“Within the past few years, Manosphere advocate Roosh V, formerly known for his aggressive support of (heterosexual) promiscuity, has publicly abandoned ‘fornication’ in order to pursue a lifestyle of renunciation as an Eastern Orthodox Christian; while alt-right pundit Milo Yiannopoulos, formerly known for his aggressive support of (homosexual) promiscuity, has declared himself ‘ex-gay’ and promised to pursue a lifestyle of renunciation as a Catholic devotee of St. Joseph. We could mention also disgraced comedian and actor Russell Brand, and even the activist Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who have both subjected themselves to similar conversions. While some may be surprised by these turns, they will be familiar to those with an understanding of historical Decadence.

‘My dear boy, you are really beginning to moralize. You will soon be going about like the converted, and the revivalist, warning people against all the sins of which you have grown tired.’ —Oscar Wilde, The Picture of Dorian Gray

In the 19th century, notable Decadent figures like Aubrey Beardsley, Lord Alfred Douglas (‘Bosie’) and Wilde himself were known for abandoning their previous lifestyles and converting to Catholicism, often when death approached. Although the circumstances of the time and certain ulterior motivations can be taken into account (‘Bosie’ was concerned with losing his inheritance), there is little reason to doubt their sincerity. And in France, Huysmans is known for similarly abandoning his lifestyle and literary preoccupations to embrace the Church.

‘After Les Fleurs du mal I told Baudelaire it only remains for you to choose between the muzzle of the pistol and the foot of the Cross. But will the author of À rebours make the same choice?’—Barbey d’Aurevilly, reviewing Huysmans

The Huysmans Flip can be defined as a steadily growing disgust with Modernity culminating in a Christian conversion. Oftentimes the Flip correlates with aging: one is simply too tired to keep partying, and has grown bored with the scene. The pervasive sense of exhaustion impels one to look for answers further afield, in austere spiritual avenues. Now the conversion logic of the 19th century is being recapitulated by Huysmans Flippers in the 21st century, many of them alt-right types whose underlying reactionary nature was only barely concealed by their superficial embrace of hedonism. When the hedonic treadmill has ground you down, it is not so difficult to see Tradition as an answer to your restless longing.

ASCETICISM + NOT BEING ABLE TO ENJOY YOURSELF = THE FOOT OF THE CROSS

Is the choice offered by Barbey d’Aurevilly really a stark binary? We suggest there are in fact three options:

1. Muzzle of pistol

2. Foot of cross

3. Decay Accelerationism (regeneration through imagination + further excess)

In other words, we encourage you to take a brief break and then resume excess sinning with renewed imaginative energy.

It may be wondered whether more sophisticated types are really in danger of a Huysmans Flip. After all, neither Roosh nor Milo are particularly perceptive in any sense that could be put forward. However, are we in danger of a different kind of Flip, that of succumbing to concealed Christian logic? We note that much current secular morality, descended from Christianity, still opposes your decadence, albeit under different terms:

"Stop fucking so many girls, don't be a predator."

"Stop fucking so many boys, don't be a slut."

"Stop doing so many drugs, it's bad for you."

"Stop releasing so much art, you're supposed to be miserable and silent."

“Stop enjoying things, the world is so terrible.”

The function of this secular morality is to render you a suffering, alert, conflicted, ‘compassionate’ monitor of yourself (aka a neo-Victorian Christian). We advise you to avoid this and keep sinning; it is much more enjoyable.

’You complain about fucking being ‘monotonous.’ There’s a simple remedy: cut it out for a bit. ‘The news in the papers is always the same’? That’s the complaint of a realist—and besides, what do you know about it? You should look at things more carefully … ‘The vices are trivial’?—but everything is trivial. ‘There aren’t enough different ways to compose a sentence’?—seek and ye shall find … You must—do you hear me, my young friend?—you must work harder than you do. I suspect you of being a bit of a loafer. Too many whores! Too much rowing! Too much exercise! A civilised person needs much less locomotion than the doctors claim. You were born to be a poet: be one. Everything else is pointless—starting with your pleasures and your health: get that much into your thick skull. Besides, your health will be all the better if you follow your calling … What you lack are ‘principles.’ There’s no getting over it—that’s what you have to have; it’s just a matter of finding out which ones. For an artist there is only one: everything must be sacrificed to Art … To sum up, my dear Guy, you must beware of melancholy: it’s a vice.’ —Gustave Flaubert, letter to Guy de Maupassant

— Justin Isis

“‘I don’t want anything to do with that pigsty of Naturalism anymore!’ Joris-Karl Huysmans wrote in a letter to his friend Gustav Guiches. ‘Now what? What is left? Maybe occultism. Not spiritualism! The clownery of the mediums, the wickedness of old ladies that turn tables! No: occultism! Not the ‘up above,’ but the ‘underneath’ or the ‘aside from,’ or the ‘beyond’ of reality! Lacking the faith of the Primitive and the first communicant that I would like to have, there still is a mystery that ‘demands’ me, and that occupies my thoughts.’

Huysmans, like so many figures in art, was dissatisfied with the idea that every aspect of human behavior, all obsessions, could be explained. Naturalism practiced to the exclusion of all else engenders an Aesthetic melancholy in the hearts of the already Aesthetically sensitive. Huysmans, even deep into his later life Catholic apologetics, remained in that melancholy. While the snippet of his letter to Guiches rejects spiritualism, it speaks to Huysmans’ longing for a world shrouded in mystery; one best exemplified by the simpler, more pious trappings of the Middle Ages and the primordial evils religion sought to suppress.

While the world was never quite as ethereal and misty as wistful authors wished, the ancient mysticism of Catholicism in particular was more fantastical, more mysterious than the banality of industrialized Europe. Modernity brought with it a sharp focus on the miserable lives of inconsequential people and enshrined their misdeeds, afflictions, and perversions as immediately natural. Sin itself was no longer a plague rendered by demonic forces but the tempest of humanity’s inherent foibles. There’s nothing sexy about every vice and compulsion being explained when your heart longs for a diabolic explanation and a performative spiritual remedy.

Not every person who undergoes a Huysmans Flip will be as considered as Huysmans himself. Some seek to flee a life of excess and sin on their deathbeds as the skepticism that fueled their lives depletes. Others find warmth in donning conservatism and the cudgel they can more freely swing against people that displease them. No matter how the flip begins, be it out of fear or a desire to align oneself with more ancient oppressions, every motivation begins with tendrils of benzoin caressing that Aesthetic melancholy.

Of note is the wave of flips we’re seeing as a result of Christian Nationalism and Evangelical obsessions with the demonic. Huysmans was also taken in by the cultural fears of Satanism in the late 19th century. The conspiracy theories we see from conservative voices today, so obsessed with secretive cabals of powerful diabolists and international orders of profane elites, are consonant with much older fears. Even in Huysmans’ lifetime the murmurings of black masses, Satanic rites within Freemasonry, and the corrupt dedication of priests, were rooted in Church control but took on new life through the same industrialization that so demystified reality.

While writing Là-Bas, Huysmans fell into the conspiratorial hole of demonic priests. His source for this is likely to have been Remy de Gourmont’s then lover Berthe de Courrière. Courrière was a model and passionate counterculturalist. Reuben van Lujik’s account of her in Children of Lucifer describes her as a devoted occultist infatuated with priests and the aesthetic mysticism of Catholicism. Her home was full of ecclesiastical trinkets, including a pulpit where she kept a volume of Sade’s work bound like a bible. Her infatuation with priests ultimately led to her discussing Chaplain Lodewjik Van Haecke with Huysmans, who would later serve as the direct inspiration for the villainous Canon Docre in Là-Bas.

At some point after meeting Van Haecke, Courrière was institutionalized following a mental health crisis. Courrière’s account painted Van Haecke as a powerful and seductive Satanist that had lured her into his dark works. Her resulting breakdown occurred after she fled the scene. While this may read as unrealistic to modern eyes, for Huysmans (already searching for threads of Satanism) it provided veracity to the idea that there might be more behind the ramblings, in much the same way that Q drops provided enough plausibility for the susceptible to believe that there were Satanists eating children in the non-existent basement of Comet Pizza.

While I don’t think Huysmans was as far gone as QAnon conspiracy theorists are today, both the author of Là-Bas and modern conspiracists share a disillusionment with naturalist explanations. The aesthetics of a gray world leave the mind seeking answers that are far richer, more seductive, and ultimately more destructive than humdrum facticity. When you reject reality in favor of divine righteousness and demonic seduction, you take the burden of proof off yourself and can begin to convince yourself of a great many things, all in pursuit of waging war with the forces of evil.

Which is where we get back to whatever the hell Evangelicals are doing today. An hour spent on TikTok will show you an array of conservative aesthetics, from clean girls maligning self expression to disgraced celebrities explaining away their moral failings as the devil’s work. All modernity has done for these figures is disconnect them from the spirituality that they now think protects them from criticism. Piousness, in all its performative glory, is the armor of god shielding them from the horrors of their own actions. Self-expression, critical thinking, and hues beyond beige are the Devil’s playground.

It’s no surprise to me that as Evangelical thought rushes to label anything and everything that isn’t white, heterosexual, and cisgendered as Satanic that Evangelicals themselves are eying aesthetic Catholicism. While the Church is far from a liberal entity, the practice of cultural Catholicism is not the fire and brimstone experience that films would lead the modern Christian to believe.

Modernity gave humanity the tools to assess and explain wickedness, but in doing so removed the mysteries of life. Or, if your worldview is steeped in the idea that the unknowable is unknowable by design, that conflicts with the idea that with enough collective effort we can unveil the very fabric of existence. That’s unglamorous! Where are the centuries of mortal sins? Why would millions of people subject themselves to the guilt and pageantry of organized religion if we could just answer the questions? Why shouldn’t humanity forego study in favor of instinct and Biblical instruction? Life was much simpler, purer, and holy when we feared god and toiled for the promise of eternal peace.

The idea that this suffering is divinely intended and not manufactured by humans to use against humans, is a facet of the aesthetic melancholy I mentioned earlier. When we see the world too clearly, the filth seems pointless. We are, ourselves, filth in a grand tapestry of wickedness, and without faith and the ancient spectacle of religion, will not transcend this animal existence.

To me, the Huysmans Flip is indicative of someone who realizes that religiosity is a tool. How someone might use that tool depends on the necessity for it. Some will view it as a wholly spiritual transformation and occupy themselves with the beauty they find there. Others will use the tool to protect themselves from their bad behavior and, more often than not, seek to influence others to take up arms to fight their accusers. The flip is cowardness to some degree, and a disillusionment with the reality that humans are very dull and their behavior predictable. The truly devious realize this and, understanding the power religion has over others, use their talents to claim that power once their dalliances leave them exposed and alienated.

While I have no intention of seeking redemption on my deathbed, I am not yet close to it, and perhaps a few more decades of luxuriating in the complexities and mysteries of life will see me kneeling at the end. For me, the void caused by Aesthetic melancholy is filled by curiosity and a hearty appreciation for how humans perpetually bamboozle themselves seeking answers. To resist a Huysmans Flip, it is important to never lose one’s ability to see beauty in the highest and lowest of places. Existence itself is sacred and life is better spent unravelling personal mysteries than seeking to close a curtain on curiosity when reality is too uncomfortable or too banal to tolerate.

The grandest cathedrals were made by human hands, designed by humans seeking to harness the diaphanous presence of divine mystery. The allure of conservative obedience is tied to this desire we have to be in awe, and the notion that to achieve it we have to jettison all the understanding and science we’ve conjured up and return to a primitive state. But a Waffle House at 4am is as sacred a place as St. Peter’s Basilica, and the unfettered and often chaotic humanness of that space a divine mystery.”

— Hadrian Flyte

“I will confess that I’ve never much cared for the derogatory term ‘Huysmans Flip.’ First off, I’m not sure how comfortable I am with the idea of J.-K. Huysmans being stigmatized as the poster boy for converted writers, especially when one can easily name a number of far more famous examples who converted to Christianity (be it Catholicism or some other strain), whether ‘Moderns’ (Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Verlaine, Wilde, Waugh, T.S. Eliot) or elseways (G.K. Chesterton, C.S. Lewis, et alia). Secondly, I feel that when most people see the word ‘flip’ (especially in regards to a decision made by someone), they fall under the impression that the action of ‘flipping’ is a glib or frivolous affectation/action, which, in the matter of Huysmans, couldn’t be further from the truth. Semantically speaking, in Huysmans’ case it’s not even accurate, as he wasn’t truly a convert in the classical sense of the word (for going by the theological definition, in Christian terms a convert is a non-Christian who converts to Christianity) but rather a revert (in that Huysmans began life as a Catholic, fell away from the faith after childhood, then returned to it later on in life). If anything, for Huysmans it was less a flip and more of a somersault, though perhaps this is splitting hairs.

To return to an earlier point, and again going by the definition of the word ‘flip’ as a ‘quick, sudden movement,’ we can see that Huysmans’ ‘second conversion’ was anything but quick or sudden; a Naturalist to the end, he famously compared his second conversion as being analogous to the digestion of the stomach, a gradual process whose inner machinations were all but invisible to him. Huysmans formally reentered the bosom of the Church in 1892 (during his religious retreat at a Trappist monastery), but the seeds of this reversion can be traced all the way back to his landmark novel Against Nature, even if he was unaware of it on a conscious level at the time; in the preface he wrote for the 20th anniversary edition in 1903 (which was included as an appendix to the Dedalus Books reprint in 2008), Huysmans retrospectively identified his most famous book as a ‘…primer for my Catholic work.” Huysmans began tentatively haunting churches and chapels in late 1890 (around the time he was finishing up his novel on Satanism, Là-Bas), but it wasn’t until 1891 that he seriously began considering writing a ‘white novel’ and also entertaining the notion of going back to Christianity: that was the year he also began forming a friendship with a priest (Abbé Arthur Mungier, who for a time acted as his spiritual director) and began heavily reading and researching some of the great works of theological literature and the lives of the saints. As mentioned above, this all culminated with his religious retreat in 1892, where, at the Trappist monastery in which he was staying, he formally confessed and also took Communion again for the first time in ages. However, it must be pointed out that during this time Huysmans was also in close company with the Abbé Boullan, a Satanist who had tricked him into thinking he was a holy man and mystic (the relationship between Huysmans and Boullan is a long, complicated, and fascinating one: interested readers are advised to consult the essay I devoted to the book Là-Bas, which first appeared on Dennis Cooper’s blog some years ago, and which I humbly feel is perhaps the most exhaustive article on the novel that one may find in the English language online). Therefore, during the same period in which Huysmans was struggling to regain his lost faith, he was also consorting with dabblers in black magic and diabolism, and getting involved in psychic wars with Rosicrucians. This struggle manifested in the difficulties he experienced with writing En Route, his ‘white novel’ and follow-up to Là-Bas, which initially seemed to have been a far more lurid novel about the war between flesh and faith (the working title in English would have been translated to something like The Carnal Battle), before he changed his mind on its direction.

My point in rehashing all this ancient history is simply to make clear that Huysmans’ decision to revert to Catholicism was very complicated and not something he did glibly, like flipping a coin. It was a long and difficult process (for gazing into that Gilles de Rais-shaped Abyss and then subsequently rejecting the Hole in Things to focus instead on the higher spiritual pathways caused him great strain both physically and mentally, and, if one takes his ‘assassination by office mirror’ story at face value, nearly cost him his life), and it involved a lot of hard work on his part; as previously stated, he went to different churches, spent long hours mentally debating the theological ramifications of his spiritual path (consider the extraordinary 5th chapter of the second half of En Route, in which Durtal, Huysmans’ author surrogate, undergoes a mystical Dark Night of the Soul and spends many pages wrestling with his doubts and seriously considering all the arguments against his faith), spent even longer hours immersed in researching his faith, sought out the opinions of experts in the field, removed himself to monasteries for inner spiritual reflection, all the while battling his own fleshy desires and earthly temptations. I think, if one compares him to the modern-day celebrity Huysmans Flippers, one can see that he is far superior to them, in that I suspect they haven’t really ‘done the work.’ Obviously, I cannot see into the souls of these modern converts, and for all I know they are perhaps sincere. But I think in many cases their motivations are likely far less noble (Russell Brand in particular immediately comes to mind). It’s also worth noting that today when celebrities convert, they are often widely applauded. Huysmans, by contrast, was not only shunned by some of his former colleagues, but was ridiculed in the press, and even many Parisian clerical types were out for his blood (metaphorically speaking), some of whom not only took great umbrage at his Catholic novels (one priest wrote about him that ‘this man is to Chateaubriand what a toad is to a nightingale’), but even went so far to take their case to the cardinals in the Vatican in 1898, in a failed attempt to get Huysmans’ novel The Cathedral placed on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum. Part of this clerical antipathy towards Huysmans had to do with the scorn and vitriol he tended to pour on modern day Catholic thinkers and institutions (which he saw as watered-down, lukewarm, insipid, and total philistines in the realm of the arts), and also with the fact that he quite rightly refused to renounce his profane books. In the Against Nature preface quoted above, Huysmans argued, ‘…how is it possible to appreciate the work of a writer in its entirety if one doesn’t see it from the beginning, if one doesn’t follow it step by step; and how, above all, is it possible to understand the progress of Grace in a soul if you suppress the traces of its passage, if you efface the first impressions it left behind?’ Contrast this owning up to one’s past with witch-turned-Bible thumper Kat Von D (admittedly one of the more photogenic Huysmans Flippers), who has gone to great expense blackening all of her old pagan tattoos.

A further point must be made: I think in the example of many of these modern Huysmans Flippers, their view of Christianity is simplistic (or perhaps dualistic is a better word), in that they see it as a way to inject some purity or ‘light’ into their lives, as a means of counteracting their ‘dark’ past transgressions. But I think (and the same can be said for many generic Christians) that they are ignorant of the dark (or shadow) side of the faith. I’ve long felt that a religion must need have a dark side, and the greater the religion, the larger the shadow it casts. A religion that does not have a dark side (or, put another way, that has not successfully integrated its Shadow into its gestalt, to use a Jungian term) is not psychologically whole. The moral failure of Christianity (though the same can be said about most of the other large Abrahamic faith systems) is that its institutions and followers often turn a blind eye to, or simply have an inability to acknowledge, the dark side of their faith system. We can see this in the many Christians who reduce the Bible to a set of empty platitudes, and who choose to ignore the darker (or even plain surrealistic) parts of it (on this matter, I highly recommend Kristen Swenson’s A Most Peculiar Book: The Inherent Strangeness of the Bible). Huysmans, on the other hand, was but all too aware of the dangerous pathways of Christian Mysticism, and though initially he shied away from the concept of Mystical Substitution (in which one takes upon themselves the sins of the world, so as to spare the suffering of others), in the last few years of his life he came to embrace it, and the agony he went through in his final years is truly a thing to behold…one certainly can’t imagine Russell Brand or his brethren, that right bunch of Charlies, making such a blood sacrifice on their own part. Can you live on a knife-edge, darling?

I would like to here quote a passage that I came across some time ago in the introduction that the writer Reggie Oliver wrote for his ‘Best Of’ short story collection, and which reflects my own approach to spirituality: ‘The great questions (‘Whence? Why? Whither?’) are ones which still constantly engage me. There are, I think, two mistakes one can make in life: one is to think that the questions are unanswerable and therefore not worth asking; the other is to believe that one has found the answer and that it consists in a simple dogmatic formula. The great mystics of all religions and none have taken the third course of choosing the Wayless Way, of battering their heads constantly against a Cloud of Unknowing.’”

— James Champagne

“I’ve got Nero’s name tattooed across my right hand, principally because he didn’t feed his lions often enough. But his embarrassed lions would refuse to eat the Huysmans Flipper, a slab of maggot-teeming gristle claiming up-and-down to be gold-sheathed tomahawk.”

— Colby Smith

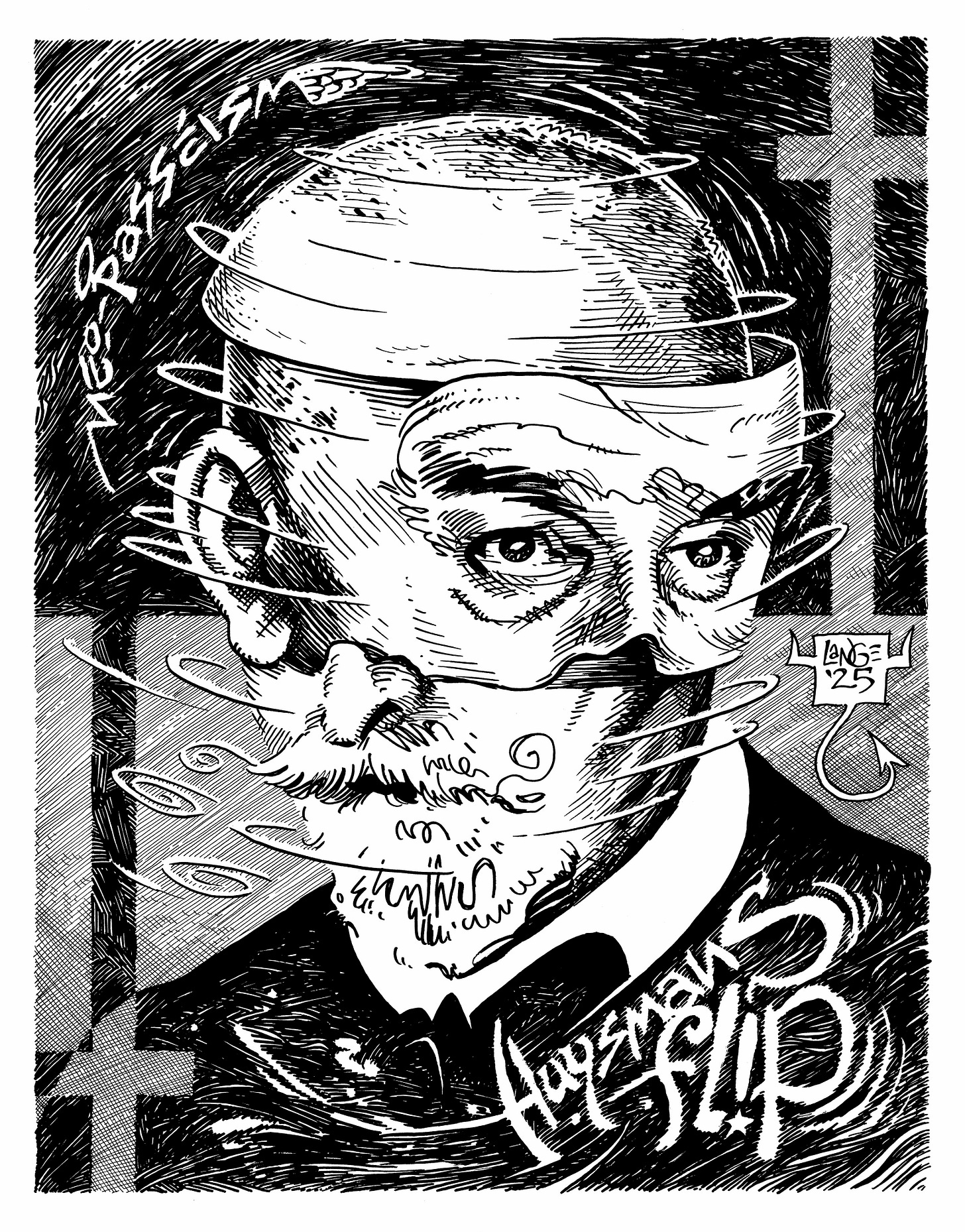

“The greatest irony of Huysmans’ ‘flip’ is that today he is most certainly read by more Satanists than he is Christians. Durtal doth protest too much.”

— Aaron Lange

“HUYSMANS ROLL: the practice or prank of attempting to induce a Huysmans Flip by offering the Barbey d’Aurevilly ultimatum at unexpected times.

EXAMPLE 1: Anjali and Konstantin are in line at Starbucks. Konstantin orders a latte and the server asks whether he would prefer soy milk or whole milk. Konstantin hesitates for a moment, then chooses soy. Suddenly, Anjali grips his hand intensely and remarks:

“After such a latte, the only choice left is the muzzle of a pistol or the foot of the cross.”

She gazes into his eyes sternly, then leaves, even though they had made plans to study topological vector spaces together.

Konstantin feels a deep existential unease. Later, he checks Anjali’s Instagram stories and discovers she had Huysmans Rolled him! He feels silly for briefly considering cutting back on anal sex in order to attend a Latin Mass.

EXAMPLE 2: Levi arrives at the gathering wearing an offensive T-shirt advertising corporate ‘rock’ music band The Rolling Stones. Carlos asks him where he bought it.

“UNIQLO.”

Carlos spits in Levi’s face and remarks, “After such a UNIQLO purchase, the only choice left is the muzzle of a pistol or the foot of the cross.”

Levi tentatively starts Googling Cistercian monasteries until Carlos smacks the phone out of his hand and explains that Bernard of Clairvaux was a rank sucker. Chastened, Levi mends his ways and learns about Maimi’s brand KOBINAI.

“Huysmans Rolled

— Dan Briskin

art by Aaron Lange

It’s tough to judge the sincerity of another person’s religious conversion. I agree with you that Huysmans was a serious man who arrived there after for protracted study, and self-examination. I read Against the Grain as an undergraduate over 40 years ago. It was a milestone on my return to the Catholic faith. I did not experience a flip. It was a slow process, with backsliding. It’s interesting that JKH remains relevant as a symbol and an example of conversion. Much about the current world is so putrid that people recoil from it. Some of them will turn to religion. Some of them will be serious about that turn. Some of them will persevere with it. The years ahead will be interesting. I’m going to take a walk and pray the Rosary, and visit the Eucharistic chapel at the Catholic church near where I live. Someone I knew over 50 years ago committed suicide yesterday, and I just heard about it. There will never be a shortage of lost souls to pray for.

And as always, great art by Aaron. We're lucky to have the contributing artists that we do