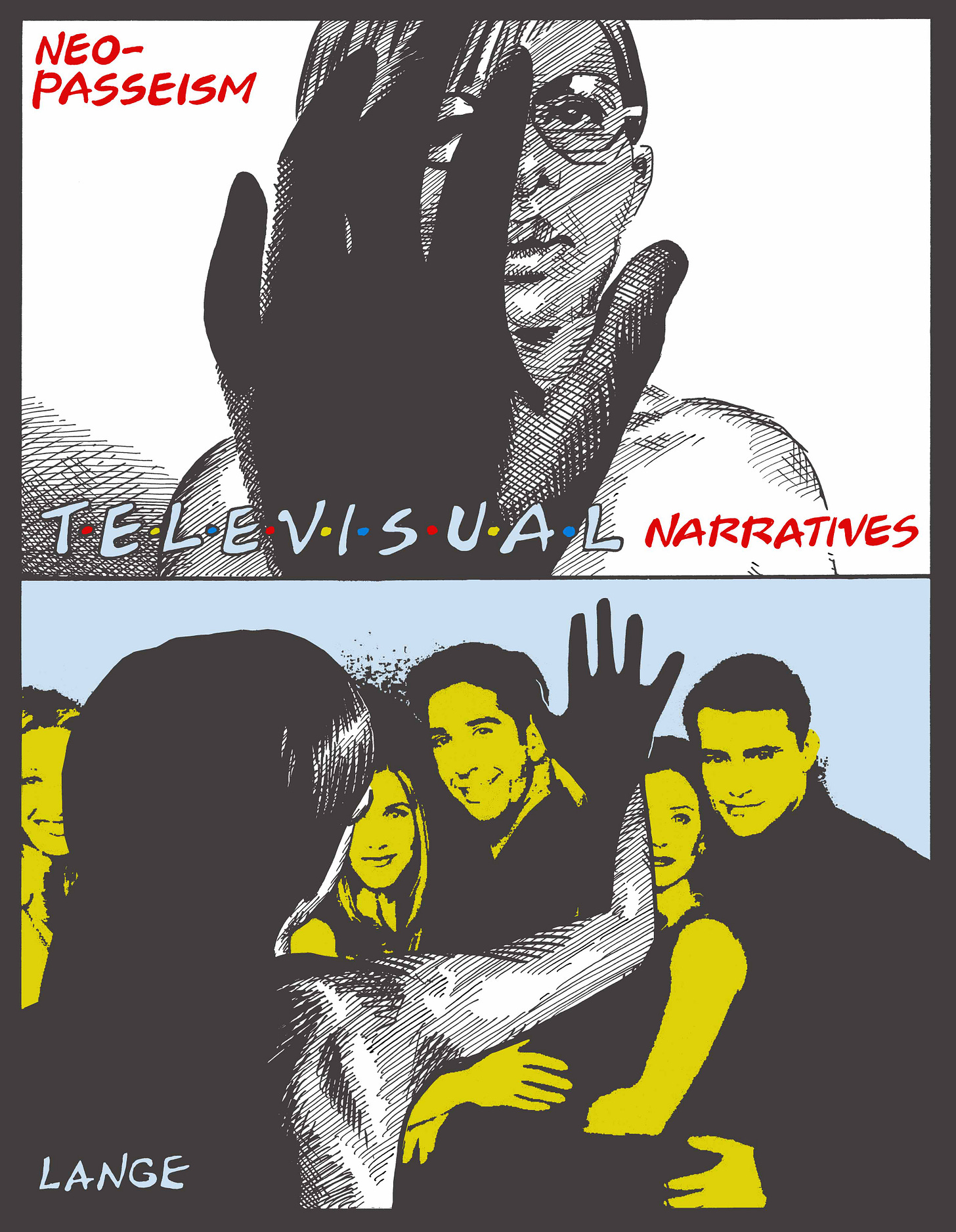

Televisual Narratives

So-called "Video Editing" Counterfeits Theatrical Performances for "Prestige Cinematic Motion Picture Films and Television Shows"

“The 20th century famously foregrounded its commercial deployment of technology derived from Edison’s kinetoscope and Muybridge’s preceding zoopraxiscope, marshaling cameras and film projectors to produce ‘cinema’ and, later, ‘television.’ The earlier devices, originally gimcrack amusements on the level of a magic lantern show or mere kaleidoscope, suddenly became freighted with supposed artistic import. ‘Film directors’ were announced, improbably, as auteurs, or authors. The postwar generations stared intently at television screens to passively observe attempts at narratives produced through the chopping and changing of ‘video editing.’ It seems difficult to believe that this was ever taken seriously on a mass scale when the live provocations and true enveloping spectacles of the theater and opera were available, yet it certainly occurred. Even now, the last living remnants of this midcentury cohort still ‘tune in’ to stare at their televisions, hoping to make sense of the world through news programs and entertainment shows.

These ‘visual media’ and their descendants in various Reels, TikToks, douyins and the like strike us as rather quaint. How can a series of two dimensional ‘moving pictures’ giving the illusion of a theatrical performance through ‘editing’ compete with real theater, much less the total artwork known as opera? Newer artforms altogether put televisual narratives to shame; viewed from the first half of the 21st century, it seems clear that electronic gaming is the true Gesamtkunstwerk. We could give examples of games whose comprehensive narrative and graphical artistry already eclipse any cinematic auteur, but our readers of distinction should be familiar with them already.

We react with disbelief and disdain to the so-called ‘Golden Age of Prestige Television’ and the like. Incredulity towards televisual narratives forms a basic component of aesthetic hygiene: not for anything in their content, but for their structure. Televisual narratives, no matter how seriously intended, retain much of their magic lantern carnival-kitsch origins, and mimicking theatrical performances with so-called ‘video editing’ is the true death of patience by a thousand cuts.”

— Justin Isis

“Historically, the main impetus of television has never been to present well-crafted art or entertainment, but to generate—by whichever means necessary—a high viewership that justified charging premium fees to advertisers. In the past decades this model has expanded to encompass subscription streaming services, yet the imperative remains not in aesthetic expression but in the maximizing of engagement metrics and the fomenting of compulsive consumption via creative homogenization.

The average television series, streaming or otherwise, is a soporific designed to occupy your time while demanding nothing of your intellect and providing nothing to your soul. The modern televisual narrative congratulates itself for its competence, its lack of risks, its predictability, and its constant reassurance of customers’ values—qualities we appreciate in a mortician, but not in a medium that strives for illimitable dominion over our collective attention and imagination.

Neo-Passéists are allergic to silence, hostile to nuance, and incapable of separating genuine desires from the phantom appetites generated by algorithms. Their dream of art that revolves around ‘relatability’ and ‘authenticity’ is fulfilled through media bubbles that create personalized, self-reinforcing pseudo-realities where genres have almost entirely replaced the possibility of authentic stylistic movements, and every story can now be neatly sorted into a predefined pen where even attempts at subversion are swiftly squashed into their own predictable coterie—the ‘dark’ or ‘elevated’ take on a familiar story or trope becomes its own boring orthodoxy. Algorithms inherently marginalize non-conformity: niche, challenging, or slow-paced content struggles against a tide of group-tested sameness. Diversity often feels like a checkbox exercise within homogenized genres, silencing quieter, outer, complex voices in favor of the already palatable.

Content is no longer primarily judged on artistic merit or cultural value, but on its ability to trigger dopamine hits to keep viewers ‘engaged.’ The binge-watch is the final victory of the consumer model over the artistic experience, an act of gluttony that starves the intellect and provides no nourishment. The original wait between installments was never a defect in the delivery system, but a necessary crucible. The complexities of a story can only be untangled and savored during the silences between transmissions.

To avoid capitulation, take part in an active and blasphemous resistance: reject engagement metrics and ratings as measures of value, actively seek art that defies categorization, support creators operating outside the franchise feudalism, embrace work that demands effort and fractures (but does not merely ‘subvert’) expectations, and pursue anything that awakens senses beyond sight and sound. Employ duplicity to conceal content beneath layers of subtext that cannot be parsed by algorithmic colonization, make art that remains a moving target impossible to pin down and fully commodify. Otherwise, remain a docile host browsing the well-lit tableau of a marketplace with infinite choice but zero substance, forever wondering at the nagging but hollow pang that there is nothing left to watch.”

— Ramon Alanis

“Throughout history a large percentage of mankind has had a vested interest in the viewing of other human beings performing diverse modes of narrative fiction. From the theatrical culture that flourished in the age of Classical Greece, to the Noh dance-dramas of Japan, to the mystery plays and miracle plays of medieval Europe, to the public playhouses that sprung up in London during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, to the epic Wagnerian operas of the 19th century, to the Indonesian wayang puppet theatre, and the many other examples one could cite, the bottom line is that we not only like to watch other people doing things, but sometimes also be performers in our own right (the bastardized and decadent strain of this trend is perhaps the proliferation of YouTube and TikTok videos). One thing most of the above had in common was that the spectator was often required to physically go and see the performance in question. There were of course exceptions to this rule; for example: the wandering minstrels/troubadours/jongleurs/minnesängers that literally had to ‘sing for their supper’ in taverns, and in Elizabethean England acting companies would frequently perform in the homes of the nobility or at the palatial courts of kings and queens. But the general rule was, if one wanted to take part in the communion between performer and audience member, one had to physically attend the spectacle. The spiritual component alluded to here is deliberate: see the links between Classical drama and the Greco-Roman mystery cults, or of course the mystery plays, which bought various biblical scenes to vivid life for their mostly illiterate audiences.

Obviously, the development of televisual art forms in the 20th century had a redefining aspect in the communication and transmission of performative narrative storytelling. One positive development was that, for people who did not have access or could not afford it, now narratives as performed by human beings could be delivered directly to them, be it via the movie theater or in the comfort of their own homes (in the case of television, that is). The tradeoff was a shedding of intimacy and the severance of that almost sacred bond and spectral link formed between performer and audience (on a related note, anyone who has ever been to a music concert can tell you there’s a big difference between being there in person and watching it on a screen at home). And initially, the transition was far from a smooth one. Early British silent films, in particular, were very stilted and stage-bound affairs (which is ironic, when you consider that the world’s first moving picture was shot in Leeds), which was hardly surprising when one factors in the knowledge that many of them were adaptations of plays. It would take the outside influences of both Hollywood and continental Europe to change this state of affairs, as refracted through the corpulent prism of its native son, Alfred Hitchcock. The young Hitchcock was sent to Germany in 1924 to work as an assistant director at the UFA, where he studied under F.W. Murnau and was thus exposed to the innovative techniques of German Expressionism, lessons which he would go on to apply to his own films throughout the course of his long life and career (Hitchcock, perhaps almost more than any other mainstream director of his time, was intensely aware of the importance of the visual element to this new narrative medium, famously saying, ‘In many of the films now being made, there is very little cinema: they are mostly what I call ‘photographs of people talking.’ When we tell a story in cinema we should resort to dialogue only when it's impossible to do otherwise’).

I would be the first to admit that I’ve seen just as many movies and watched just as much television as the next person (within moderation: in the course of a day, generally less than a half-hour of my time is devoted to TV watching, for the most part). But there’s no denying that the televisual narrative is by far the most passive of the art forms, in that it requires but little imagination on the part of the participant. You don’t get that imaginative interplay that is generated between the writer of books and the reader of books, in which, through a collaborative process, a Gysinian third mind is engendered. The writer provides information as to how the characters look, what their voices sound like, the environments they move in, and so on, but the interesting thing is that each reader who reads a book takes that information and rebuilds it in their own mind; it’s very much like the writer is an architect providing a blueprint, with the reader tasked with building it in their minds as they read; thus, they to some extent are also encouraged to take part in the creative process. And as a result of this, if you could take a mental picture of how the author imagines a character to look or sound, then compare it to a number of mental pictures generated by the readers, you would likely get a number of mental pictures that were somewhat similar in some areas but also wildly divergent in others. The same can be said for radio programming, for while the listener is provided with the voices of the characters, they still need to ‘build’ the appearance of the characters and their environs in their mind’s eye. Even video and computer games often offer some freedom of choice and agency on the part of the gamer. And listening to music can generate synesthetic thought-forms/‘coherent erections’ in both the material and the astral world, according to the theories put forth by the theosophists Besant and Leadbeater (‘sound produces form as well as colour, and that every piece of music leaves behind it an impression of this nature, which persists for some considerable time, and is clearly visible and intelligible to those who have eyes to see’).

By comparison, with televisual narratives, you don’t really get that kind of creative collaboration between artist and consumer, as the viewer is generally at the mercy of the production. Setting aside those with visual or hearing disabilities, with a TV show or a movie, everyone pretty much sees and hears the exact same thing as everyone else. Granted, it could be argued that a professional cinematographer, set designer, or costume designer might look at such scenes and pick up on little details that the layman may not notice, but these are largely minor technical considerations. In short, the imagination of the audience member is not really tested in the same way as they are with some of the other art forms described above. It is ultimately a submissive experience, and thus properly suitable for a society that seems to be mainly composed of the ‘power bottom’ sexual persuasion. Not content to let us create our own inner version of the narrative and its constituent elements, the Black Brothers of the televisual narrative centers of pestilence are like conquistadors of the Imagination, theocratic Inquisitors obsessed with stamping their own vision of their so-called ‘art’ on our hapless modes of consciousness. Like some doomed Victorian barrow-excavator pinioned in the all-encompassing gimlet gaze of Lord Panswyck, our minds have slowly become barren battlefields and psychic wastelands polluted by the celluloid fell beasts emanated by our archonic networks and mass media content providers. Is it any wonder, then, that the creative powers of the great masses of humanity have almost terminally stagnated? As William S. Burroughs wrote in The Cat Inside, ‘The magical medium is being bulldozed away...the whole magic universe is dying.’

I feel that one of the great emotional plagues afflicting Western civilization in our times is that our entertainment and artistic humors are out of alignment and unbalanced. I don’t feel as if televisual narratives are necessarily evil by nature (though if Plotinus had foreseen a Great Chain of Being dedicated to the narrative arts, televisual narratives would certainly be on a lower strata of evolution, most likely somewhere near the mineral level), it’s just that their cultural supremacy (and here I’m speaking particularly about television) over all other forms of the arts has gotten out of hand. More moderation is needed…I feel that one should strive to read books, listen to music, play video & computer games, and watch TV and movies in a fairly balanced manner, so that holistic harmony in the individual may be achieved.”

— James Champagne

“Television is the most totalitarian form of entertainment to emerge in the 20th century, which is almost certainly why, at least in the Anglosphere, there was never a unified avant-garde movement in television beyond isolated incidents rare as eclipses. The closest analog—public access television—remained strictly local until archived footage began being uploaded en masse on YouTube which, in turn, has helped make traditional television functionally obsolete. All boob, all tube.”

— Colby Smith // YUUGENPRAXIS

“Rejoice! We have conquered the era of bad TV and now live in a Golden Age of Prestige Television, perhaps dying now, but who cares! If it does die, we can watch all the shows we missed! There’s been such an abundance of televisual riches, the media critics tell us, that no one can watch them all. The past fifteen years of magnificence have provided such a bounty that we would never run out of well-rated but under-viewed character studies.

A small sampling of the most prominent of these can’t-miss wonders might include Mad Men, Breaking Bad, Girls, Orange is the New Black, and Game of Thrones, alongside more recently concluded shows, such as Succession. What do these shows have in common? Amoral characters that range from obnoxious but mostly harmless—the youths of Girls—to truly awful—the media billionaires of Succession. Each show confronts us with the same supposedly novel approach: the abandonment of evaluation in favor of explanation. The characters in these shows perform awful acts that we recognize as awful: destroying each others’ lives, committing murder or rape, enabling global capitalism to destroy the planet at an ever accelerating rate, or seriously and directly harming children. But, as constant viewers, we’ve been trained to wait, to hold in any initial disgust we might feel and wait for the explanation: ‘I didn’t like how he murdered those kids, but I bet he had a good reason. Let’s wait and see.’

Inevitably, these acts are recontextualized, allowing us to feel relief as every character is humanized: Hannah Horvath has mental health issues; the Roy siblings have a mean dad; Walter White doesn’t have good health insurance; and Jaime Lannister is sad sometimes. This recontextualization sometimes begins immediately, with clues that are interwoven with the act: ‘He cried while he murdered those kids, so there must be something going on here.’ Other times we’re met with the tension of a build-up over several seasons, revealing latent humanity, in a slow and dramatic multi-episode reveal: ‘So that’s why he murdered those kids—kids were mean to him when he was a kid.’ Anything anyone does, no matter how horrible, is just human nature. And, hey, we’re human, too, so we shouldn’t judge, right?

What of the alternative: evaluation? Prior to the success of so-called prestige television, much of dramatic televisual narrative offered easy moral judgment, as endless procedural dramas presented multiple weekly doses of cartoonish villains, in shows like Law and Order and its numerous progeny. In each episode, we are given a criminal or villain to evaluate and, in turn, hate: ‘I’m so glad those wonderfully gritty policemen caught the guy who murdered those kids and sent him away forever!’ These shows, of course, still exist, for the less sophisticated viewer. Otherwise how could viewing prestige television make the cultured viewer feel superior? Unfortunately the evaluation paradigm doesn’t make for better or more varied television than the explanation paradigm. In each case, whether we’re treated to the humanity of the archetypal bad person or allowed to hate them, we encounter the same patterns over and over again.

Can televisual narratives be saved? There are clues if we look farther back, to eras when television executives, presumably not paying attention, more commonly allowed nuance to slip into even mediocre episodes of long-running shows. As an example, consider a relatively poor season one episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation titled ‘When the Bough Breaks.’ In this episode, the children of the Enterprise are kidnapped by a dying society of idiots, the Aldeans, who don’t know how any of the machinery that keeps them alive works; unless they get some kids to instruct in their idiot ways, they’ll be the last. The clumsy and obvious reveal is that it’s the magic machines that keep them alive that are also causing their society to die out, as they can no longer procreate due to magic machine radiation. Despite its silliness, this episode does have some nuance: the Aldeans are condemned for kidnapping children and attempting to offer compensation for them, but these acts are also explained: who among us might not be an idiot if we’d always been supported by magic machines? And, while still holding the Aldeans in contempt, the ever-forgiving crew of the Enterprise helps the Aldeans turn off their magic machines, saving their dying race—or more probably condemning them to death, since they don’t know where food comes from. Both explanation and evaluation are offered to the viewer, who is shown how the Aldeans are worthy of both pity and disgust.

At first, this simple looking-back seems to lead to a simple formula for better televisual narrative: include characters who perform awful acts, explain the motivations behind those acts, but let us judge the acts and their perpetrators. The lesson is more complex. The failure of both prestige television and of procedural television is in the overall restriction of form, not in the abandonment of specific forms. Shows like Star Trek and Twin Peaks succeeded in creating interesting episodes and character arcs to the extent that the writers’ rooms and directors were unsupervised—allowed to experiment with different forms of storytelling. The consequences of this experimentation was a profusion of form, sometimes poorly written schlock, but other times beautiful and wonderful.

Lack of restriction does still very occasionally sneak into televisual narratives, often when the audience of a popular show eludes the current set of metrics that executives use to dish out just the right narrative. Consider Bojack Horseman: the entire six-season arc is dedicated to explaining the effects of intergenerational trauma, self-hatred, misanthropy, and abuse. Explanation in this case does not lead to a dearth of evaluation. Bojack and other characters are consistently portrayed as traumatized people doing awful things—things that we are not required or even invited to forgive. Bojack Horseman also regularly experimented with form, featuring, among others, episodes that experimented with the confusion of dementia, a silent world without communication, and the experience of a lengthy binge of drugs and alcohol, resulting in death and loss. Bojack Horseman succeeds because it occupies many forms, allowing the viewer to be challenged as they encounter a variety of narrative modes.

The lesson here is that restriction doesn’t always breed creativity. Avoiding restriction of form and instead experimenting wildly is what allows televisual narrative, and any art, to elide passéism.”

— Siobhán M. La Grippe

[…] you can be transported to another place. Films can take you anywhere.

— Michael Jackson

[It’s] not blood, [it’s] red.

— Jean-Luc Godard

Captain EO launched at Disneyland in September 1986. Directed by Francis Ford Coppola and produced by George Lucas, the Disney/Lucasfilm co-production featured a peak-fame Michael Jackson, alongside a troop of various muppet creatures, in a 17-minute spectacle that blended Return of the Jedi vibes with an MTV sugar spike. It was loud, it was stupid, and it was the first blockbuster production to go beyond 3D gimmicks and incorporate what would come to be known as 4D film. Depending on where and when EO was screened, audiences were variously treated to chair hydraulics, lasers, water spray, smoke effects, and an innovation known as ‘leg ticklers.’ Despite its compliance with traditional Euclidian space, this was touted as ‘FOUR DIMENSIONS.’ As images leapt off the screen, they were accompanied by an array of additional sensory effects—an idea that Walt Disney himself would have surely approved (had he been able to look past the King of Pop’s incessant ‘woo-hoos’ and asexual crotch-crabbing).

Despite a bad script and Jackson’s increasingly bizarre public profile, Captain EO was an unqualified success, and paved the way for future theme-park-exclusive productions like Jim Henson’s Muppet*Vision 3D (1991), Honey I Shrunk the Audience (1994), and James Cameron’s awkwardly titled T2-3D: Battle Across Time (1996). As the public became more familiar with the presentation format, the ‘3D’ title appellations were updated: Pirates 4D (1997), SpongeBob Squarepants 4-D (2002), Shrek 4-D (2003), and on and on. With the exception of Captain EO and SeaWorld Ohio’s Pirates 4D, these park-anchored short films were almost always attached to pre-existing franchises and intellectual property (though in the case of the former, Wacko Jacko could reasonably be considered an IP product himself). I’ve seen some of these films and don’t mind admitting that I’ve been startled by a spray of mist, flinched at a sudden 3D projection, and just generally oohed and aahed throughout the runtimes. These cross-stimulating televisual narratives are undeniably clever and amusing—albeit ultimately forgettable. Once the patterns become clear and the novelty wears thin, it’s tempting to consider how the 4D techniques could be applied to truly original works, something beyond Star Wars and LEGO and Marvel...something more like Béla Tarr’s 439-minute Sátántangó.

It’s even tempting to imagine the theaters removed from the theme parks entirely, and relocated to remote and grandiose land art locales (like one of the two trenches that form Michael Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) in the Moapa Valley). Or what if auteur-driven 4D theaters were incorporated into the nightclubs of Dubai? It’s tempting—no, necessary—to imagine how these environments and various effects could be elevated generally into something just MORE.

Surely, within the framework of ‘four dimensional’ televisual narratives, there is a potential for something approaching what we might call, for lack of a better term, a Ritualized ASMR Gesamtkunstwerk—a total work of art which stimulates and teases the full array of senses, with the aim of inducing an altered state of consciousness conducive to advancing magickal operations. To get a sense of what this would entail, one need only imagine if Kenneth Anger had had the resources of a Disney or Lucas: lasers carve planetary symbols, the fog machine is infused with incense, chairs shake as Babalon’s name is vibrated. And the spray effect? Baby, that’s not cum, it’s white magick.

‘Eos’ is Greek for ‘dawn.’ Francis Ford Coppola took inspiration from this term—and the sexually voracious goddess of the same name—while researching themes and thinking of titles for his early 4D film, and the word was eventually used in an altered and abbreviated form: the ‘eo’ in Captain EO. It is now time for the Neo-Decadents (with the help of a few wealthy and aristocratic patrons) to finish the work that Coppola started, to take four dimensions to the next evolutionary step. It is time for eos. It is time for a hidden Brutalist theater that is a shrine to a dark goddess. It is time that men know the true meaning of mist spray and ‘leg ticklers.’ It is time for a new dawn.”

— Aaron Lange

art by Aaron Lange

This reads like a ritual disguised as critique—furious, baroque, and oddly devotional. Each voice hums with its own fractured psalm. Aesthetic hygiene as liturgy. Gorgeous.

The bass guitar pulses between the 5 and the tonic, without a 3 to imply major or minor. For the moment there is only ambiguity. The melody begins as the first real chord change happens. Definitely major, happy and bouncy.

"It's a rare condition, this day and age,

To read any good news on the newspaper page.

And love and tradition of the grand design,

Some people say it's even harder to find.

Well then there must be some magic clue inside these gentle walls

Cause all I see is a tower of dreams

Real love burstin' out of every seam."

*Randy Newman or whoever leans in close to the mic and moves his shoulders high in a sustained shrug*

"As days go by,

We're gonna fill our house with happiness.

The moon may cry

*leans even closer and drops shoulders*

"It's the bigger love of the family."

*Newman or whatever throws his head back, face up but eyes closed, as he lays down the sickest piano riff ever*

I feel like Urkel was giving me the hard-press into ritual occultism, a full 35 years ago. Its the bigger love of the family. Family, work thy will.

😈 ⚫️ ☯️

👿 ⚪️ ☯️