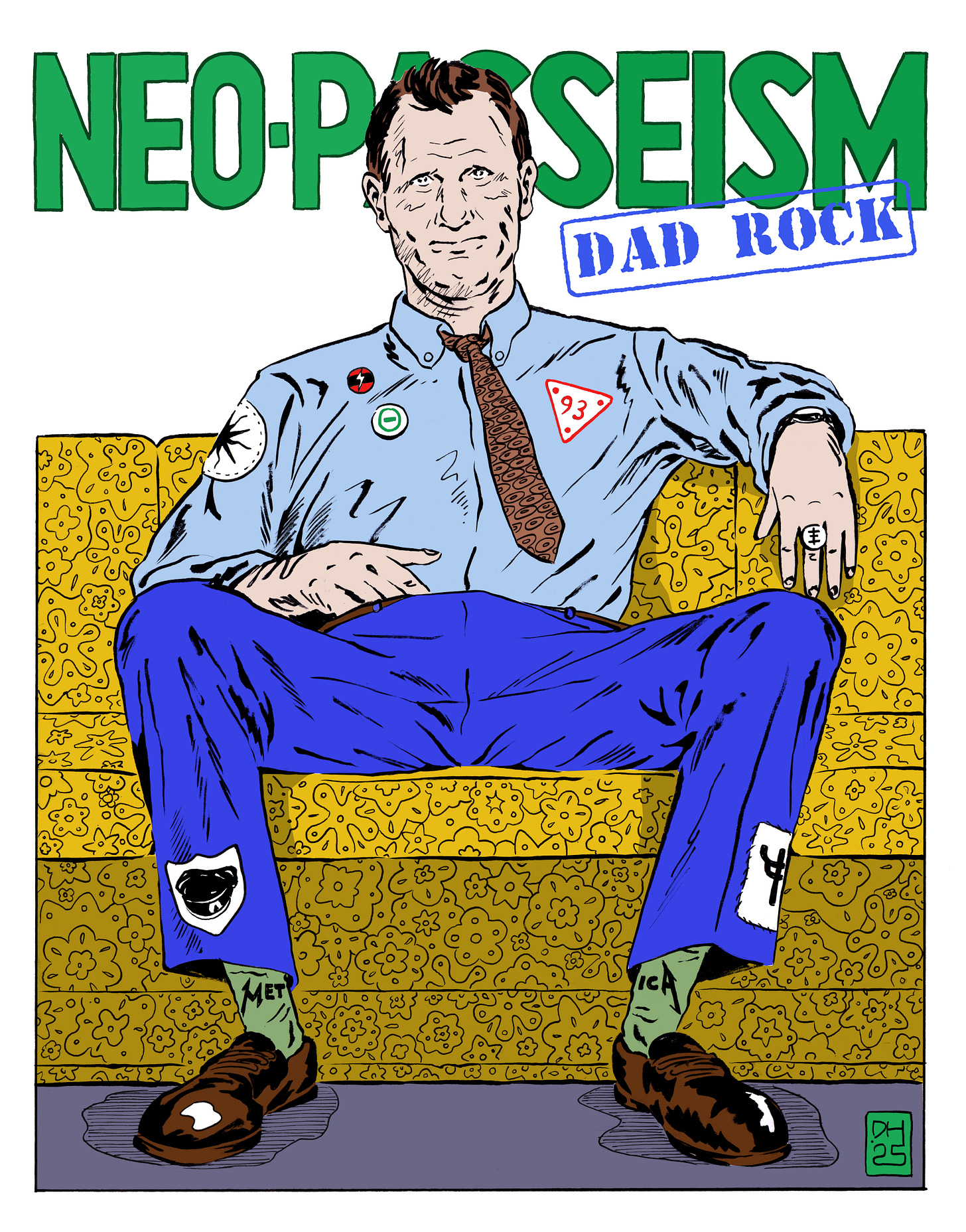

Dad Rock

Throbbing Einstürzende Dad Cave Gristle Electronics

“Those SS uniforms make you feel powerful. They make you feel good about yourself.”

— Ralph Fiennes

“The kids who wore METALLICA shirts every day in 20th century American High Schools eventually subdivided into countless (for someone as lazy as this writer) categories of Dad Rock. These Dads I mention are easily identifiable by continuing to wear band shirts to any occasion; they wear them to shows, dinner with their partners’ parents, drinking IPAs with the boys, funerals, etc. The worst offenders wear their ‘battle jackets,’ which imitate the ‘cuts’ of 1%er biker gangs, but instead of adornment that implies that they murdered cops or members of rival gangs, these Dads’ jackets display poorly sewn patches of band names, edgy images, clever slogans, buttons, and safety pins. Scandinavian Fascist-fashion-fetishists TURBONEGRO later proved my point loudly by providing unofficial charters to ‘Turbojugend’ fan clubs in cities around the world who constructed cuts with top and bottom rockers and club symbols that were a direct imitation of the American biker insignia.

The Metalheads that draw a straight line back to the head-banging bands like Metallica and MEGADETH are identifiable now by, almost to a man, closely shaved heads. When the weight of their 80s-90s ass-length hair caused the middle to fall out, no other hairstyle other than the skinhead cut was acceptable. It is hard to overstate how much the act of head-banging was a part of that early American metal scene; it was as ubiquitous as the pogoing had been in late 70s England, with the added element of needing the hair to really make the magic happen. Metallica would have to pressure its guitar player KIRK HAMMETT to ham it up more and more with his hair-banging, when he was new in the band. The people with the longest, thickest hair were unicorns in the community. The cult of PETER STEELE of TYPE O NEGATIVE was largely based on this, and so fashion-centric and strong that the man used a picture of his asshole as a record cover, to great acclaim by his fans. This is the logical and inevitable end of the Roman road endurance of the style of ultra gay icon ROB HALFORD and the Leather S&M style he covertly unleashed on an unwitting American generation. American Metal is centered on the male anus.

“With the black leather comes the heroin.”

– Johnny Rotten

The Doom and Sludge (‘Sounds like problems a plumber would have’) metal scenes have existed in stasis since SLEEP and CANDLEMASS made their viscous versions of the riff-based triumph of MOUNTAIN or BLACK SABBATH. ACID BATH and EYEHATEGOD took the natural step in the 90s of making the dressings of this style more aggressive, offensive and abrasive. This style remained untouched well into the 21st century, seen in bands like PIGS. All black, mil-surplus and frayed cutoff. Not crossing the line into try-hard Black or Death Metal, certainly not to the degree of DEATH IN JUNE, but like what those MORBID ANGEL or MAYHEM guys wore at home. The dedication to style and self-destructive lifestyle of these folks is to be commended, even if the black and pessimism and suicide and nihilism can get boring quickly.

The Stoner Metal bands are much the same, as early bands like KYUSS and its children existed as time capsules, adopted a decade plus by WEEDEATER, ZOROASTER or SERPENT THRONE, wholesale, but openly fetishizing drugs. The later bands’ addition is their beards, which have turned grey over time and become the symbols of the community, constitutionally bound not to be changed, much like THE RAMONES haircuts and outfits. Some interesting moves were made away from that stasis by bands like DEAD MEADOW, who also refused to be bound by the equally Neo-Passéist Psych Rock scene. Heroin is all over these scenes though, self-pitying and sad. Allegedly, the Bass Player of Dead Meadow and some guy who looks an awful lot like this writer got caught shooting up in a porto-john at Austin Psychfest 2008 and both almost got fired from their bands. I bet they were in that shitter because they were bored with the fashion victims around them and their rules about what you had to be to be in their bands. They may have discussed that. I bet their boots looked great but didn’t fit right, and that the embroidered beads were falling off their shirts. Whatever, Psych Rock is Dad Rock.

All this music became Neo-Passéist so quickly because it was based in these static, boring fashions. Like the Mods and the Rockers, this type of Dad Metalheads and Psychedelic disciples had their day with the trad Punks. And like them, the relevance of their artistic style faded quickly, even if their physical presence didn’t. I’m looking at you, THE EARL in Atlanta. The internal and external conflicts within these groups and their identities as generational punks and fashion victims is an ever-present part of what they are and do. I am scared for their children.”

—

“The Dadlike musical projects of Throbbing Gristle, Nurse with Wound, Current 93 and Death in a June must give us pause. The amplified, mumbling British idiom combined with extremely basic instrumentation and inartful noise does not inspire confidence. That these ‘musical’ acts are often considered to transcend their performance context and impinge on the realms of the literary or philosophical seems to be a fundamental error, and one compounded as their prime periods of musical creation recede further into the past. There seems to be little that elevates them above Big Band, Merseybeat and other forgotten genres—which, in contrast, by virtue of their current obscurity, contain the possibility of unexpected inspiration. A true ‘transgressive’ would seize upon the genuinely unfashionable and outdated rather than relying on popular ‘avant-garde’ signifiers that have corroded over time into predictable badges of mediocrity. As it stands, the entire ‘industrial music’ and ‘neofolk’ category is the Daddest of the Dad.”

—

“It is one of Lady Fortune’s crueler caprices that, with a mere spin of her great Wheel (and in collaboration with the corrosion of ‘that bald sexton Time’), pop and rock bands who pioneered studio experimentation (the Beatles, the Beach Boys), captured the rebellious energy of youth (Rolling Stones), pushed the lyrical boundaries of rock lyrics into a more literary strata (the Doors), or explored taboo/transgressive subject matter (Velvet Underground), are brought low and reduced to the next generation’s background elevator muzak, audio inducement in commercials to purchase smart phones/weight loss drugs/SUVs, blared from the speakers of inconsiderate motorcyclists who wish to broadcast their ‘rebel’ status by rocking out to Tom Petty’s ‘Runnin’ Down a Dream’ for the ten zillionth time, and (most ignominious of all) fated to be covered by creatively bankrupt no-talent non bands as musical accompaniment to the latest overblown Hollywood movie trailers. And while it could be argued that this shouldn’t diminish the prior accomplishments of the bands in question, there’s no denying that their perdurable Inmost Light is frustratingly obscured by all this cultural detritus, a situation ironically amplified by the Baby Boomer mandarins who, desperately eager to maintain their chokehold on Western pop culture, would be content to drag us all down into their Era of Stagnation, and if it takes TikTok commercials of Mick Fleetwood on a skateboard drinking Ocean Spray cranberry juice while lip-singing to ‘Dreams,’ so be it. Sadly, this Eternal Recurrence has even begun to infect people of mine own generation: every time a zoomer wears a Nirvana T-shirt ironically, a Gen Xer smugly smirks and a fairy dies. Bummer, as they said back in the day. Whilst on this subject, it also must be stressed that ‘Dad Rock’ is a term that can be applied not only to what is popularly dubbed ‘Classic Rock,’ but also to genres as diverse as punk, industrial, metal, and so on. The same can also be said about rap and hip-hop. In regards to the latter, despite the fact that they’re as old as I am, there are still natheless some segments of the population (primarily music critics obsessed with coming off as ‘hip’ and out-of-touch members of the white liberal academia) who remain under the delusion that rap and hip-hop remain cutting-edge and innovative musical formats, when in fact they’ve become just as ossified as the boomer rock they long eclipsed back in the 1990s.”

—

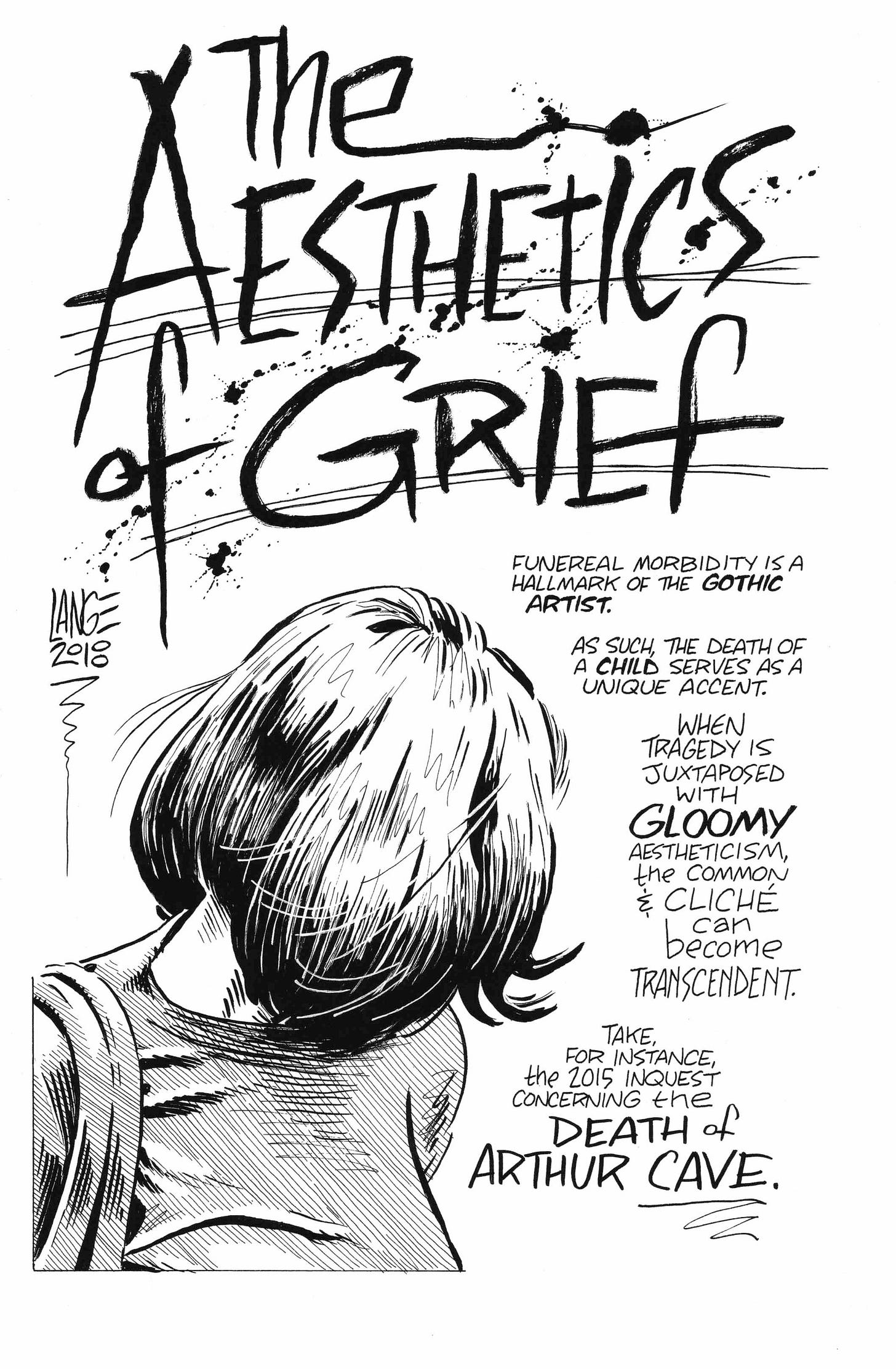

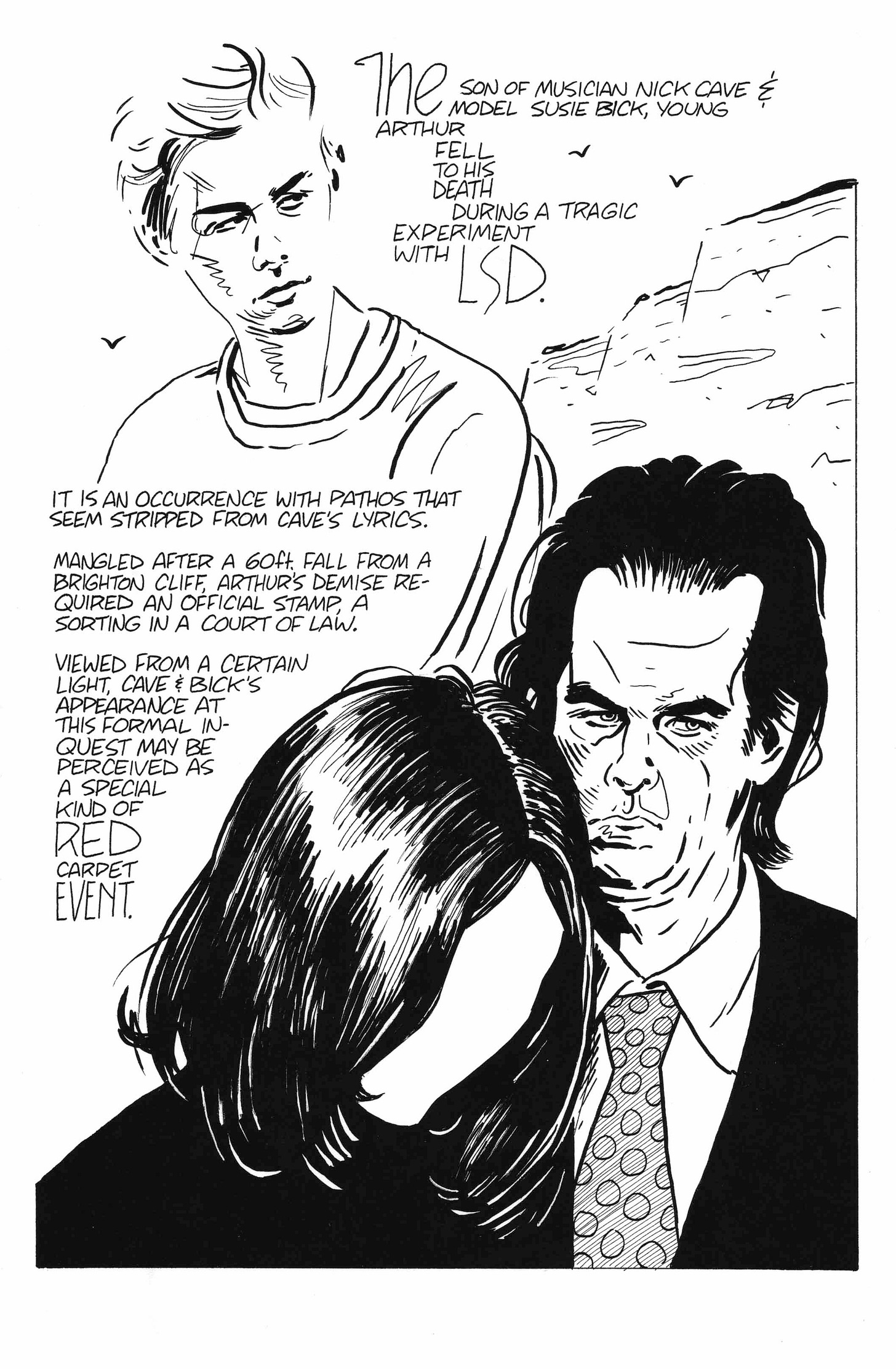

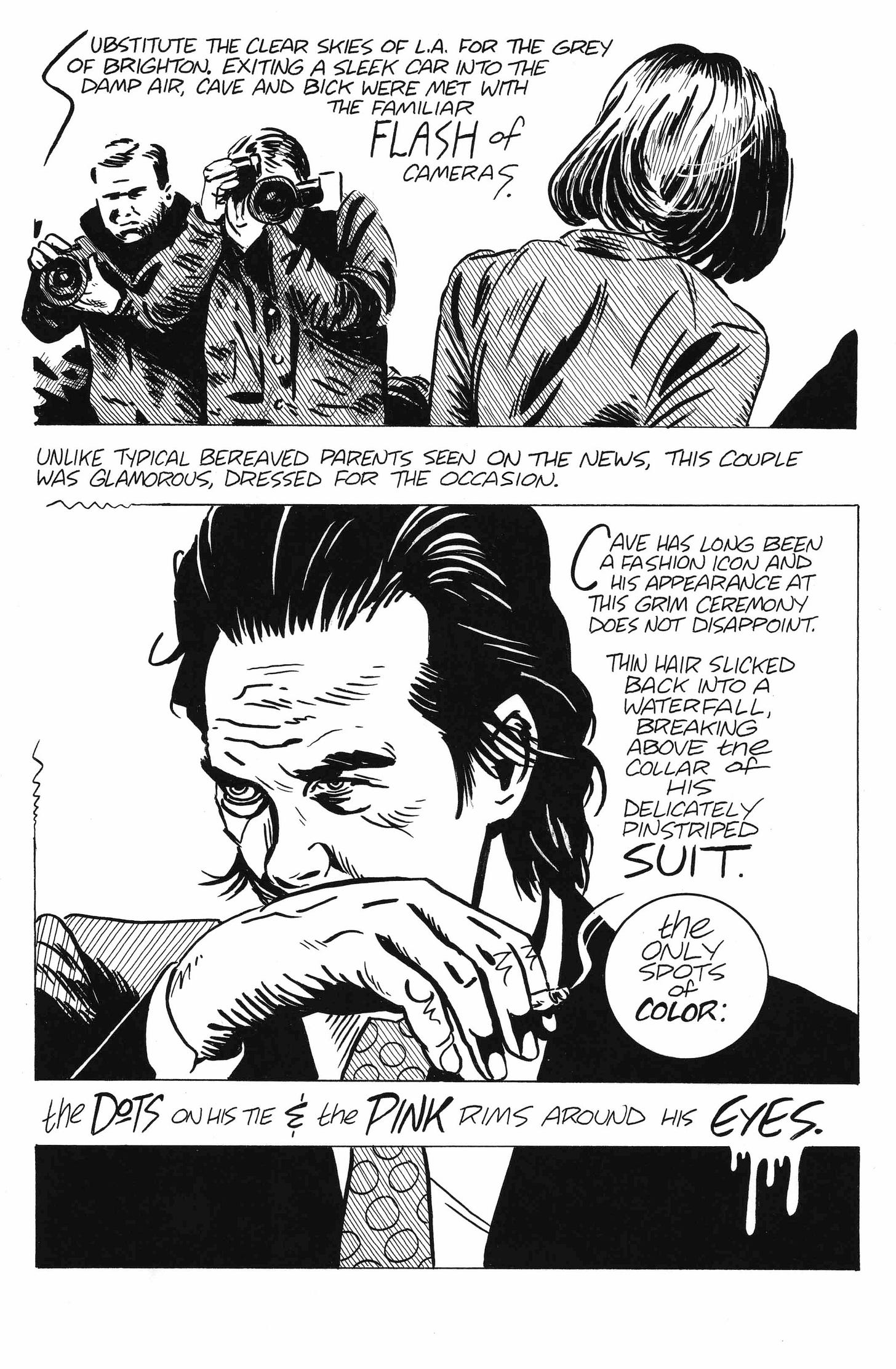

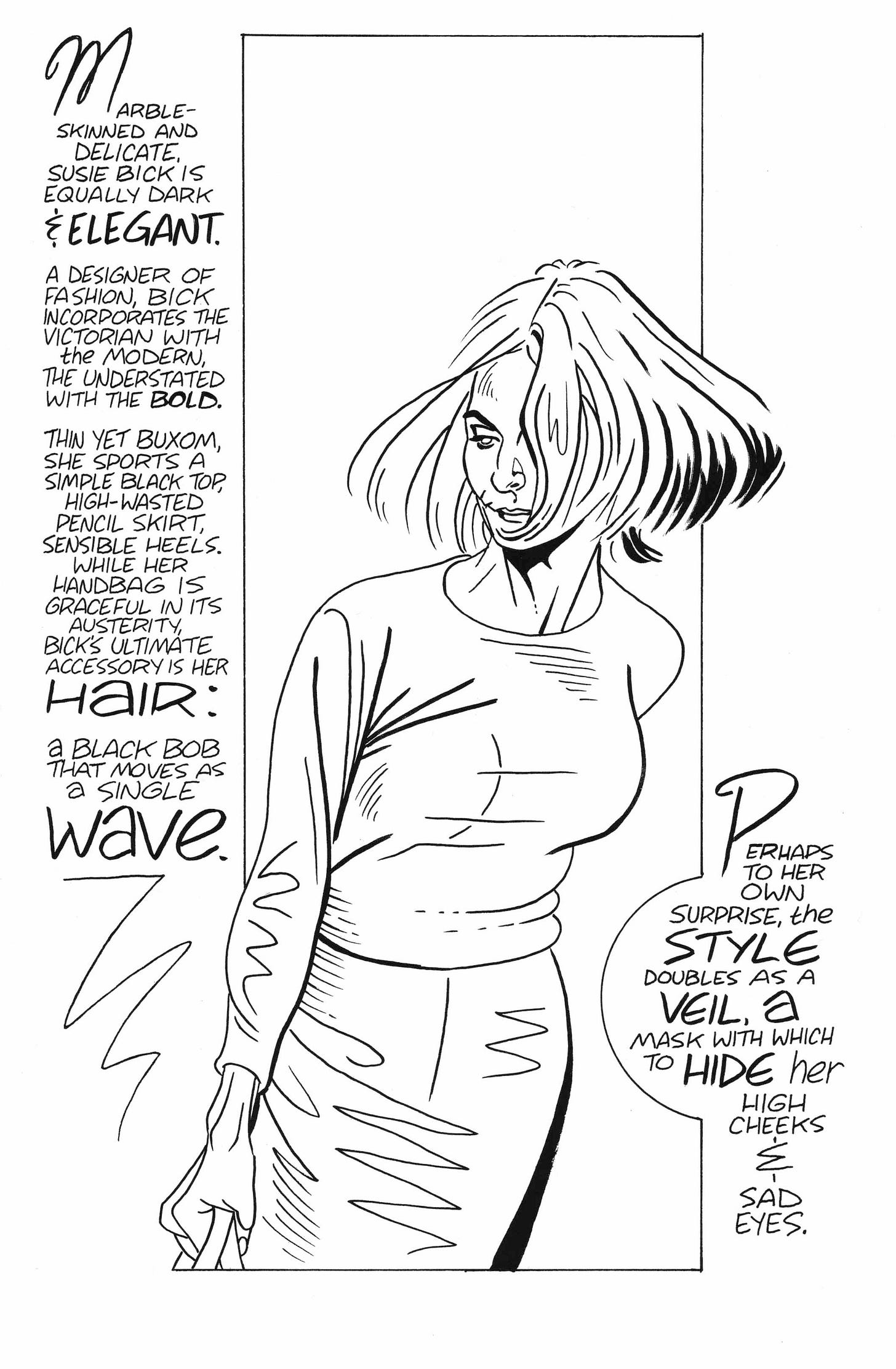

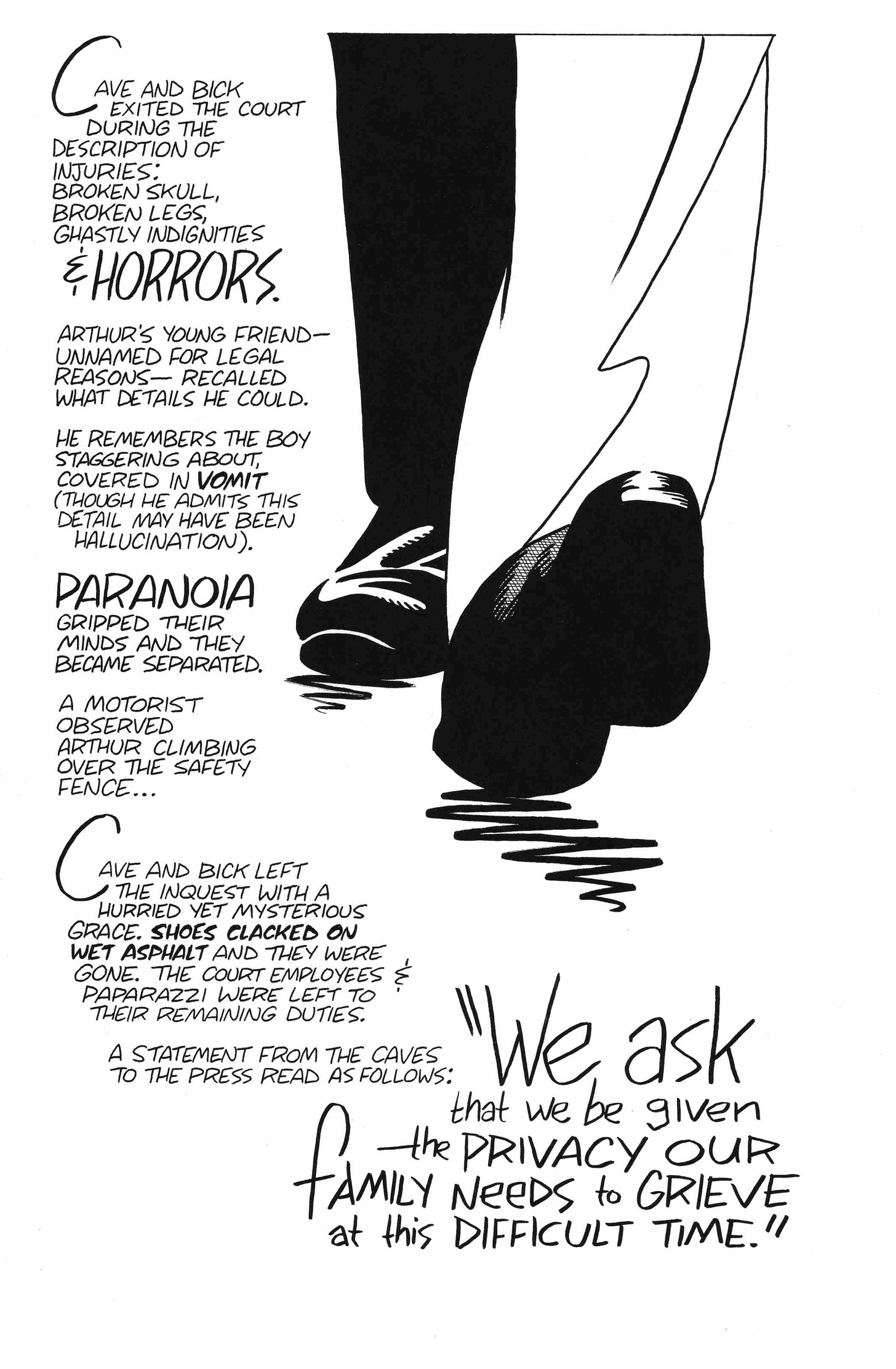

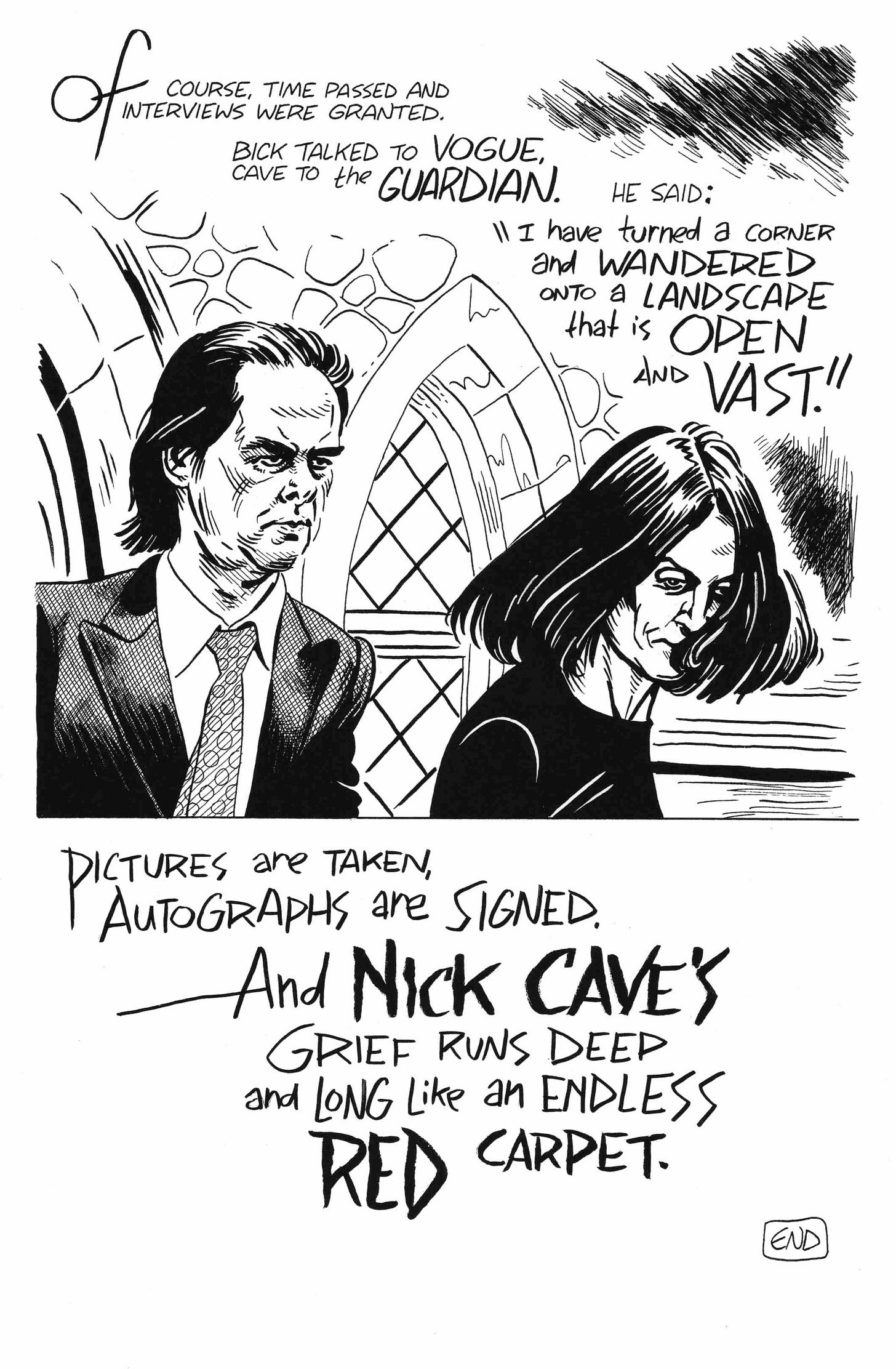

“A broad disease within punk and goth generally, the transition of the esoteric musical underground to Dad Rock, just like the Dad Rock of old, is predicated on incentivizing passive listening to these artists, skipping the lore entirely, latently afraid to let these bands fundamentally alter their beliefs about art, society, and spirituality. Just as there are Stones fans who don't know about Brian Jones, Nirvana fans who don't know about Steve Albini, or Pink Floyd fans who don't know about Syd Barrett (or, worse, don't care), so there are Nick Cave fans who don't know him beyond his accidental trauma-industry, Current 93 fans beyond the Huysmans Flip era and, spectrum-wide, that the progenitors of punk and goth were all listening to dub and reggae as much as glam. Take it from a former New Atheist who distanced himself from the esoteric aspects of these groups for so long because I thought it was all bullshit. A Sirius XM station is in order. XM 333.0: Godstars.”

—

“Now in my forties, ‘Dad Rock’ takes me to the musical context of the white suburban Dads of my childhood: The Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Paul Simon (with or without Garfunkel), and endless others. Most of my fellow children of the 80s and 90s could produce a similar inventory. These lists don’t include anything particularly interesting: always The Beatles, never The Kinks; always Led Zeppelin, never T. Rex. The importance of this music to a generation of Dads has been written about ad nauseam, as this music is a crucial aspect of the white Baby Boomer culture that has unflinchingly dominated western life for more than 60 years, claiming to have created a world of opportunity while dedicatedly eliminating a vast number of possibilities for finding happiness and comfort. Continually revisiting the hopeful but largely empty music of their youths allows Boomer Dads to continue to inhabit this world of opportunity that they claim to have created, but which only ever existed for them. In this way their dad rock provides these largely white and comfortable Boomer Dads with a place of strength and occluded perspective, a means for pretending that their imagined reality exists: put on Immigrant Song by Zep and have a rockin’ good time, but be sure to ignore that it was directly inspired by a trip to Iceland during which Led Zeppelin thoughtlessly thrusted across a civil service picket line so that some college kids wouldn’t miss their favorite band; buy another new reissue of your favorite Beatles album, ignoring the fact that your old ears can’t tell the difference anymore, if they ever could. This music allows Boomer Dads to set aside consequences and complex interrelations for a world where inchoate good intentions and looking out for yourself define a compassionate ethos.

The link between nostalgia and music is not, of course, limited to the Boomer Dad: people throughout the world and of most ages latch onto the music of their youth. More commonly, however, this nostalgia comes with self-awareness. While I enjoy Will Smith’s Men in Black and The Cardigans’ Lovefool, they don’t define who I am. Generation X isn’t self-defined by grunge, college rock and early hip-hop; and while many millennials do cry themselves to sleep, this is merely coincident with emo rock. The Dad Rock beloved by Boomer Dads has a firm generational association, but it also reinforces a deluded worldview. Perhaps the defining kernel of Dad Rock isn’t nostalgia (the emotional link to the music) but in the function that Dad Rock has in a life: the creation of an illusory world to be inhabited by the obsessed enthusiast. If this is the case, then additional iterations of Dad Rock can be found by searching for the illusory worlds that come from musical obsession rather than among obvious generational analogues.

Consider the aesthetically jagged music that emerged in the 70s and 80s: Throbbing Gristle, Nurse with Wound, Death in June, Einstürzende Neubauten, Coil, Current 93, and many others. These groups are classified using genre terms like noise, industrial, or experimental, often to the protests of the musicians themselves; I use them here for clarity. This music was created at a nexus of cultural disgust and artistic experimentation. These bands mostly originated in industrial cities that were quickly deteriorating: manufacturing jobs were rapidly lost to the automation and cheap overseas labor that swept in as post-war Fordism gave way to globalized neoliberalism. Simultaneously, as opportunity and middle class stability began to evaporate, popular culture became increasingly uniform, and nuclear fear was a constant undercurrent to daily life. As the 80s crested, the Anglosphere was dominated by Thatcher and Reagan rampant. In some cases, the creation and recording of this music began as an offshoot of extreme performance art: Genesis P-Orridge and Cosi Fanni Tutti first collaborated as part of COUM Transmissions, offering live performances rife with violent and sexual imagery, before becoming Throbbing Gristle. Groups also emerged from pre-existing musical scenes: the punk band Crisis became Death in June. Later groups share a lineage with earlier ones. David Tibet’s Current 93 was closely aligned with both Death in June and Psychic TV, a collective that emerged from the ashes of Throbbing Gristle. This music is typically concerned with achieving a state of transgression via dissonance, inspired by various writers and visual artists, including pseudo-contemporaries such as JG Ballard and William Burroughs; the historically controversial, such as the Marquis de Sade or Aleister Crowley; and surrealists and Dadaists, including Max Ernst.

Early noise or industrial music is difficult for the listener. Both recordings and live performances present constantly shifting collages of harsh and clashing sounds. This music was not created to be enjoyed. Instead, industrial noise is designed to include the listener in the nihilistic impulses that inspired its creation. For a futureless child of newly unemployed working class parents, attending a Throbbing Gristle or Nurse with Wound performance, or putting on one of their records, provided an emotional release and allowed a specific worldview: ‘the world is an uncomfortable mess that doesn’t accommodate me, and this music captures my anger and the failure of my society to make a place for me.’ This is not music that inspires a nostalgic impulse–most people don’t want to be reminded of a hell they used to inhabit, or, in many cases, still do.

Despite the clear provenance of these bands and the cultural circumstances from which they emerged, the albums of this period have an audience more than forty years later. I first learned about these groups in the early years of the 00s, when I was in my late teens and early twenties. The culture of the music geek had begun a shift to online spaces, and sites such as Pitchfork and Tiny Mix Tapes became tastemakers. These sites began by offering reviews of new music, but soon branched out into creating lengthy decade- or genre-based lists of ‘best albums.’ I excitedly reviewed these lists as they were published, taking note of the albums I needed to find at the record store where I worked part time. In ‘The 100 Best Albums of the 1970s,’ Brandon Stosuy bizarrely describes Throbbing Gristle’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats as a timeless dance record (it isn’t). Coil created ‘bleak meditations’ and Nurse With Wound’s Homotopy to Marie was a ‘twisted masterpiece.’ These lists manufactured a new audience for music that had confirmed the lived experience of hopelessness in a specific time and place. This new audience, of which I was a member, was largely college-aged, suburban, and white, living a privileged existence and focused on a hobby that allowed for obsessive collecting while requiring nothing aside from money to spend, and a willingness to scour taste making websites and record bins. We listened to these albums and pretended to like them, pretended to know what they were trying to communicate. We jockeyed with each other to have and enjoy something more obscure; and to use language that had virtually no meaning to describe the sounds we heard. How obscure could any of this music be, really, when we were all looking at the same websites?

Over the past twenty years, interest in this music has remained steady. As some of these obsessive collectors turn away from a youthful pastime, new collectors join them. Many of the collectors my own age are now parents—Dads, mostly—who retain this obsession as an escape. They come home from their jobs to the obligations of a moneyed and suburban family life. On the weekend and in the late evening, they take a few minutes to put on their headphones and slide a record out of its sleeve, feeling the relief of superiority. Perhaps the record is one of the original 5000 copies of 20 Jazz Funk Greats (only $300 on discogs, mint condition). Not only do these collectors accrue enviable and valuable symbols imbued with their importance, they can also pretend to like music that has no connection to their lived experience and that garners no impulse to explore the lived experience of others. Older now, they can reclaim a small bit of youthful vitality through these early industrial records. This disaffected and aurally discordant music, like the music of the Boomer Dad, allows listeners to channel obsession into an illusory world—a world where the records you own validate who you are by indicating that you have good taste, carefully cultivated.

Music becomes Dad Rock—this is obvious from the appropriation of industrial music as a symbol of taste, but is also true of the classic rock that obsesses the Boomer Dad, which initiated a pulsing undercurrent of restless youth into the rites of consumerism before becoming a link to the past. Dad Rock is not the music itself, but a mode of engaging with music: the Dad is anyone who employs musical obsession to hide away, engaging with subcultures constructed around class and privilege to build a static and guilt-free space of escape. With this pattern in mind, other iterations of Dad Rock appear, shattering the gender line of the boomer ur-Dads who inspired the term: a Dad can hide under any rock. Phish and The Grateful Dead have spun the worlds of aphishionados and deadheads; EDM lovers travel the festival circuit; and enthusiasts of classical music often live in a distinct airy and cultured world, above the rest of us. Dads and their Dad Rock, all.”

—

art by Dan Heyer ()

comic by Aaron Lange ()

There is so much overwrought reconstructive criticism in this article, it beggars belief. Peak high dimensional venn diagramming at its finest. I love it. Don’t ever change.

Takes me back to being in college in Iowa in 2007 and everyone was creaming their pants over liars and xiu xiu