English

Inferior to Chinese and French?

“As a monoglot barbarian in the central backlands of the American empire, I’m unable to comment on the strengths and weaknesses of English from a comparative or outside angle. Hell if I know how English sings and signals relative to other languages. But I do qualify myself to intuit this—now that one tongue lies heavy across the whole globe, my native language has made aliens of us all. English is the terminological machine of vast and interlocking and highly irritating industries, warping everyday speech into a pseudo-neutral slobfest, draining the color and smashing the tenor of local vocal patterns and robbing precision from analytical fields. Corporate speak, therapy language, and realist fiction form a triste triptych of linguistic and spiritual abomination, arising not so much sui generis but as yet another bastard child of a tirelessly rutting American Genghis Con.

The trouble with English these days is that it pours out of everyone as an artless affectation, a pretense without wit or charm; it has become as streamlined, disposable, and poisonous as any corporate product or government issuance. And I have no problem with pure adornment; but the decorations of the language these days are less than baroque or rococo, far from fine, and more like assembly line lawn ornaments, nursing home rhymes as political slogans, placards and flags of brainless affiliation.

It seems to me that English can do just about anything; yet so many people use it so clumsily to do as little as possible, and this they deem concision, utility, and even style. The mongrel origins of the language give it incredible malleability; its deep reservoir of synonyms, suffixes, prefixes, and borrowed phrases could inspire wild tinkerings and delicate shadings and complex associative plays; its grammatical riotousness and chaotic spelling could generate real out there utterances; what tends to happen is that invention is hitched to the charlatanical impulses of always working oaficials on mental leave, while the ostensible artists have taken to writing under rules so tight assed that verbal craftsmen fart at the pitch of a dog whistle.

English is upside down and inside out, and not in a fun Lewis Carroll or Oscar Wilde way, but like a mind control torture amusement park ride. The scientists and functionaries lie like there’s no right now and the artists strain to tell a belabored and dull truth. Where discourse needs specificity, there it is fogged with vagueness; where art needs flexibility, there it is straightjacketed by institutionalized nutjobs. Between corporate mendacity and artistic sincerity, there’s almost no room for fresh phrases.”

—Caleb Caudell

“Are we tired of English yet? Is this squinting at Latinate complexity through cheap NHS glasses to a chorus of Germanic pig grunts still rewarding? The earliest written documents of ‘creative expression’ in the language are vulgarly provincial in the extreme and compare poorly—we could truthfully say execrably—with their counterparts in the rest of the world. How exactly is Cædmon’s Hymn supposed to stand up against the achievements of Tang Dynasty poets like Li Bai and Du Fu or, in the West, the Latin tradition? When Catullus has set a precedent, is it too much to expect it to be acknowledged? From the available evidence, it was in fact too much for the inhabitants of the British Isles, those milk-skinned cavemen saddled with a language of inept concrete nouns and thudding verbs. Their attempts to import the metaphysical abstractions of what was by then reasonably late stage Christianity into a painfully limited vocabulary produced alarmingly alliterative results that have mostly been shielded from honest criticism due to their status as ‘historical documents.’

Apart from the sole remaining utterance of Cædmon, an illiterate shepherd whose superhero-style backstory (divine voices in the night blessing him with the power of poetry) makes us suspect that the Venerable Bede invented him as an excuse to pass off his own verse—in the manner of the later Macpherson with Ossian, the nonexistent Celtic bard whose hoary heroics inspired a credulous Napoleon—we’re thinking of something like ‘The Dream of the Rood,’ another unintentionally comedic pileup of Saxon syllables in which the Cross of Calvary expresses a tender lament for the redemptive agent nailed to it (the sexual undertones here can certainly inspire speculation), and, of course, BEOWULF—which, improbably, was made into a Hollywood film as late as 2007, and which stands as the best among its weak competition (never mind that direct engagement with its language involves harming one’s mouth with consonant-heavy Germanic palate shredders; it’s a bit like eating an expired box of Cap’n Crunch: the oral damage sustained overwhelms the buzz of any sugary ‘action’ content). It’s worth noting here that the latter poem received a reputation boost thanks to the Hobbit-chronicling Professor Tolkien, at whose feet we can lay blame for the modern Fantasy genre; we suspect that even the anonymous Beowulf poet would have been distressed to see where his influence has led.

With such shoddy foundations, it really would have taken six or seven further Norman Conquests to Francophonify English into basic usability. Shakespeare, perhaps appalled at the poverty of the linguistic resources available to him, was forced into the wholesale invention of much of the vocabulary we use today, and in his parodies of ‘heroic, manly verse’ (‘whereat, with blade—with bloody blameful blade—he bravely broach’d his boiling bloody breast’) and self-critical plays-within-plays we can sense something of his anxiety at having to strain against the limitations of his native tongue.

Almost everything interesting in English is extremely recent and extremely dependent on French sources. Pound and Eliot’s Modernism owes its ‘innovations’ to Laforgue, Nerval, Baudelaire and the rest of the groundbreaking 19th century crew, as well as what quasi-plagiaristic use they could make of Chinese poetry. It’s notable here that even Pound’s third-hand ‘translations’ of Li Bai came as a revelation; Chinese poetic art from more than a millennium earlier is clearly capable of holding its own even when put through such filters, unlike the previously mentioned Old English verse.

Contemporary Englishmen and Englishwomen (we prefer the term ‘Anglesses’ for the latter, as in ‘Arthur caressed the angles of the Angless’) are of course merely human and their merits are so dependent on the individual as to make general statements meaningless. Against all odds, there is something to be said for local English dishes and even the simple staples of pub food, although reports suggest these have deteriorated in recent years…but even the lowest quality fish and chips is preferable to reading most English writing before about 1850. There is a prevailing sense that English itself was never very supple, and needed to pillage the rest of the world’s linguistic resources: a pirate language for a pirate nation.

As for Paul Kingsnorth, the perpetrator of novelistic attempts to revive a mangled pseudo-Old English, he must do a penance by changing his name to Paul Roi du Nord and writing his next novel from the sainted perspective of the Norman invaders.”

—Justin Isis

“Shakespeare, when you read him you feel an insane and unique feeling of tension, halfway between estranged fulfilment and the bittersweet circularity of hysteria, don’t get me wrong, I love hysteria, I’m hysterical right now, I’m not arguing against the hystericisation of the English language, there’s no reason to: a language can only be hystericised once, and it’s already been done, and it’s good, perhaps, that we have been given this strange alternative to becoming French. The problem is: what happens to a language after it’s been hystericised to perfection? As Elizabeth Barrett Browning argues:

‘There Shakespeare, on whose forehead climb

The crowns o’ the world; oh, eyes sublime

With tears and laughter for all time!’

Yes, what to do about this hideous unending grift-stream of self-exoticising Englishmen, what to do with these plum-bodied and plum-minded world-dampeners, these columnists, for whom Shakespeare functions not only as laugh-track but as cry-track?

Nothing; beyond ‘the English language,’ there is no problem. Shakespeare fails because, firstly, he is talking to someone, and secondly, because he is talking to the English. His language bends by ulterior geometries; he is relevant not because he is eternal but he is eternal because he is relevant. Shakespeare’s dream of a thought ‘without any gaps’ is nothing but the dream of a thought that is not a thought, a thought that cancels itself in its urge to transparency.

C.f., Cervantes. On what basis do the characters of Don Quixote enjoy themselves (and they do nothing else)? Because, firstly, the novel, qua form, is inoculated against transparency (the backside of perfection). At the last possible moment, the form has its way with the content or the content has its way with the form. The window is open. The air moves, the water moves. If the novel was not the invention of silence, it was at least present for its birth. In Don Quixote, it offered a nonchalant hand of friendship to silence’s quickening.”

—Philip Traylen

“All Old English and nearly all Middle English works produced hatred and weariness in everybody who studied them. The former carried the redoubled impediment of having Tolkien, incoherent and often inaudible, lecturing on it. Nobody had a good word to say for Beowulf, ‘The Wanderer,’ ‘The Dream of the Rood,’ Cynewulf and Cyneheard. Philip [Larkin] had less than none. If ever a man spoke for his generation it was when, mentioning some piece of what he called in a letter to me ‘ape’s bumfodder’, he said, ‘I can just about stand learning the filthy lingo it’s written in. What gets me down is being expected to admire the bloody stuff.’

So far, as I say, so standard, but he would have commanded less general support for his equally hard line on Middle English literature, in which others could find a few admirable or at least tolerable bits, mostly by Chaucer. When it came to works in Modern (post-1500) English, he was on his own.

I have no recollection of ever hearing Philip admit to having enjoyed, or again to be ready to tolerate, any author or book he studied, with the possible exception of Shakespeare.”

—Kingsley Amis

“I am given to understand that Philip Larkin took a dim view of Old English literature, and even, as he put it, the ‘filthy lingo’ in which it was written. I am not exactly surprised at this. I am an admirer of Larkin’s poetry, fiction and letters, but his taste is as narrow as the typical British palate is when it comes to food (Morrissey is a good example here in many ways. In an interview with Far Out magazine, he stated: ‘I can’t eat anything with any flavour. I’ve never had a curry, or coffee, or garlic.’). If I am not surprised, however, I do find a certain oddness in this disposition of Larkin’s. His short poem ‘Modesties’ seems to express a deep fondness for the thought and language of what we might call common folk:

‘Words as plain as hen-birds’ wings

Do not lie,

Do not over-broider things -

Are too shy.

Thoughts that shuffle round like pence

Through each reign,

Wear down to their simplest sense

Yet remain.’

What kind of words and thoughts are these? What comes to mind for me is the way that both Larkin and Morrissey use familiar idioms with a new context to bring out in them strange echoes of feeling that seem to belong at the same time to us personally as individuals and to the older, unwritten history of countless forgotten lives before us. Think, for instance, of the poem ‘The Old Fools.’ The title works because it uses a known idiom with a new meaning, but it is the resonance of an enigmatic familiarity that first catches us. Morrissey does the same with titles such as ‘Handsome Devil’ or ‘Hand in Glove.’ Such phrases represent thoughts that belong to no one and everyone, passed down, as Larkin says, ‘through each reign.’ From ‘The Hand that Rocks the Cradle,’ by The Smiths, we have the wonderful line, ‘Oh, see how words as old as sin fit me like a glove.’ One feels the weight of one’s ghostly unknown ancestors at one’s shoulders. One feels the atavism of language itself, as if in using the language one mixes up one’s memories with those of innumerable dead.

Does it need pointing out that much of this particular mode of writing makes use of the Anglo-Saxon component of Modern English? The words ‘old’ and ‘fools,’ for instance, both come from the Old English, as do ‘hand’ and ‘glove.’ They are words, as Larkin would have it, ‘as plain as hen-birds’ wings,’ and yet they are haunted, too, by the ghosts of generations of those who lived and died and are forgotten but spoke these words before and passed them down to us. I feel very much the ghostliness of ‘hand.’ Or, for that matter, the ghostliness of ‘ghost,’ which is also from the Old English. It turns out that ‘word’ and ‘hen’ and ‘bird’ are also from the old, Anglo-Saxon tongue. Well, it will be tedious, perhaps, simply to list words like this, though, personally, I quite enjoy it. Perhaps I can add before passing on, at least, that there are some surprising words with Anglo-Saxon roots. For instance: ‘hovercraft.’ This does not seem entirely inappropriate: an amphibious vehicle in some ways ‘futuristic’ and in others as quaint-seeming as the hot-air balloon.

My own palate is not as limited as Morrissey’s or as Larkin’s. I enjoy the use of English in various modes. But I value that mode exemplified by the plain but vaguely haunted idiomatic diction I have sketched briefly above because it makes especial use of those things that are unique to English, apart from its eclecticism, which is, after all, perhaps not that unique. I am also saddened by a sense that speakers of English are losing touch with such plain and ghostly idioms. When was the last time you heard someone say, ‘The old fools!’? When, indeed, was the last time you heard anyone say anything in English that gave you a faint shudder, a mix of cold and warmth, as one might experience when stepping out of the dark and misty night into the firelight of the mead hall, and made you remember that the language you speak was for centuries on the tongues of those who lived and died before you? I fear that our idioms now come from corporations and bureaucracies, from committees of entertainment and academia and technology, and not from the untended weeds of ordinary life.

One of my favourite pieces of writing is something under the title of ‘A Grant of Land at Crediton,’ which I know in a translation in the Oxford World’s Classics’ The Anglo-Saxon World: An Anthology. It is not a poem or tale, but a legal document in which King Aethelheard bestows upon Forthhere, a bishop, land for the building of a monastery. It helps that the patch of land in question is in the general part of the world in which I grew up, so that I feel towards it almost as one might feel towards an in-joke one shares with a friend. The text runs to two pages and most of it, apart from formalities at beginning and end, is taken up with describing the boundaries of the land in exact and, we might say, parochial detail. ‘Now these are the lands,’ it begins. ‘First from the Creedy bridge to the highway, along the highway to the plough ford on the Exe, then along the Exe until the grassy islets, from the grassy islets onto the boundary ridge, from the boundary ridge to Luha’s tree, from Luha’s tree to the enclosure gate, from the enclosure gate to Dodda’s ridge, from Dodda’s ridge to Grendel’s pit, from Grendel’s pit to the ivy grove…’ And so it goes on, having a cumulative effect that is poetic and absurd and, to me, also touching and oddly sublime.

What is literature about? On the one hand, as Samuel Johnson wrote in The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia, the poet ‘does not count the lily’s stripes.’ In other words, the writer is more interested in the general type of a thing than the specific instance. On the other hand, in comparison to the philosopher, the poet, or writer of fiction, is, indeed, interested in what is sensual and specific and earthly. We, as writers, are caught between these two poles, and there is something fascinating in going first in one direction and then the other and getting a feel for the contrasts, and the meaning of them. For me, ‘A Grant of Land at Crediton’ is close to the extreme specific end of the spectrum. Here we have an instance of pure specification of a portion of time-and-space, of locality, all ringed about with odd names, suddenly sprouting a crab-apple tree here for no good reason, or missing its footing there and splashing into a ‘cress pool.’ Language is not only universals. It is also gnarled with the marks of its time-and-space origins. For me, the English language comes from somewhere like this, like this Crediton, from a few acres of soil and tree and grass that, for some reason, will haunt me throughout all time and space, and even should I be transported to distant stars. Yes, it will haunt me forever, this miserable and tender patch of earth.”

—Quentin S. Crisp

“The King James Bible contains some great lines. This is a good one, I think: ‘I shall have peace, though I walk in the imagination of mine heart, to add drunkenness to thirst’ (Deuteronomy 29:19). And this is a rather poetic description of menstruation: ‘And if any man lie with her at all, and her flowers be upon him, he shall be unclean seven days’ (Leviticus 15:24).

‘English’ is the King James Version (1611), William Shakespeare (1564-1616), and some earlier things, like Chaucer (c. 1343-1400) and Beowulf (maybe 700-1000); and there’s Milton and Blake and some late arrivals on the scene, like Dickens and Austen. It doesn’t matter if you’ve read any of them. If you are English, or speak English, or live somewhere where English is spoken, you’ve sort of imbibed these somehow, or know that you were once meant to, or will in retirement (optimistically).

We are supposed to know, or think, or believe, that ‘English’ is a kind of lumbering, powerful, furry and slightly rotting creature made up of older and newer parts. Like a tree covered in moss that stumbles towards us saying all at once: ‘Beowulf wæs breme blæd wide sprang, Scyldes eafera Scedelandum in’ and ‘All the world’s a stage’ and ‘There is nothing new under the sun.’

English is blunt and wise and ancient and empirical like a dagger. It is the language of law and contracts; and of being a pissy, sardonic, sarcastic bastard. It is effete and cynical, triple-edged, and quite gay, even or especially when used by women. It is the language of money. It sounds like office chairs being stacked and awkward inquiries into how the other fares. Awkward because the language itself is embarrassed in its very speaking. Codified throat-clearing. It is cunning.

I liked the English spoken by my Grandmother, who spoke in idioms and did not write, having left school young to work on a farm. She would say things about the sky and about birds and they would refer to or mean something mysterious and a bit misty. She often said that things were ‘disgusting,’ but her morality seemed to be that of an eggshell, blue and fragile and natural rather than institutional. I could not explain to her the value of a PhD because every time I tried to explain what it was I did, she didn’t believe me. In the end I told her ‘I read and write about books for a man,’ and that was alright, though still not a proper job.

I think Philip Larkin probably ended English in the middle of the 20th century. Look:

‘I listen to money singing. It’s like looking down

From long french windows at a provincial town,

The slums, the canal, the churches ornate and mad

In the evening sun. It is intensely sad.’

There is no English after Larkin. He could see the great international machine coming and decided to bash its head in with a spade and bury it across the road, as my father once did with a mole that was leaving piles of earth in the garden.

English is a mournful but not passionate language. It lacks sex and thus is perfect for the Internet. We can make love at a distance in English. English is closest to numbers than any other language, which is why it is the language of angels.”

—Nina Power

“I’ve long felt that one of the chief flaws of the English character (well, aside from their fondness for fox hunting, their pathetically short-lived TV sitcoms, and their adoption of a watered-down version of the Lutheran heresy) is their general philistinism, which is very ironic, when you consider all of the truly great artists/works of art that have been produced from the ‘sceptered isle’ over the many centuries. Certainly any country that has bestowed upon the world the two Williams (Shakespeare and Blake), post-punk/Goth music, AND Mr. Bean is a country capable of great aesthetic range. And yet often it seems as if the English are painfully embarrassed by the very things which make them great. Nowhere is this more evident than in the comportment of their so-called music journalists, especially from the 1970s to the 1990s, and their vituperative disdain for progressive rock, much Goth/post-punk, dark synth pop, or indeed nearly any musical act that had even the slightest whiff of artiness, theatricality or pretension (it would be pointless to identify most of them here, as the names of these self-anointed kingmakers have long since faded into oblivion, but Melody Maker’s Steve Sutherland is a good reference point).

In his monolithic study devoted to the musical career of Emerson, Lake & Palmer (The Endless Enigma, 2006), Edward Macan traces (among a great many other things) the evolution of shifting ideological mores amongst British music journalists in the 1970s, and how some time around 1973-1974 (and reaching its apotheosis in 1976), the then-prevalent ideology of utopian synthesism was almost completely overshadowed by what Macan refers to as the ‘Blues Orthodoxy’ (though this term itself was first employed in the texts of Bill Martin). Essentially, and in much the same way that the Anglo-Saxons were defeated by William the Conqueror in the Norman Conquest of 1066, British music journalism was infected by the cynical, pseudo-hipster Beat Generation/Gonzo-inspired rock criticism incubating ‘across the pond’ in America, as pioneered by the vile Satanic anti-Trinity of Dave Marsh (Rolling Stone), Lester Bangs (Creem), and Robert Christgau (Village Voice). The music championed by these boorish charlatans, these flabby mustachioed polemicists in their ill-fitting T-shirts, was only aesthetically pure if it fell within the narrowest of parameters: it needed to be populist, from the oppressed/working classes, authentic (ironically, in this regard they had common ground with the utopian syntheists), commonplace, and somewhat anti-intellectual…what it could NOT be was arty, elitist, or pretentious. Most of all, it had to be ‘gutter pure,’ a direct descendant of either rhythm & blues or ‘Black’ music in general. This is one of the reasons why progressive rock was generally shunned by both American and British music journalists: because it was somehow seen as contaminating what Bangs called the ‘gutter purity’ of rock & roll with alien Modernist/European/‘White’ musical strains.

What this all boils down to is that these critics and music journalists were advocating what Macan classified in his book as a ‘vulgar, debased Romantic primitivism.’ Which, in its own attempt to be seen as racially progressive, was actually kind of racist in and of itself, as cultists of the Blues Orthodoxy sought to impose their own White Romantic Primitivist vision on Black American music, recasting the Black bluesmen and jazz musicians as ‘noble savages’ naturally born with music in their blood (in this line of thought, they were somewhat of the mentality of many White basketball fans of the 60s through the 80s, who tended to see Black professional basketball players as lazy but born with God-given athletic talent, in contrast to White players, who supposedly had to work hard to develop their skills). As proof of how wrongheaded a notion this was, one need only to look at, say, the bebop pioneers of Dizzy Gillespie, Kenny Clarke, Charlie Christian, Charlie Parker, and Thelonious Monk, who spent countless hours experimenting and theorizing as to how they could move their own music away from the conservative diatonic harmony of swing and more towards the complex avant-garde harmony of chromaticism, incorporating dissonance, fragmentation, and tritone substitutions. Ironically, many of these early pioneers of Black musical forms were more in sympathy with the ideology of the utopian syntheists, in that they weren’t adverse to taking inspiration from other musical modes of expression outside of their own cultural/ethnic spheres (which would perhaps no doubt horrify the Blues Orthodoxists, who like the Nazi eugenicists wished for their music to remain ‘pure’): Dizzy famously loved Afro-Cuban jazz and incorporated elements of Latin jazz into his own East Coast jazz milieu, while Charlie Parker was inspired by the revolutionary Modernism of such European classical composers as Béla Bartók and Arnold Schoenberg.

One needs no greater proof of this ingrained nativist Anglophone philistinism than in gauging the reaction of the British music press (which ranged from an apathetic shrug at best to opprobrious invective at worst) when they were presented, nay, gifted, by their very own countrymen, mind, with that most inspiring Modernist creation of the 20th century, by which I mean, naturally, the armadillo/tank hybrid beast known as Tarkus. “But is it rhythm & blues based? Does it reflect the values of the working class? Oi, that’s too posh!” shrieked the unpolished limeys, in their collective indignation. Truly, the British concept of great art is as revolting as the general state of their national dentistry.”

—James Champagne

“Tired, England lays back and broods, thinking of himself. Once a domineering, barrel-chested, virile, and brutal father, he is now bent and shrunken. The great progenitor grows senile in his dotage. He rambles continuously about his great Culture and its greater Loss. He stinks; everyone can smell the rot.

Prolific, England is attended and emboldened by a scrum of oafish Large Adult Sons, chips off the old block, who alternately emasculate their dad and defer to him. Vulgar America, a Larger Adult Son than any of his brothers, is an exemplar of the family commission: devour and destroy in the name of honour and progress. Boys will be boys, after all. But don’t forget the other lads! Three sons live at home and bicker daily with old dad about their gradual loss of status and wealth: lairdly Scotland, sheepish Wales, and envious Ireland, a lonely twin. The other twin—defiant Éire—occupies the carriage house in a symbolic departure from the bosom of home: out there dad’s unceasing rants can safely be ignored, and Éire can dream of a different life. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand—nothing but acephalic and lumpen replicas of dear old dad. Occasionally, that disconcertingly musky cousin, South Africa, stops by, refusing to leave until everyone is boered [sic]. Privately, dad’s stiff upper lip sometimes trembles. After all, despite the challenges of being other than England, these boys have tried their best to bear the family burden through all the thankless years.”

—Siobhán M. La Grippe

“English. I should not speak this language as a native tongue, I wasn’t born on that grey island or any of its colonies, I don’t have any parents that were either. This is the basis of my ambivalence towards a nation and a language that was given to me but was never mine. More than a language, a system of values that whilst presenting itself as modernity’s default, was really a system of conquest that few could do anything but capitulate to.

The Anglophone world is guilty, guilty for its careless conquest of the world, and just like any narcissist it believes we all should share in its introspection. Examine the privilege of being part of an empire when there were few other options available. This scene happens more than you can imagine. It’s an open mic night in a bohemian part of an American or commonwealth country. The crowd is filled with the standard tripartite caste Anglophone system. At the top, the Brahmins, the landed gentry, there sit the original colonisers, the WASPs. Blue-eyed predators. They’re the most versed in the latest discourse of guilt. Like Victorian English aristocrats of yore, they don’t believe they are part of the cream of good society solely by birth, they believe it’s their own superior moral refinement that grants them this right. Their ability to both serve pain and receive delicious moral indignation in return. Today in this bohemian venue that serves up a broad, tasteful spectacle of multiculturalism across its stage, they’re also the ones most susceptible to guilt. They’re the ones who gain the strongest cathartic delight from being roasted by those below them; this catharsis sanctifies them and solidifies their belief in their superior moral faculties.

Right below them and beside them sits the first wave of immigration that followed their conquest. The ‘wogs.’ Not quite white but close enough, the honorary whites: Jewish, Greek, Italians, Irish, and the Slavic diaspora. Often complicit but really very very different just below the surface. They worship different iterations of the same god, not quite the voracious Protestant god and his spirit of rapacious colonial capitalism but compatible enough to become wealthy and prosperous living under his aegis. The Irish became white, became the cops of America, Italians built Vegas, built an easily consumable global culture and soon became an indivisible hybrid Anglo-American alloy, unrecognisable in their origin country. Their relationship to colonial guilt is complex, they’re true immigrants. I’ve been paying attention. They have complex stories, histories, places, left behind. Their culpability is complex. Like the Scottish with the first British colony, Ireland, they perhaps didn’t directly do the conquering but they benefitted immensely from it; this tier is ‘white enough.’ It is a valid question to ask, if settler-colonists invite others whom they consider less different than to come over to enjoy the spoils, do they share the same guilt? I know enough about this caste to know that non-Protestant Christians know when not to ask tough questions, unlike the erstwhile Protestants who’ve made radical candour their mantra.

The lowest caste is the Global South. South America, Africa, and the evergreen trendiness of the Middle East. Someone of this caste is on the stage and they’re performing the indignant subaltern well. Howling it. The Brahmins are lapping it up, they’ve perfected the sadomasochistic arts, giving and receiving pain is the most elevated of pleasures they entertain. The Cenobite sergeants of the world delight in this public roast. Yes, we did horrible unspeakable things to your people and you’re right to hate and revile us for it, and please yes do continue to tell us how evil we’ve been. The middle class wog tier demur to the top; they’ve gotten wealthy beyond belief by following the spirit of Protestant capitalism to this remote place. As for guilt, they’ll feign it if they’re smart. They’re mere witnesses to a master-slave dialectic locked in centuries ago, but they’ve paid a blood price for admission to this spectacle of pain. They gave up much of their original culture and language for a seat at this table, this global BDSM dungeon taking place right here tonight, and they don’t know how to think in any other language but English.

History advances generationally. Are kids responsible for the sins of their parents? Can immigrants ever return to their home cultures and recover what they lost? English is a remarkable language, a cosmopolitan language, able to express modern affects, complex and refined for the information age beyond anything that the old tongues could do. The only way forward is through. The near future is English, there’s no other option. Everything else is regression, cottagecore, and nostalgia. We’re all modern Cenobites now, refined in the English art of giving and receiving pain. Pain breaks the rhythm, breaks the rhythm. The 19th and 20th centuries were about sadism, now the tide has turned towards masochism: whoever has had the most pain inflicted upon them wins ascension into secular sainthood. Whoever is able to bear the most guilt wins the moral war of the English gentry. So charming, so cruel, so self-aware.”

—Ivan Niccolai (Notes from the periphery)

“English is violence and is the most violent language. Speaking English is like speaking cancer, plastic, algae or methane. Mistake not, were it not English it would’ve been another language—perhaps Norse, uncorrupted French, Dutch—but this type of speculation is for the annals of science fiction. There should be no endangered languages in the age of the Internet, but here we are. Gaelic, at least, is the linguistic giant panda. A pronounced regret of this monolinguist is that his first and only language is English. At times he wants to be alienated from Anglophonics altogether.”

—Colby Smith // YUUGENPRAXIS

“What do they know of English that only the English know? The most beautiful language, from a sonorific perspective, regardless of the meaning of the words, is Hawaiian, with its airy vowels and few smooth consonants. French, Italian and Spanish all have their place in the history of aural beauty but Hawaiian stands above all. My own mother tongue, which is probably also yours, English, with its chaos of guttural stops and dysphonic cognates, has never won a linguistic beauty pageant. And it continues to suffer daily humiliations because of its status as the ‘lingua franca’ of so-called ‘global business,’ the so-called ‘Internet,’ extra so-called ‘‘‘‘AI’’’’ and desperate people on the make in every corner of the globe. The British empire was defeated (mostly by itself) but left a cruel revenge on the world. The world has responded by forcing loan words into English at an astonishing clip. Or has English maliciously appropriated foreign words for its own purposes? It’s gotten to the point where we don’t know who is trapped inside with whom. I know Anglo-Saxon revanchists who try to excise Latinates from their speech, but usually end up producing compound German monstrosities that would have enraged Mark Twain.

I have 11th grade Latin, I can get by as a tourist in Mexico, and I have the Lord’s Prayer in Anglo-Saxon memorised, but as a monoglot, like a parent of an only child, I can’t help but love English, while concealing deep in my heart knowledge of its flaws. It’s difficult to separate the flaws of a language from the flaws of its speakers. To ask me to do it would be like asking a fish to describe the flaws of water. Indeed, What Is Water? Oh, So Deep.

While the use and abuse of English expands at an exponential rate, its scope becomes narrower and narrower, its potentialities are neutered, its complexities and glamour destroyed by an unholy alliance of grammarians, utilitarians, advertisers, autocorrectors and scammers, no other language is available to me, and probably to you. We must treat it as well as we can, love it despite its flaws, for love can have no meaning if its object be perfect. Aloha hoku ohana.”

—Lucas Smith

“Wild that there’s still some mfs out here tryna be Shakespeare scholars, talkin bout ‘Shakespeare was the first gangsta rapper’, or ‘What Shakespeare can teach us about being a mollusc in the post-Anthropocene’ or something.

Stop the Cap!”

—Udith Dematagoda

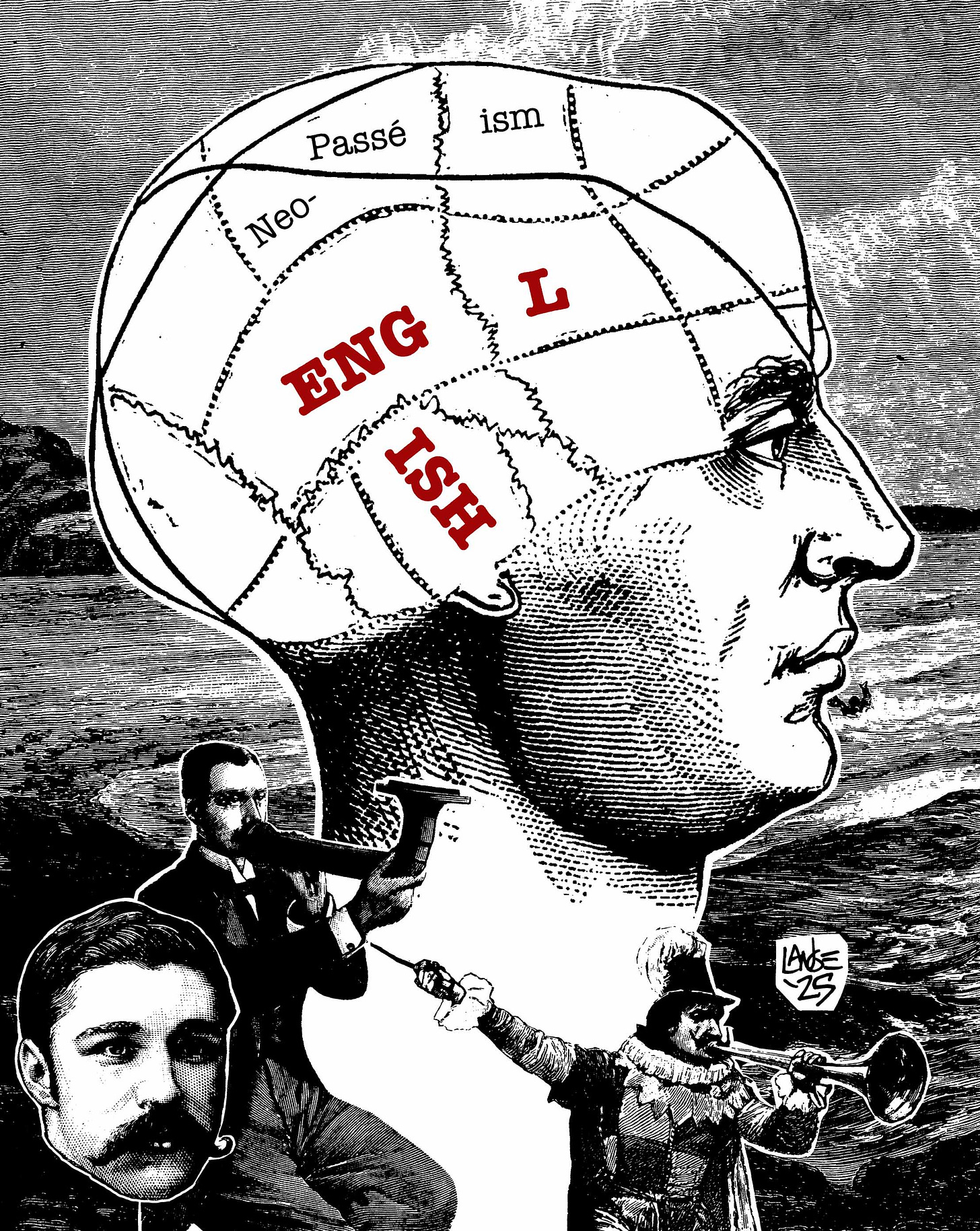

art by Aaron Lange

I learned to love in Spanish and count in English. French came to me out of spite and Italian on a whim. Portuguese I absorbed supine. And when I was in recovery, I lost everything but the basics in the two languages I learned from birth (without the ability to count in any.) Music died. The fury of that loss I could only express in English. And I have only begged for forgiveness in Mandarin (of all things!) The language of my revenge is the sound of an atabal. But here I am again writing all of this, as the sun rises, in plain English.

Best [Old English] post [Latin -> OE/Old French] I’ve [OE] read [OE] on [OE] Substack [Silicon Valley English].