm swag of realism. This is the same gravitational force felt everywhere in Australian Literature: the demand that the unsettling be rendered safe, that the mysterium be solved and filed.

Alongside this more dirty type of realism is the realism of the middlebrow. Straightforward, competently-constructed stories about suburban or rural lives, or various kinds of historical fiction. Some of it is very good. For example, I am on a crusade to revive interest in Colleen McCullough, whose potboilers (complimentary) overflow with a distinctive style and an exuberant, Fat Woman Vitalism. Tim Winton, Bryce Courtney, and more recent writers like Trent Dalton are other examples of the popular middlebrow style.

Even our science fiction exhibits compulsive groundedness. Australian SF is almost never mind-bending. And these days it often reads like a wonkish ESG white paper from the Australia Institute. If not YA (and most of it is), SF stories here are basically public-policy Powerpoints. The kind with way too many slides.

Samuel Delany argued the great gift of SF is its capacity for ontological shifting, its formally in-built ability to rupture the reader’s sense of reality. Not in Australia. Here, it’s a useful pedagogical tool. It’s very serious, IMPORTANT work. Please no subjunctive delirium or metaphysical vertigo. Our speculative novels must be responsible. I don’t mind naming names: James Bradley is one culprit, continually banging on about climate change, while Claire G. Coleman does the same with indigenous land rights. Both are instructive before they are imaginative. Even when the premise is fantastical, the narrative is yanked back toward the dreary gravity of ‘The Real’, or as I have called it elsewhere, ‘Current Thingism.’ One of the few Australian SF writers who truly plays with ontological shifts is Greg Egan, whose fiction detonates identity, embodiment, physics, and even the concept of the self, but he is mostly published and appreciated beyond antipodean shores. It is not that Australia cannot produce visionary work; it is that our cultural machinery has no way of recognising it unless it comes pre-packaged in moral seriousness or social utility.

Don’t get it arse about: I like realism. Psychological, modernist, hysterical, whatever flavour you can name. But as one style among many. Its reign over this place needs to end. But the problem is not primarily one of form or genre. It’s a sensibility issue. Desiccated notions of ‘social importance’ must go. Crucially, these notions shouldn’t be replaced by new current things.

The new Australian sensibility won’t be midwifed by Creative Writing faculties or arts bureaucracies or the genteel mandarins of Carlton book launches. We need writers who are unconcerned about being on panels and the rituals of purity-policing that pass for criticism here. The old modes of gatekeeping are crumbling anyway. The possibility of real Australian Literature begins the moment writers stop playing by these crusty, anti-artist games.

Australia is the last, strangest child of the New World. It is bound by no inherited style. The future won’t be realist, Gothic, speculative, or avant-garde. It will be all of these and none of them. Nothing limits what the literature could become once writers stop kneeling before the Important and the Real and let the place, in all its deranged sublimity, do its work on them.”

—Matthew Sini

“In 2012, iron ore magnate Gina Rinehart was declared by Forbes as the world’s richest woman, with a net worth of AUD 29 billion. In the same year, she contributed a major piece of public art to her home state of Western Australia: a poem, titled ‘Our Future’, engraved on a plaque embedded in 30-tonne boulder of iron ore which sits at the Coventry Village Shopping Centre in Morley, a suburb of the state capital, Perth. The poem is a tribute to the iron ore industry and a broadside against the government policies and ‘rampant tax’ which hamper it. It is a topic about which Gina understandably feels passionate: iron ore exports contributed AUD 130 billion to the Australian economy at its 2021 peak; they today account for over 40% of Australia’s total export value (the country’s single most valuable export commodity), and have made Western Australia one of the richest regions by GDP per capita on Earth. While Gina is no longer the world’s richest woman, she remains in the top ten, and her latest net worth of AUD 38 billion makes her Australia’s richest person for the sixth year in a row.

It doesn’t matter that Gina’s poem is bad, or puts politics first: most contemporary poetry is, and does. Many critics lambasted the poem, though I doubt they would have bothered if they didn’t already hate Gina for other reasons: for the wealth she has amassed, the wealth she has inherited, for her politics, for her father’s politics, for her appearance, and for her dramatic family history (including that much of her family wealth has gone to a woman she once reportedly called a ‘Filipina whore’). The latest reports are that while the boulder remains, the plaque bearing the poem has been prised off it, possibly due to vandalism or some quiet official decision. To this day, more people in Perth know this poem than any written by the likes of Dorothy Hewett, Randolph Stow, John Kinsella or Charmaine Papertalk-Green.

The billionaire with the greatest aesthetic influence on Perth of all time is not Gina, but Alan Bond, whose tumultuous rise and spectacular fall is legendary. He bankrolled the Australia II yacht that won the 1983 America’s Cup, ending the New York Yacht Club’s 132-year winning streak and giving Australian sport one of its most iconic moments. In 1992, Bond Corporation was placed into receivership with debts exceeding AUD 1.8 billion, the largest corporate collapse in Australian history and one which exposed deep corruption in Western Australian government and industry. The money coursing through Perth in the Bond era gave the city its skyline and the corporate modernist architecture that made districts like South Perth and Scarborough more like Miami than Melbourne.

Australian art critic Robert Hughes claimed that ‘Like many another entrepreneur, Bond had never given much thought to art until he got rich.’ Be that as it may, painted works played an important role in Bond’s aesthetic legacy from the earliest stages of his career:

As an apprentice sign writer, Bond helped to touch up Fremantle’s iconic Dingo Flour sign (but did not, as the myth goes, paint it himself). The sign is a West Aussie icon, having inspired a plethora of merchandise as well as a brand of beer. Bond’s apprenticeship preceded one of his first enterprises: an industrial painting company called Nu-Signs, which Paul Barry claims engaged in ‘skullduggery’ like carrying out works with watered-down paint that would wash off buildings in the wet season.

In 1987, Bond bought Van Gogh’s Irises (1889) at Sotheby’s New York for USD 53.9 million, then the highest price ever paid for a painting (which Bond never paid). The painting was displayed in Bond Tower in Perth and taken on a national tour of Australia, however there are claims that both cases involved a mere replica and that the original never left the United States. In response to public protests at the tour stops, Bond claimed that the trouble with Australia was that it was being seized by a ‘vocal and critical minority which knocks success and resents excellence’.

In 1970, Bond bought purchased 20,000 acres of land for his ‘Yanchep Sun City’ project, a plan to transform the mostly desert coastal area into a satellite city for 200,000 residents. According to Paul Barry: ‘John Bertrand, who was a member of the 1974 America’s Cup crew, remembers his first sight of Yanchep from the passenger seat of Bond’s Rolls-Royce Corniche as they roared up the long coast road from Perth. There were white rolling sandhills stretching into the distance, bordered on the left by the magnificent blue of the Indian Ocean. But there was neither a person nor a blade of grass in sight. Then suddenly, as Bertrand looked again, the sandhills turned bright green, just like an oasis. ‘Christ,’ said Bertrand, looking at Bond, ‘have you put in irrigation?’ ‘No,’ said Bond, ‘I’ve painted the sandhills to make the brochures look better.’ Bertrand couldn’t believe it, but Bond assured him it was true. Waving his hand, he said: ‘just helping the grass along’. In 1977, the project was sold to Japan’s Tokyu Corporation. In 1981, the Atlantis Marine Park was opened in that area, which was closed by 1990 and is now abandoned, but in the heart of which remains a widely loved limestone sculpture of King Neptune. Yanchep was once considered well-outside of Perth’s city limits, but has now been absorbed by Perth’s urban sprawl and was added to Perth’s suburban rail network in 2024.

During his period of incarceration in the late 90s, Bond reportedly painted around 50 artworks. One of these is a portrait of a brothel madam in Kalgoorlie (where brothels have operated in rude health since the 1890s gold rush), which was on display in Kalgoorlie’s Langtree’s brothel for more than two decades, and donated to the City of Kalgoorlie-Boulder when the brothel permanently closed. Another is a portrait of AFL player Peter Matera (of Perth team West Coast Eagles), which was on display at the Langtree’s branch in Burswood in Perth’s inner-east. According to the brothel’s madam, the painting was a ‘major attraction’, and she was impressed by the number of people who came to the brothel to ask, ‘Where’s the Bondy painting?’ She declined offers to sell the painting, explaining that ‘I don’t particularly like the painting, but I bought it because Alan Bond painted it. To me, Alan Bond is the Ned Kelly of Western Australia.’

Bond is not alone in painting images inspired by Australian Football; this is because sport, more than any other form of human culture, is a fountainhead of the Australian sublime. In the 2000s, the West Coast Eagles, then the richest club in the Australian Football League, achieved operatic levels of drama and beauty, the central figure in which was Ben Cousins. Dubbed the ‘Prince of Perth’, Cousins was as famous for his preternatural football ability as for his off-field behaviour, including associations with various ‘Northbridge’ figures (gangsters and bikies ‘so hot they were tropical’), and dizzying, multi-day ‘twisters’ of alcohol, cocaine, ecstacy and meth. Cousins argues that his hard partying was a pressure valve for his extreme focus on the game: ‘I loved that feeling of being dangerously fit. Looking back it was frightening, the adrenaline from life I was getting. I was diving headfirst into everything. After pulling up from a bender and getting into pre-season work, I got so fit, and fresh, that I could only think of one way to burn it off. And so the cycle went on, football and drugs, two insatiable beasts feeding each other.’ According to Cousins’ fellow Eagle Glen Jakovich: ‘if anything, the more trouble he gets into off-field, the better he plays.’ The Eagles made it to the Grand Final in 2005, suffering a disappointing loss to the Sydney Swans. Cousins won the 2005 Brownlow Medal, accepting the award with a mystery black eye; months later, he resigned as Eagles captain for abandoning a Mercedes on the road in Applecross and wading into the nearby Swan River to escape a booze bus. In the 2006 Grand Final, the Eagles avenged their loss against the Swans with a single point win, taking the premiership for the third time in the club’s history. In 2007, Cousins was the last person to see former Eagle Chris Mainwaring before the latter’s death by overdose in October 2007. Cousins promptly relapsed and was soon arrested in Northbridge in a widely photographed incident, displaying his new tattoo: ‘SUCH IS LIFE’ in a down-turned horseshoe shape on his abdomen, believed to be the final words of Ned Kelly as he faced the hangman. This presaged a wild and ignominious decade for Cousins, including an erratic incident where he stood on Canning Highway and attempted to direct passing traffic, as well as a stint in jail for breaching a restraining order taken out by a former girlfriend.

Cousins: ‘There’s’ something about Perth in summer. We were training in beautiful weather, then swimming at City Beach. A few days earlier I’d been thinking, ‘I don’t think I’ll touch a drug ever again.’ But after Friday’s weights session, the end of the week, I couldn’t wait to hop in my car and grab a beer from the drive-through on the way home. Fuck, I’d think, this is going to be a good weekend. How good is this?’

In March 2022, after six years working in corporate law in Hong Kong, I had a moderate nervous breakdown and made an unplanned return to Perth. Within three days of returning, Western Australia dissolved all of its remaining Covid quarantine requirements, and I went outside without a mask for the first time in two years. I had a vitamin D deficiency, two numb hands from carpal tunnel syndrome, and, despite having been signed off work for a year, was incessantly tearful and unsettled. My new psychologist, a barrel-chested water polo player, recommended that I read The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck and commit to a goal, suggesting a half-marathon. Ultimately, I didn’t have to do either; within a few months back in Perth, I started to relax and feel happy again. On the train, I watched Chinese international students point at and take photos of strip malls and carparks and servos, and for the first time in my life, I could see what they were seeing.

The Perth metropolitan area sprawls from Two Rocks in the north to Mandurah in the south, a distance of roughly 150 km. From the west coast to the Darling Scarp, there are roughly 50 km. Save for a thicket of skyscrapers in the city centre, Perth is 6,400 square km of low rise suburb. When you are on the coast, you can see beach to the north and to the south as far as the eye can see, punctuated only by the Port of Fremantle and Alan Bond’s Rendezvous Hotel. The landscape is essentially flat and enormous segments of the horizon are visible, in all directions. For many days in the year, including in the height of winter, the sky is perfectly cloudless and a hallucinogenic blue; at these times, Perth has a ‘metaphysical aspect’ in the manner of De Chirico’s Turin.

It is inane to expect Australian culture to be commensurate to that of Europe, Asia, America or elsewhere. Australia has been part of the Western world for a blink in history, and by the end of my life may well be part of the Sinosphere. We have no Notre Dame; we have Bunnings Innaloo. We have no Sistine Chapel; we have Dôme Café. We have no London Bridge; we have London Court. We have no Ikea; we have Anko. There are some tall buildings in Australia, but, like Perth, it is a spiritually suburban place: it is why Patrick Marlborough wrote that ‘Australia is the Perth of the world.’; it is why I wrote that ‘Perth is now the world’s premiere Australian city, the Australian capital of the twenty-first century.’ It is a place where we cannot resist painting schoolyard art on grain silos and dams, or putting food trucks and cover bands in the forecourts of Brutalist cultural venues. If China’s greatest contribution to world culture in the 21st century is TikTok, Australia’s is Canva, a global reactor core of flat, pastel, family-friendly, safety-first, millennial aesthetics—invented in Perth.

Perth has the calmest atmosphere of any major city you will ever visit. Its people are the most beautiful you will ever meet. Why wouldn’t they be? We are the fittest, healthiest, wealthiest people in the world, enjoying plentiful sunshine, impeccably clear air, and fresh, high-quality water and food, very little of which we have to import. Australia is a place of material abundance and spiritual poverty; here, it is right to acknowledge our extraordinary Indigenous cultural heritage as well as our habit of destroying it. It is too pleasant a place to be spurred by action or ideas, which is why it makes no difference whether we are a republic or a monarchy. It is a place where black swans literally exist, but nothing ever happens. That Australians are relaxed and friendly is our emptiest national myth; we are merely small, something we insist on for ourselves and for each other. We sometimes attempt to make art, and, as set out above, we sometimes achieve it. The rest of the time, we are content to fuss over our houses, second houses, utes, SUVs, 4WDs, boats, families and babies. Like everywhere else, all of this is increasingly expensive and rare. I live with dread that it will all one day come to an end, and yet I know that it must.”

—Liam Blackford

“In the orthodox Australian accent, Australia rhymes with failure (regalia). This is unfortunately not a coincidence but an excellent example of aural determinism. The chief characteristic of Australian art and literature is failure. Not a failure so much of the artist or writer but a failure of their audience. Australian writers, by and large, have not had an audience worthy of them. A small clique of boosters takes pride in any Australian achievement for virtue of its being Australian, without understanding the achievement or even reading it. A larger but still small clique takes pride in any Australian achievement that is noticed overseas so long as it mimics what is popular overseas. Les Murray exploded the brains of this contingent, whose greatest fear is being taken for one of those boorish Australians, by being successful overseas and parochial, patriotic and unphotogenic. Both cliques are more or less invisible to the broader public, although the latter clique dominates the weekend newspapers, where the average person is most likely to hear about new books. The constantly changing mores of the ideology formerly known as ‘woke’ exacerbated the Australian tendency to look to London and New York for cultural cues. This phenomenon, known as the Culture Cringe was described by AA Philips in the now defunct Meanjin magazine in the 1960s. With the importation of American-style wokeness in the last thirty or so years, an entire generation of Australian writers is unable to see their own country and their own people, and indeed themselves, clearly, good and bad. In extremely short supply is an audience that has integrated its parochialism with universalism, both confident and open, able to encourage and support what is best and unique about Australian circumstances without apologising for it, or insisting that Australian culture is anything larger than a twig on the branch on the limb on the tree of European culture.

But what a beautiful twig. As a half-outsider I’m consistently stunned by how little knowledge or curiosity the average edumucated Australian has about their own history and culture, especially literary history. While this does have the salutary effect of putting upstart writers and artists in their place (from which they should emerge stronger) it has the effect of producing bloodless careerist writers with cover letters of perfect length who know how the game is played and are willing to sacrifice vision and quality to get ahead, if they had any in the first place. I kid you not, I once read a contemporary novel where the deus ex machina that solved the protagonists’ financial, emotional and existential problems, the climax of the story, was a successful Australia Council grant application. I am not making this up.

Australia is still home to some of the most practical and skilled people in the world, bush mechanics who can fix a car engine with shrubbery and witchetty grubs. It is home (thanks probably mostly to Irish influence) to some of the most inventive slang outside of old Cockney London. The average Gippsland dairy farmer has a richer, more ‘evocative’ and ‘deft’ vocabulary than the average Miles Franklin winner, and its fair to say also speaks with more ‘urgency’.

That ubiquitous cliche, the ‘forgotten Australian writer’, is sadly more the rule than the exception. The colonial era is almost completely dismissed as an embarrassment; the Hopes, McAuleys, Stewarts, Boyds, even the Hodgins’ are hardly ever read or known by younger generations. Roland Robinson, one of Australia’s most subtle and refined poets and the most successful of the Jindyworobaks, maybe the only true one, lived out the last years of his mortal life in a boat shed. Murray of course is in a category of his own. Lawson was right to tell Australian writers to emigrate or kill themselves. Many have done just that, Peter Porter, Clive James et. al. but I question whether this was best for their work.

Australia’s already small leisure class is fast shrinking. Artistic leisure class families such as the Boyds and the Lindsays produced lasting work. Now, there is a guilt that people who could choose to pursue art full time feel to be middle managers, or worse, university professors or property ‘investors’. They feel as though they need to ‘contribute to society’ and the long gestation of lasting work would be an embarrassment to striver families. Imagine if Joan Lindsay, author of Picnic at Hanging Rock, who lived a tranquil life free from want and clocks in a stunning rural property with her husband Sir Daryl Lindsay, had chosen to waste her life as a j*urnalist or a bureaucrat (same thing) out of some misguided guilt at being rich, instead of using her time and space to write one of the few Australian books guaranteed to be read in one hundred years. I see so much of this kind of waste around me. Australians generally have little understanding of how rich they are. The reason for this is something we call Tall Poppy Syndrome, wherein there is a strong impulse not to admire those of exceptional attainment, but to cut them down, like a tall poppy. Those who genealogise such cultural tendencies locate the origin of Tall Poppy Syndrome in convict camps, or the Royal Navy, but I think it comes from somewhere much more toxic than a chain-gang and is simply the covetous, envious human heart, inflamed to epic proportions in modern bloodless Australia.

Australia with its landscapes and forests of ‘weird melancholy...funereal, secret, stern...’ as Marcus Clarke wrote, has yet to be fully explored in literature. Something about the landscape outside the major cities is wildly distinct from North American or European wilderness. There is so much land and so few people. There are still parts of the continent where no European and perhaps even no Aborigine has ever set foot. Inverted seasons, lyrebirds that can mimic the sounds of chainsaws and gunshots, cuddly koala bears that roar like walruses, delicate orchids growing under drab trees, the famous deadly snakes, spiders, jellyfish, octopi, sharks and crocodiles, which few Australians ever encounter or think about. There is an unbelievable wealth of rich and rare subject matter. Stories of first contact between British and Aboriginal people have not even remotely been fully explored in all their weird and wild variation; Eyre’s journey across the Nullarbor in a woolen suit; the grief of living in a Sydney or Melbourne being transformed before one’s eyes into global anti-cities; a fictionalised Gerald Murnane (fictional); the brutal totalitarian response to Covid in the major cities; rorts, scams, and sports; the nation of gaolers; the lying and obfuscation endemic to more or less every public utterance by anyone of any prominence; daily emperor’s new clothes’ moments; the transformation of a country of yeoman farmers, the pride of the Imperial Army, to a nation of crippled bureaucrats desperate for ‘funding’ and ‘expert advice’; the universal human impulses of love and rage and hunger for God that persist even here at the ends of the known world, all are undertapped sources of inspiration.

Before my rant becomes imprudent let me switch codes. Yes, I code switch. If you know what that means, I’m sorry. The state of Australian Literature is a bit like the state of another beautiful, misunderstood pastime: chess. The four current top chess nations, India, the USA, Uzbekistan and Germany support their players in characteristic, even stereotypical ways. In Uzbekistan, where chess is a matter of national pride, the state supports top players directly. India’s top players are A-list celebrities who enjoy massive public support and corporate sponsorship. One of them is sponsored by Adani, a coal mining company currently hoping to annihilate much of Queensland in the name of delivering cheap energy to Asia. At the recent FIDE World Cup in Goa, Indian players leaving the playing hall were escorted by six security guards through a thronging crowd, like film stars on the red carpet. In the USA, by contrast, a Missouri billionaire named Rex Sinquefield funds a tournament circuit and other chess related activity that basically guarantees a middle-class income to the US top 15 or so. The country as a whole remains indifferent, while German chess players run on pure will and autism. Matthias Bluebaum, who recently qualified for the next Candidates tournament to decide who will challenge the World Champion, doesn’t even have a coach or a second, an absurdity at the top level. To drive home the point, Australia’s two top players through the latter part of the twentieth century lived out of suitcases in Europe. I doubt one in fifty thousand Australians on the street would recognise the names of Ian Rogers or Daryl Johansen. One of our current top players has to earn a living in the grim university sector as a professor of economics and the current Australia number one, Temur Kuybokarov, was born and raised in, you guessed it, Uzbekistan. All of this is to highlight that superfluous beauty has never found ready supports in Australia and this is all to the good, because we have existed in a situation for quite a while now where all official supports, grants, awards, reviews and so on, are incapable of identifying unique talent that will stand the test of time (with some exceptions, obviously). The Australian writers of the future, several of whom are just coming into view, will have to do it for the love of what Czeslaw Milosz called the tournament of hunchbacks. With the kind of freedom only love produces, my hope is that Australian writers will fulfill the promises of the Jindyworobak poets, Paul Hogan and Stephen Bradbury, to produce immortal work of brutal truth and weird beauty for adoring audiences that have been taught to recognise them.”

—Lucas Smith

“Haneke’s Seventh Continent portrays what Australia is to the European imaginary: a place across the world, a different continent, a different planet, a place to escape the suffocating strictures of the old continent monocultures, a place to begin afresh.

Except it is a different planet, the sun is closer to the Earth in the Southern Hemisphere; it’s not the gentle sun of the north, it’s a lethal star down here. It is a rite of passage for newcomers to the Southern Hemisphere: innocently taking a summer stroll and returning with a nose burned to a crisp by the deceptive intensity of the sun. The voyage here is a grueling one; it takes over a week to acclimatise to the time zone and the shock of an instant season change. And none of the seasons align to Vivaldi’s neat concertos. The birds are colourful yet offer no soothing soundtrack to nurture naturalist illusions of pastoral harmony. You will end up next door to people from a country who up until now you probably could not have pointed out confidently on the map, and they are as dazed as you are about this place and how to go about making it home.

Geography is everything. Natural beauty has become an albatross weighing on Europe’s decaying neck for centuries now. An 18th century German goes for a stroll in forests in Bavaria then goes home and formulates a ridiculous theory of history. A Genevan contemporary takes a hike a through the Alps and writes a tome on a ‘universal’ political philosophy that would make absolutely no sense anywhere outside of Europe (and barely does in Europe, but at least you have the extenuating factor that Rosseau was drunk on the beauty of the Alps and the low oxygen brain starvation of high altitudes).

What would Rousseau, Hegel, Kant, or Schelling—those unaware architects of Europe’s current conceptual deadlock—have come up with if instead of the placid rolling hills, neat conifers, majestic Alps and cute lakes of Central Europe they’d grown up in Australia, with its screeching birds, furry groaning eucalyptus leaf eaters, infinite flies, natives with an incomprehensible conception of time, space, and history, needing to resort to bottomless schooners of VB to deal with that sense of immense isolation and the dread of being so far removed from the turning of the great wheels of world history? Kant, if exiled to Australia, would soon become Doc Tydon, the disgraced pansexual doctor of Wake in Fright.

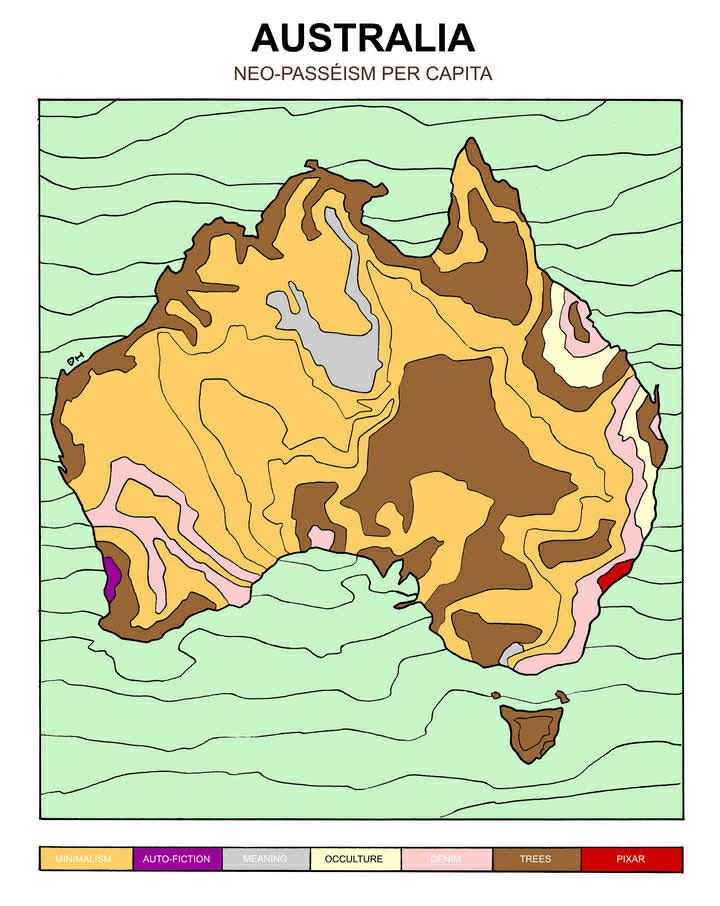

Let us leave aside tendentious issues of land ownership and the hysteria of Australian Neo-Passéists who obsess over the question, reminding us at every gathering that we are on stolen land. The pragmatic reality is simply that millions of people have come here over the past century seeking a better life, drawn by open immigration policies. At two, three, or more generations after the original sin, the psychologically healthy, and most artistically generative approach, is to drop forensic obsessions with past wrongs and the ‘old continent’ traditions of thinking inherited from 18th-century Germans infected with too much postcard-tier beauty and too few deadly creatures. These traditions—Idealism, Romanticism, universalism—wrongly suggest there is a universal harmony that must be returned to, rather than one that must be conjured, pragmatically, temporally-restricted, and localised, out of contingency and chaos. We must instead orient ourselves towards the immediate present and the necessarily arduous task of construction. Here, there is an almost infinite supply of raw materials from which to build.

Deracination and disorientation lend themselves well to originality. Almost everyone here—irrespective of what year their boat dropped anchor or the composition of their Ancestry DNA ethnicity report—is somewhat confused. The shared sentiment that binds one Australian to another is disorientation, in the face of which no amount of guffawing in a slurry local patois about shrimps on the barbie or vegemite or larrikinism or mah great Australian ugliness or lucky country can quite adequately mask the underlying insecurity of a national identity that’s comprised of caricatures scribbled on bog roll paper by drunken English wardens. Australia is a teenager in nation years, hormonal and moody and very horny, looking to the adults in the room for guidance and slowly coming to the realisation that the old nations it once looked up to have been running on pomp and heritage and fraying notions of legitimacy; none of their prescriptions quite make sense for Planet Australia. Go to an old decaying country, and you can find a musty solace in culture (guided tours of cemeteries), renaissance cathedrals, and regional charcuterie specialties. In Australia, we have vast empty beaches that would turn Kant or Hegel into sex pests rather than philosophers and moralists if only to escape the merciless sunlight and the inhuman stretches of empty coastline.

We’re two to three centuries away from the dry comfort of an established identity. We must find solace in each other’s sweaty arms. We must build. We must create our myths from a laundry hamper of mismatched socks, unimpeded by the weight of centuries of history and tradition. Nowhere else in the world exists such a fecund environment for original art and thought; nowhere else is the demand to construct history, rather than simply rest on one’s laurels, quite so urgent. Youth, that brief period of plasticity between childhood and adulthood. We all know the type, the ones that fall for the illusion of endless youth and defer making hard choices until they find themselves mid to late thirties still doing jelly shots on a Friday night, youthful rebellion now a tired cliche.

The worst thing Australia can possibly do is continue to defer to decrepit Europe for values, art, and ideas. It is easy, being a teenager, to be awed by age and adulthood, to listen eagerly to the tepid advice from the aged who haven’t taken risks or lived fully, realising only too late that they squandered their productive years believing that their past glories entitle them to lassitude. Europe is dead, but as places and continents go it’ll take a decade or a century for it to realise this, for now it mistakes its natural beauty and its ancient history for moral superiority, believing that the mass production of luxury beliefs by bureaucrats in Brussels is a viable substitute for contemporary relevance.

Australia is an Orphic Egg of potential. It requires no permission to do whatever it wants, artistically, it can be as affected as NYC or as gritty and authentic as a brothel in a Rio favela. It can be dumb and brawny or intellectual and effete: ideally some combination of both. Importantly, it can choose how much it respects its elders, and how much it decides to forge its own path. The old gods are dying on decrepit continents; nubile Australia need not inherit their guilt and their stale ideas.

One final word of caution: myth-building requires a delicate balance of self-valorization, humility, and cosmopolitanism. Cutesy localism, sentimental stories about ‘good blokes down at the pub,’ and navel-gazing with the rosy lenses of childhood nostalgia only go so far as a writing gimmick; they rapidly degenerate into tedium and self-parody. While no culture completely escapes this trap, America provides a crucial example for cutting ties to Europe and forging a national myth—a journey Australia, now a slutty teenager obsessed with boys and booze, must also undertake to mature into a strutting Camille Paglia, a vamp who does not follow global trends but defines them. The great American writers built their national myth by always seeing its grandeur, even its grandeur in evil. If the great evil necessary for great art was lacking—because the world is often more placid and reasonable than the outrageous unreasonableness artists dream of, and actual evil can be banal—they did not hesitate to invent it completely, ex nihilo.”

—Ivan Niccolai (Notes from the periphery)

“Australian Literature has never really recovered from Ned Kelly’s Jerilderie Letter. Sent in early 1879 from the town Kelly and his gang of outlaw bushrangers were in the process of robbing, transcribed (and probably embellished) by Joe Byrne, the gang’s resident poet—who had previously written and distributed self-mythologizing verses about crimes he himself had joyfully participated in—the letter functions as Kelly’s confession, self-justification and de facto declaration of war on the Victorian government (read: Australia itself as a civic and legal entity). Beginning with a childhood spent stealing horses while punching out treacherous neighborhood adults and progressing to a series of increasingly violent encounters with corrupt officers of the law, Kelly gradually expands the scope of his disdain to include all authorities of the Australian colonial project and, finally, England itself, which he imagines falling beneath an eventual Irish-American onslaught. No amount of paraphrasing can really convey the ferocity of Kelly’s invective, which in its final pages attains heights that surpass all superlatives (‘Biblical’ comes close, but even the trusty Torah pales in comparison), so it’s best to just quote some of it directly. Get ready:

But as for handcuffing Kennedy to a tree or cutting his ear off or brutally treating any of them, is a falsehood, if Kennedys ear was cut off it was not done by me and none of my mates was near him after he was shot I put his cloak over him and left him as well as I could and were they my own brothers I could not have been more sorry for them this cannot be called wilful murder for I was compelled to shoot them, or lie down and let them shoot me it would not be wilful murder if they packed our remains in, shattered into a mass of animated gore to Mansfield, they would have got great praise and credit as well as promotion but I am reconed a horrid brute because I had not been cowardly enough to lie down for them under such trying circumstances and insults to my people certainly their wives and children are to be pitied but they must remember those men came into the bush with the intention of scattering pieces of me and my brother all over the bush and yet they know and acknowledge I have been wronged and my mother and four or five men lagged innocent and is my brothers and sisters and my mother not to be pitied also who has no alternative only to put up with the brutal and cowardly conduct of a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or english landlords which is better known as Officers of Justice or Victorian Police who some calls honest gentlemen but I would like to know what business an honest man would have in the Police as it is an old saying It takes a rogue to catch a rogue and a man that knows nothing about roguery would never enter the force an take an oath to arrest brother sister father or mother if required and to have a case and conviction if possible.

A Policeman is a disgrace to his country, not alone to the mother that suckled him, in the first place he is a rogue in his heart but too cowardly to follow it up without having the force to disguise it. next he is traitor to his country ancestors and religion as they were all catholics before the Saxons and Cranmore yoke held sway since then they were persecuted massacred thrown into martrydom and tortured beyond the ideas of the present generation What would people say if they saw a strapping big lump of an Irishman shepherding sheep for fifteen bob a week or tailing turkeys in Tallarook ranges for a smile from Julia or even begging his tucker, they would say he ought to be ashamed of himself and tar-and-feather him. But he would be a king to a policeman who for a lazy loafing cowardly bilit left the ash corner deserted the shamrock, the emblem of true wit and beauty to serve under a flag and nation that has destroyed massacred and murdered their forefathers by the greatest of torture as rolling them down hill in spiked barrels pulling their toe and finger nails and on the wheel. and every torture imaginable more was transported to Van Diemand’s Land to pine their young lives away in starvation and misery among tyrants worse than the promised hell itself all of true blood bone and beauty, that was not murdered on their own soil, or had fled to America or other countries to bloom again another day, were doomed to Port Mcquarie Toweringabbie norfolk island and Emu plains and in those places of tyrany and condemnation many a blooming Irishman rather than subdue to the Saxon yoke Were flogged to death and bravely died in servile chains but true to the shamrock and a credit to Paddys land What would people say if I became a policeman and took an oath to arrest my brothers and sisters & relations and convict them by fair or foul means after the conviction of my mother and the persecutions and insults offered to myself and people Would they say I was a decent gentleman, and yet a police-man is still in worse and guilty of meaner actions than that The Queen must surely be proud of such heroic men as the Police and Irish soldiers as It takes eight or eleven of the biggest mud crushers in Melbourne to take one poor little half starved larrikin to a watch house.

What would England do if America declared war and hoisted a green flag as its all Irishmen that has got command of her armies forts and batteries even her very life guards and beef tasters are Irish would they not slew around and fight her with their own arms for the sake of the colour they dare not wear for years. and to reinstate it and rise old Erins isle once more, from the pressure and tyrannism of the English yoke, which has kept it in poverty and starvation, and caused them to wear the enemys coats. What else can England expect. Is there not big fat-necked Unicorns enough paid to torment and drive me to do things which I dont wish to do, without the public assisting them I have never interefered with any person unless they deserved it, and yet there are civilians who take firearms against me, for what reason I do not know, unless they want me to turn on them and exterminate them without medicine. I shall be compelled to make an example of some of them if they cannot find no other employment If I had robbed and plundered ravished and murdered everything I met young and old rich and poor. the public could not do any more than take firearms and Assisting the police as they have done, but by the light that shines pegged on an ant-bed with their bellies opened their fat taken out rendered and poured down their throat boiling hot will be fool to what pleasure I will give some of them and any person aiding or harbouring or assisting the Police in any way whatever or employing any person whom they know to be a detective or cad or those who would be so deprived as to take blood money will be outlawed and declared unfit to be allowed human buriel their property either consumed or confiscated and them theirs and all belonging to them exterminated off the face of the earth, the enemy I cannot catch myself I shall give a payable reward for.

And, at last:

I give fair warning to all those who has reason to fear me to sell out and give P10 out of every hundred towards the widow and orphan fund and do not attempt to reside in Victoria but as short a time as possible after reading this notice, neglect this and abide by the consequences, which shall be worse than the rust in the wheat in Victoria or the druth of a dry season to the grasshoppers in New South Wales I do not wish to give the order full force without giving timely warning. but I am a widows son outlawed and my orders must be obeyed.

The middlebrow Australian novelist Peter Carey was inspired enough by the letter to base an entire book on it, although Carey’s polished middle-class sensibilities aren’t able to match anything like the level of vitriolic invention that Kelly (and, again, we suspect, Byrne) produced. Constrained by novelistic conventions, Carey is concerned with moving units and winning prizes, while Kelly is concerned with informing his enemies that he intends to personally kill them in the very near future and dismantle their entire civic infrastructure shortly afterwards. Given this different scale of priorities, there was never any hope of Carey matching the intensity of his source material. But he was correct in stating that the Jerilderie Letter compares favorably with the work of James Joyce (not yet born at the time it was written). Kelly, apprehended after the climactic gunfight in which he donned his famous homemade armor, was subjected to the form of literary criticism known as hanging. In a turn of events the Situationists would have recognized, his rage against the state was recuperated after he was turned into a mere folk hero and national icon; his image now adorns T-shirts and cheap airport gift store merchandise. More people have probably seen the middling Heath Ledger film bearing his name than have heard of the Jerilderie Letter.

Half a century later, imaginative fury would emerge in Australia again under the aegis of Max Harris, the young poet and editor of the Angry Penguins journal, which began publication in 1940. Inspired by avant-garde movements and contemporary European Modernism, Harris sought to move Australian art and writing away from its banjo-strumming provincial concerns, hoping to mold it into something complex, dynamic and new that could stand on the world stage. The artists he promoted abandoned Victorian Realism for bright Fauvist boldness, while Harris’s own poems blew bush ballads up into Ezra Pound-style freakouts about public suicide and ‘pelvic roses.’ Predictably, no one at home was terribly pleased; it didn’t help that the outspoken Harris was also young, handsome and well-dressed. Charges of ‘putting on airs’ were the least of his worries. The traditionally-minded poets James McAuley and Harold Stewart cooked up a plan to ‘get Maxie’ by hoaxing him with an invented poet; to this end they used the cut-up method to produce The Darkening Ecliptic by ‘Ern Malley’—intended to be the ne plus ultra of absurdly ‘difficult’ Modernist verse—and sent it over to Angry Penguins. Sample stanza:

Magic in the vegetable universe

Marks us at birth upon the forehead

With the ancient ankh. Nature

Has her own green centuries which move

Through our thin convex time. Aeons

Of that purpose slowly riot

In the decimals of our deceiving age.

It may be for nothing that we are:

But what we are continues

In larger patterns than the frontal stone

That taunts the living life.

O those dawn-waders, cold-sea-gazers,

The long-shanked ibises that on the Nile

Told one hushed peasant of rebirth

Move in a calm immortal frieze

On the mausoleum of my incestuous

And self-fructifying death.

Harris, suspicious of the frequent absurdity of the Malley poems but accepting the work as a seemingly genuine homegrown explosion of Australian Modernism, published it in full. He was immediately hit with the one-two knockout punches of an obscenity trial (the poems, in their tortured way, allude to sexual encounters) and the revelation of the hoax. Bankrupt, and with his reputation destroyed, Harris retired from both poetry and publishing.

It’s worth pointing out the role that the recently defunct (and for a long time, completely irrelevant) Meanjin journal played in undermining Harris from the start. In its Autumn 1944 issue, Meanjin published A.D. Hope’s review of Harris’s novel The Vegetative Eye, his attempt at an Australian Ulysses, which came complete with an original Sidney Nolan cover painting. Hope, firmly in the Stewart and McAuley camp, jumped at the chance to tear down the twenty-two year old Harris, whose novel, whatever its actual merits, was at least crazily ambitious and genuinely straining at the limits of Australian literary expression:

It reads like a guide to all the more fashionable literary enthusiasms of the last thirty years. Mr. Harris doesn’t miss a trick. In that period, William Blake has been treated as a serious thinker. Mr. Harris leans heavily on Blake. In that period, England discovered Freud, the discoverer of the Unconscious. Mr. Harris explains the Unconscious. D.H. Lawrence discovered that the blood is a more important thinking organ than the brain. Mr. Harris’s conclusion is ‘a suffering from the heart of darkness and the statement of the blood.’ Proust developed the microscopic eye. Mr. Harris has a microscopic eye. Surrealism has become a vogue. Mr. Harris is painstakingly surreal. James Joyce used multiple literary parallels as a method of illumination in Ulysses. Mr. Harris keeps us entangled in a network of literary parallels. Dostoyevsky wrote novels on two levels of consciousness. Mr. Harris writes on so many levels at once that he whizzes from one to another with the mechanical agility of a lift driver. Various writers have used the stream of consciousness technique for telling a story. Mr. Harris’s stream of consciousness has as many tributaries as the Amazon. Baudelaire gave us an example of the artist as the analyst of his own moral sickness. Mr. Harris is morally sick and discusses his symptoms with the gusto of an old woman showing the vicar her ulcerated leg. The death-wish has become a popular theme among modern writers, and Mr. Harris’s death-wish should make him a bestseller in more cultured undertaking circles. Rilke develops the theme of the duality of nature in its evolution toward the perfect consciousness of the Angel of the Duino Elegies to which finds approximations in the child, the lover and the hero. Mr. Harris gives us pages of paraphrased Rilke and incidentally misquotes the Fourth Elegy…the current jargons of literary, esthetic, psychological, social and philosophical studies ride Mr. Harris’s pen like a nightmare.

Seventy years later, it’s difficult to take this criticism in the sense that Hope intended it; surely no worthwhile writer in the present could truly be wounded by being termed too reminiscent of BLAKE, JOYCE, RILKE AND BAUDELAIRE. The Meanjin of seventy years ago was already infected with the simpering philistinism that finally caused its expiration, even if ‘wokeness’ hadn’t been invented yet: and somewhere the ghost of Max Harris laughs darkly at its demise.

And yet, The Vegetative Eye has been out of print ever since. You can Google it if you want: next to nothing will come up, and even Australian small presses don’t seem concerned with rescuing it from obscurity. For comparison, this is a bit like if García Lorca had written a Spanish Modernist doorstopper while having Picasso as his cover artist and then been told to go home and sleep it off:

‘You’re trying a bit hard, mate. Here, have a beer and don’t get above yourself. Consider a career at Bunnings.’

What other country treats its writers this way?

A final example. Joan Lindsay’s Picnic at Hanging Rock is rightly regarded as a classic. But it still isn’t widely known that the novel was mutilated prior to publication, having its final chapter removed. The publisher’s reasoning was simple: the final chapter departs from the mysterious but predominantly realist mood of the rest of the novel, revealing the ultimate fate of its missing heroines, who (SPOILER) aren’t simply abducted or eaten by wild beasts but instead end up interfacing with an alternate region of existence that seems to transcend normal time and space, after which they undergo a series of startling physical and spiritual metamorphoses and perhaps pass out of conventional existence altogether. As the scholar Yvonne Rousseau discusses in her analysis, it’s unapologetically Occult, and forces the reader into consideration of areas of thought and experience only hinted at by the rest of the novel. It also WORKS, and lifts the whole book into a kind of transcendence. So, of course it had to go.

The missing chapter wasn’t published until 1988, as a slim standalone volume entitled The Secret of Hanging Rock, and it quickly went out of print. The critical consensus has ignored it entirely, and to this day, there is no ‘complete’ integrated version of the novel: the current Penguin editions and the like are effectively Bowdlerizations. Those wishing to read the novel as Lindsay intended must print out and append a PDF of the final chapter, which, while it can certainly be done, is laborious and absurd. Again: what other country would do this to perhaps its most prized book?

We can sense a pattern emerging here: Modernistic and genuinely threatening literary expression is met with literal execution by the state (Kelly), reputation assassination and lawsuits (Harris), and censorship (Lindsay). Is it any surprise that Australian Literature didn’t get up to much in the 20th century? A lone genius, Gerald Murnane, was allowed to operate more or less unmolested, although it’s worth noting that domestic reception of his work was muted until very late in his lifetime, and even the eventual embrace came largely from international pressure to recognize the Nobel-worthy writer. Australians themselves seemed to prefer a soppy mediocrity like Tim Winton, who showed them only their own self-flattering fantasies. Book after book of soft focus pap, rural rigamarole and sentimental surfing stories poured out of Winton, who was handsomely rewarded with foreign prizes for playing the Australian show dog; Carey and other lauded writers rarely ventured much further. Australian Literature was seen as a charmingly roughshod sideshow, and Australian writers seemed happy to conform to type. After what happened to Max Harris, it wouldn’t do to get too difficult or ambitious, much less try to match Europe at its own game.

But things have moved on: American writing has mostly sunken into nostalgic navel-gazing and Internet-addled idiocy; England itself dodders; and Australian Literature deserves better. Tall Poppy Syndrome aside, Oz’s persistent hostility to its imaginative elements might have been functioning all this time like the sort of martial arts dojo where they punch you in the back of the head as you enter: if you stick around long enough to make it through the excessive and mean-spirited hazing, you’re probably going to emerge truly toughened and deadly. Anyone in the country independently writing books without giving a shit about the parasitic and incestuous university scenes and publishing industry cliques is surely stubborn enough to ignore the lack of immediate rewards and soldier on regardless. When your own culture doesn’t even want you to win, what would the opinion of dilettantes overseas count for? The independent Australian writer of the present has nothing to fear from hothouse weepers in New York and inhibited London grant-grabbers.

Will 21st century Australian Literature finally break the slump? It seems that, at the least, the old restrictions no longer apply with any force: ‘industry clout,’ ‘wokeness,’ and ‘popular appeal’ have all become toothless. The Australian writers of the moment who matter are no longer beholden to either domestic scene politics or international expectations. Ambition is rising again, and with it, honesty: recent books by Lewis Woolston, Jack Norman (Thingol) and others have embraced a hard-edged, clear-eyed Post-Naturalism: tightened, expansive prose; a deep local investment combined with world class range. Where they will take things from here remains to be seen, but already the curse is lifting. Ned Kelly would be proud.”

—Justin Isis

art by Dan Heyer

football by the Fremantle Dockers

"Australia is the last, strangest child of the New World. It is bound by no inherited style."

Probably that is technically New Zealand...

Amazing work