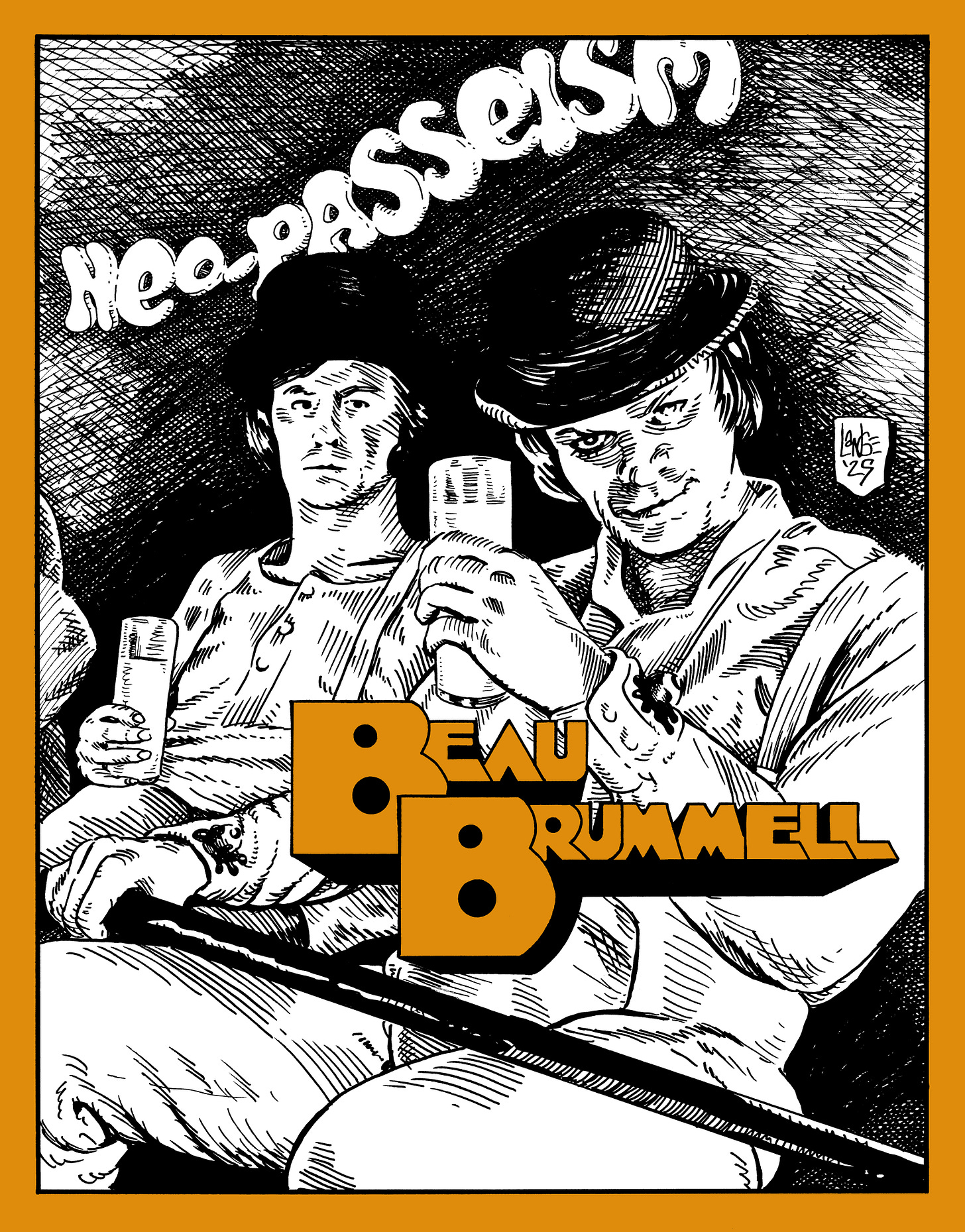

Beau Brummell

Dandy but Not Fine

“Meanwhile Butler’s dictum ‘A man’s style in any art should be like his dress—it should attract as little attention as possible,’ reigned supreme, though only since Brummell had this stranglehold of convention been applied to what we wear.”

— Cyril Connolly (1938)

“We have nothing but contempt for the quaint revivalist who favors the fancy dress of the 18th or 19th century, including all spiritual descendants of that syphilitic dullard Beau Brummell. Similarly, we have no concern with masculinity defined as the mere absence of conventionally feminine traits—neither in the regressive sense of affirming it, nor in the naively reactionary sense of protesting it. Rather than macerate male style in a welter of agonized self-contradiction, we prize stylistic experiments incorporating the expansion of its true sentiments and tendencies: the priest-astronaut’s tenderness, the barking accountant’s ferocity, the chemist-poet’s hyena-like persistence.”

— Neo-Decadent Manifesto of Men’s Fashion (2020)

“Can we blame Beau Brummell for Patrick Bateman? Don Draper? Whatever—we are utterly bored with the ‘Western-style’ Brummell-derived suit, the ultimate slave costume of the capitalist class: clothes for anonymous corpses to be buried in. The same cliches echo through nearly three centuries: ‘quiet luxury’ and ‘understated elegance.’ It would be a pleasant change if elegance chose to DECLARE itself for once, since its continued reticence is really much more distressing than ‘the death of God’ could ever be, and the persistence of Brummellwear is as much an indictment of the human race as any number of more conventional atrocities. Why are we, the electronic eminences of the new millennium, Technological Humanity, splitters of atoms, engineers of genes and flâneurs of the moon, still garbing ourselves in the manner of a British arriviste from the 18th century, a penurious corpse who was fond of cravats? As for the Neo-Decadents, we renounce Renunciation and demand that our poets and artists should be as extravagant, flippant, ‘degenerate’ and irredeemable in the sartorial sense as they are in any other, spiritual and literary alike.”

— Justin Isis

“I am, by no means, a fashionista. My knowledge of the modern fashion world does not extend beyond repeat watching of House of Gucci, and I pay little to no attention to the fashion stylings of celebrities, with the one and only exception to that rule being Lady Gaga (okay, Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus. Okay, Lady Gaga and Miley Cyrus and Kim Kardashian). Like a pheriannath resident of Frogmorton, I am more than anything a creature of comfort, what one could call a T-shirt and jeans guy (or, when lounging around the domicile, a T-shirt and plaid flannel pajama bottoms guy), a man who owns almost nothing in the way of brand name clothes, and who has been known to shop in the bargain section of Walmart’s clothing department on occasion, when in a suitable mood. I am, however, a student of history, so naturally, the evolution of clothes and fashion trends is a topic which I have more than a fleeting interest in, and as a writer of fiction, I’ve found descriptions of the clothes my characters are wearing to be a useful way of quickly fleshing them out in the shorthand (as Polonius sagely advises his son Laertes in Hamlet, ‘apparel oft proclaims the man’). Also, while I myself am not a clothes horse, I still live in a world where I have to see how other people are dressed on a daily basis, so the very least they can do is dress interestingly for my benefit. Now, with that out of the way, let me briefly pause so that I may switch from the personal ‘I’ to the pluralis majestatis, and then we may begin.

To get a clear visual example of the stagnation that has afflicted men’s fashion over the last 200+ years or so of Western culture, one needs only to flip through a copy of What People Wore When: A Complete Illustrated History of Costume. Prior to the 1800s, one can see how varied and interesting men’s fashion used to be, yet post-1800, like some vestiary extinction boundary line, it generally ossifies into a numbing sea of duochromatic suits and tuxedos, with little in the way of variation or excitement. One can also find depictions of this disturbing trend in the arts. Consider “Bal Masqué,” the 1880 painting by Charles Hermans. It depicts a typical masked ball of that era, and looking at it, one can see how the women present are all wearing colorful, exotically frivolous, and eye-catching dresses and outfits, of a variety of styles. The men, on the other hand, are uniformly nothing more than walking clones of tuxedos and top hats, each one visually identical to the next; the very opposite of frivolity, they are the face of grim conformity. We can even see modern examples of this in any manner of Hollywood awards ceremonies: the women get to dress up in manifold and interesting ways, while the men are forced to go the usual boring black and white tuxedo route (with some outliers, of course). It’s almost as if we are trapped in some dreary simulation that has been hijacked by the Penguin’s fashion sense. Granted, there have been attempts to shatter this suffocating paradigm through acts of sartorial transgression, such as the brief period of Glam Rock (and its resulting experiments in androgyny) in the 1970s, and certainly many male pop stars of the 80s were willing to experiment with at times gender-bending alternative fashions (I’m thinking of the likes of Boy George, Martin Gore, and so on). Is it any wonder, also, that we have seen an explosion in the popularity of drag queen culture over the last few decades, representing as it does (among other things) an arena that lets men not only get in touch with their feminine side, but also dabble in more unorthodox fashion styles? This can be seen, we feel, as a rebellion not only against the stifling orthodoxy of the Great Male Renunciation, but also its most well-known figurehead, by which we mean the British creature Beau Brummell.

Brummell was a fixture of the Regency era, an era that would have been otherwise forgotten in the West were it not for being prominently featured in the third series of the acclaimed British sitcom Blackadder. Looking at Mr. Brummell’s biography, we see he at least had some admirable qualities, in that he was something of a proto-Dandy, though that method of cultural self-expression would not reach its apotheosis until the end of the 19th century, and in terms of both wit and artistry he strikes one as a poor man’s Oscar Wilde (it also must be noted that Brummell’s claim to fame was his emphasis on the cravat, yet even there we feel he was eventually overshadowed in that department by the advent of Quentin Crisp). And we also can’t entirely despise a man who was so decadent he had his boots washed with champagne. Yet even these positive qualities do not absolve him of his chief sin, for it can be argued that it was his pestilential example that led to the general acedia of men’s fashion. We suppose the faintest praise we may assign to Mr. Brummell is that he strikes one, at best, as an example of the Early Installment Weirdness of Dandyism, although as stated above, he was quickly eclipsed by his far superior descendants. While on the subject, we will opine that even Dandyism has become a cultural dead end, a more well-groomed example of the serial killer idolized by edgelords, nothing more than an empty signifier worshipped by tattooed moustache-waxing men who work at microbreweries from Portland to Hoboken, along with other post-hippie trash.

Like a cravat-sporting necromancer, the Lich of Brummell continues to posthumously inflict his outdated fashion on the children of the XY chromosome. Previously in this piece we pointed out some ways in which men have rebelled against Brummell’s maleficent influence, but certainly we can think of some other suggestions: Ithorian chaos geishas, interspace navigators with Dolphin chromosomes, Yoshitaka Amano watercolor silks, the blood-red robes worn by the gynecological surgeons (as designed by Denise Cronenberg) in the film Dead Ringers, etc. In the West, we need to make royalty great again, and perhaps the best place to start would be in the wardrobe department: a return to crowns and robes, cloaks lined in ermine and arms graced with long floor-trailing tippets. The possibilities are potentially endless.

The final word here should go to the current head coach of the Boston Celtics, Joe Mazzulla, who once interviewed for a job with another team (the Utah Jazz), and complained about having to wear a suit for the process, something he vowed never to do again: ‘they’re useless.’ To paraphrase X-Ray Spex, Oh Brummell! Up Yours!”

— James Champagne

“Beau Brummell did nothing wrong. Just as all young men should, he rejected the conventions set by the old men of his time and the standards for behavior which they represented. In that context, revolution meant foregoing the ostentatious dress which had become the aristocratic uniform. Absent gaudiness, his style nevertheless required obscene attention to detail and perfectionism at a minimum—traits we should observe with envy. His chief failure was being poor and short-lived, consequently leaving his legacy to the whim of the elite society he successfully defrauded. No one with sense feels pleased with the direction men’s fashion has taken since Brummell’s heyday, but his freak degenerate fans (Victorians) deserve a lot more blame.”

— Will Pelletier

“When I began writing this contribution I wasn’t yet aware that the 2025 Met Gala’s theme would be Black Dandyism. Given this most auspicious timing, we’ll begin thusly:

Dandyism is a rebellious act. The context in which it is a rebellion manifests differently across time and cultural interpretation. But the constant factors in dandyism revolve around an intentional curation of self, often against the forces of society around the dandy.

This may, at first, seem ill suited when considering the Dandyism of George Brummell. Brummell was not an aristocrat, despite his style appealing directly to the aristocracy that hosted him. His origin was by no means pauperly, but he was born on the back of political clout over any ancestral claim to power. He was a military man but hardly more involved than to claim service. He was wealthy, because his father had served under government officials. As far as identity went, Brummell was a relatively well-to-do commoner.

So his rebellion against this adequate existence was to become more aristocratic than the aristocracy. To become so composed, so possessed of his persona and style, that he became sought after by the highest of the upper classes. This desire to be wanted isn’t necessarily the motivation for a dandy, but the pursuit of self positioning and existence is.

While Brummell’s decline came at the hand of his belief in his station over monarchs (as well as his crippling gambling addiction), he succeeded in boldly creating a space for himself, which further influenced the style of men centuries past his austere reign. He was championed as the last dandy by both Barbey d’Aurevilly and Baudelaire, but their appraisal of his life is often tied to their cynicism toward the rising middle classes.

Aristocracy was crumbling during Brummell’s time (which is directly connected with Brummell’s access TO society) and he excelled his betters in truly existing through his meticulously crafted existence…to a point. His life was always going to teeter on the edge, because the compulsion to exist maximally is inherently opposed to the safeties of old money and station. You burn brighter, and fall far faster.

The connections to Black Dandyism, Queer Dandyism, and the Post-Aristocratic modes of dandyism coalesce under the idea of occupying space; the middle and lower classes and marginalized groups struggle differently to occupy the stages of broader society. Despite the trappings of democracy, the society we’re burdened by in 2025 is just as hostile to the concept of rising above your authoritarian-assigned station as ever.

The Neo-Decadent Dandy exists as a Post-Democratic Dandy, as do the Black and the Queer Dandies. Democratic dandies are a uniquely mid-20th century creature, birthed by the fragile years in which the possibility of a brighter, more just world glinted against the backdrop of sudden and total annihilation. They were rebelling against the banal tastes of popular culture, commodifying it and declaring themselves the arbiters of what commonality should be appreciated.

This definition does more closely align with Andy Warhol, as George Walden argues in the forward of his translation of Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly’s Du dandysme et de George Brummell. However, I further associate Democratic Dandyism with John Waters' pursuit of filth and obsession with showcasing the absolute abyss of humanity. Waters himself is a Dandy, both in dress, and through his immaculate self-curation in habit and presentation juxtaposed with his work. To me, Waters marks the transition of the Aristocratic and the Democratic Dandy into something beyond the notion of influencing mass appeal. Waters is the prototype of what becomes the Neo-Decadent Dandy.

The Neo-Decadent Dandy is one that can plainly see the cyclical nature of tyrants: political tyrants and Tyrants of Style alike. As we slip beneath the waters of a boiling post-democratic reality, the aristocracy rises anew, just as beige, just as blighted as any ruling class before them; they lack vision yet are convinced they are the pinnacle of humanity and culture to the degree that they are the true arbiters of taste.

Adherents to Brummellian Dandyism will exclaim that the obliterating taupe they crave is the new Dandyism. To be controlled, to be unbothered, to be uniformly unsullied by seed oils or peasants is the height of human existence. To be as white as snow and forever cradled in that icy womb as their lessers decay and stain themselves in toil.

The Neo-Decadent Dandy has no use for status, least of all status generated through ignorance. These new Dandies curate themselves through the reality that the world is far brighter, intricate and more beautiful than the myopic visions of the elites. That beauty is entrenched in the finest fabrics but also the humblest of meals. Knowing the world, and rejecting thought-terminating fears of otherness is paramount in becoming more distinguished than the ruling classes claim to be as they lay swaddled in self-aggrandizing religion and stylistic conformity.

This new Dandy rejects formulaic style. Suits are fine but they must be compelling in cut, color, or fabric. They read out of curiosity, not to follow the latest trends. They write, or most of them should write, because the literary world is as equally marred by vanilla aspirations as fashion and cars. Their passions draw from the thrum of lived existence in effort to champion that beauty.

They uphold and celebrate the rebellious nature of Black and Queer Dandies by honoring their histories, and very likely sharing in them, because the quest to create the world you want has never ended. But only dandies seem to know how to achieve it. You burn brighter, you are aware of the precipitous decline, but to live a whole and expressive life in the face of tyranny is more important than alluring the tyrants. But they will be nonetheless, as the undeniable chartreuse of Neo-Decadent Dandies seeps and sullies the beige it touches.

Dandyism itself is forever about so expertly crafting your existence for yourself that the world cannot help but notice. It is rebellious, a vital force well beyond a bespoke suit. It is the audacity to give enough of a shit about who you are and the respect you have for yourself that the world cannot penetrate that armor. At least for the little while the flowers bloom and the dandy rests among them. That consumed space is sacred.

The Neo-Decadent Dandy is rapturously sullied by worldliness and poisoned by unutterable truths. But they will proclaim them through unrelenting adornment.”

— Hadrian Flyte

art by Aaron Lange

>the ‘Western-style’ Brummell-derived suit, the ultimate slave costume of the capitalist class…

When Charles II introduced the proto-men’s suit to his court (cravat and open jacket over waistcoat were the fateful innovations, I think), hoping to establish a new cutting edge, Louis XIV responded by making his footmen and lackeys dress the same way. I’m no fan of the Sun King, but this has to be one of the better examples of inter-monarchical pwnage I’ve ever come across.

Fashion sense from a guy who shops at Walmart when he isn’t sitting at home in his pyjamas smelling his own farts: peak abject post-modernism