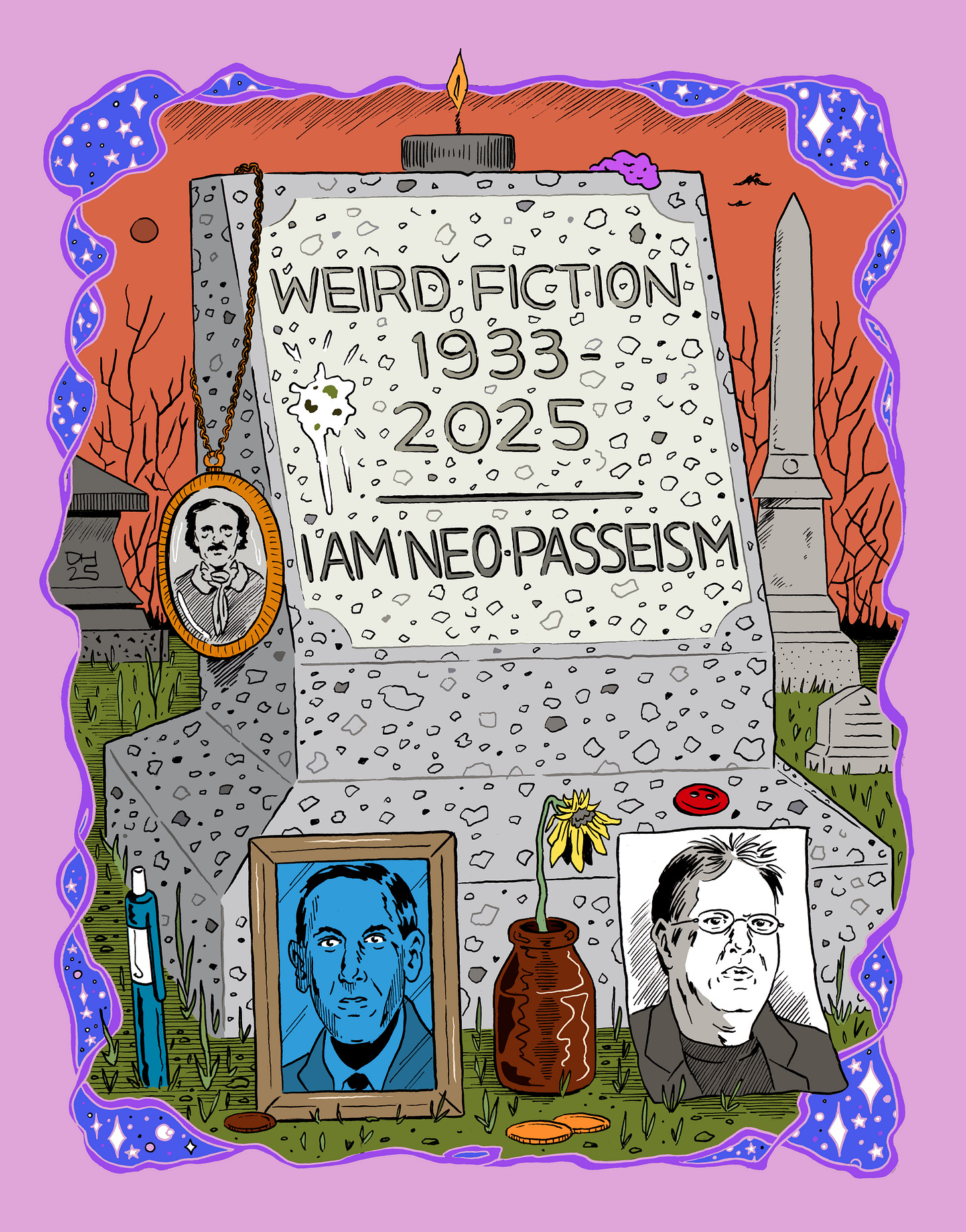

by Colby Smith

I have seen no more poignant a testament to the status of contemporary weird fiction than, when I visited Providence, Rhode Island in the summer of 2017, there were cheap trinkets framed as “tributes” scattered across Lovecraft’s headstone (at once telling of the destitution he endured in his final years and bearing the imposing epitaph I AM PROVIDENCE) that would in any other context be called litter or trash.

Such sights are diagnostic symptoms of the disease of fandom; and, more latently, of the illegitimacy of the weird fiction marketing scheme itself.

”Weird Fiction”—as immediately associated with the parameters set forth by Lovecraft and his protégés published in Weird Tales—was born with this disease, which is evidently incurable. Although the term has amassed a regular cornucopia of scholarship and commentary, coherent definitions get muddier and more ambiguous with time and context. Some critics emphasize that the content of the weird tale is the deciding factor: the “weirder”, the “purer”. Others emphasize the visceral sensations that a “weird tale” elicits in the reader: usually some variation of disquieting awe.

In a brief essay titled “Notes on Writing Weird Fiction”, which Lovecraft wrote in 1933, he outlines his conception of the ideal weird tale and describes his general praxis for composing his own weird tales. On his attraction towards weird stories and their intended effects he writes:

I choose weird stories because they suit my inclination best—one of my strongest and most persistent wishes being to achieve, momentarily, the illusion of some strange suspension or violation of the galling limitations of time, space, and natural law which for ever [sic] imprison us and frustrate our curiosity about the infinite cosmic spaces beyond the radius of our sight and analysis. These stories frequently emphasise [sic] the element of horror because fear is our deepest and strongest emotion, and the one which best lends itself to the creation of nature-defying illusions. Horror and the unknown or the strange are always closely connected, so that it is hard to create a convincing picture of shattered natural law or cosmic alienage or ‘outsideness’ without laying stress on the emotion of fear.

By this time Lovecraft had completed the majority of his canonical masterpieces, especially those which most closely corroborate his conception of the ideal weird tale, such as “The Call of Cthulhu”, “The Colour Out of Space” (his most accomplished tale generally, let alone in this respect), “At the Mountains of Madness,” and “The Dunwich Horror.” They were tales that signified the vision of, as Fritz Leiber dubbed him, a literary Copernicus. But, even among the many who were intimately part of Lovecraft’s circle and as such could know his views on such things more than editors or his abhorred society, fandom forced them to remain literary Ptolemies.

S.T. Joshi (widely considered the biographical and critical authority on Lovecraft), who, after delivering a soliloquy of fandom, boycotted the World Fantasy Award and returned his own trophies to the Convention after the widely-publicized retirement of the Gahan Wilson bust, published an academic study of the development of weird fiction titled The Weird Tale (Wildside Press, LLC, 1990). In his introduction, he is considerably cautious about defining “weird fiction,” justifiably proposing that any comprehensive definition of the term may be functionally impossible after Lovecraft:

Recent work in this field has caused an irremediable confusion of terms such as horror, terror, the supernatural, fantasy, the fantastic, ghost story, Gothic fiction, and others. It does not appear that any single critic’s usage even approximates that of any other, and no definition of the weird tale embraces all types of works that can plausibly be assumed to enter into the scope of the term. This difficulty is a direct result of the conception of the weird tale as some well-defined genre to which some works ‘belong’ and others do not.

He then logically restricts his use of the term “weird tale,” as Lovecraft did in “Notes…,” to focus on achieved sensations rather than parameters of content. Joshi correctly believes that “weird fiction” is a constantly torn and punctured umbrella term for the Gothic, horror, fantasy, etc. While it is true that the writers that he surveys in The Weird Tale (besides Lovecraft, there is the usual rogue’s gallery comprising Algernon Blackwood, M.R. James, Ambrose Bierce, and others) are lumped de facto into the “horror” tradition, they are the other planets of Lovecraft’s personal heliocentric system; and, as such, impossible to totally divorce from Lovecraftian fiction.

As many purveyors of weird fiction, especially purist fans, reflexively take Lovecraft’s word on the subject, like evangelical Christians giving sole credence to the King James translation of their Bible, they predictably turn to the guidance of HPL’s landmark critical essay “Supernatural Horror in Literature”, then laud Edgar Allan Poe as the fundamental progenitor of the weird tale.

Edgar Allan Poe is undoubtedly the most influential American writer. The pan-cultural dialogue surrounding Poe’s work (though characterized by some common trajectories which in themselves were subjected to literary genetic drift in large part due to a renaissance of translation from the mid-20th century onward) was never uniform. Poe signaled the paradigm shift between the Romantic and Symbolist movements; Symbolism itself was the nexus between Romanticism, Modernism, and every adjacent avant-garde movement of the 20th century. If Poe had never existed, a Poe must by necessity be deterministically generated to prevent an alternate timeline for modern literature. Poe, alongside his Symbolist heirs and in complimentary measure Zola-influenced Naturalist writing, was especially critical for the advent of Modernist movements outside of the Anglosphere; he permanently influenced Japanese letters from the Meiji Era onward, from the ground-zero short fiction of Ryūnosuke Akutagawa to the ero-guro nonsense and Poe-esque mystery pieces of Edogawa Rampo. The same must be said of Latin American Modernism, with formative writers such as Horacio Quiroga and Leopoldo Lugones, as well as the ubiquitously lauded Jorge Luis Borges and Juan Rulfo being impressive heirs.

Assembling a unified, taxonomical canon centered around Poe can only be so useful when its expansion and revision is applied to the weird fiction tradition. Poe’s impact on modern literature (whether squarely avant-garde, broadly fantastic or speculative, or literature featuring more prominent and straightforward genre tropes) is not wholly congruent, nor is it is wholly diametrical; yet reductively calling Poe’s work weird fiction is as useful as labeling the Homeric epics fantasy.

Returning to Lovecraft: his reactionary convictions extended to poetry as well. He believed, for instance, that Alexander Pope was the last great poet and, appropriately enough for an early Hitler sympathizer, disdained Modernism broadly, viewing it as evidence of the decline of Anglo-Saxon culture; yet he, too, was indebted to the Symbolist and Decadent movements. He was impressed by Baudelaire, even quoting the posthumously-published fragment “Rockets” for the epigraph of his story “Hypnos.” Lovecraft had also read and admired The Book of Jade, American Decadent poet David Park Barnitz’s sole volume of verse, published shortly before his suicide at a tragically young age. Robert W. Chambers’ only widely-remembered and influential volume, The King in Yellow, was Lovecraft’s greatest influence from the Decadent tradition. He heaped considerable praise on The King in Yellow in “Supernatural Horror in Literature”; and, consequently, it is near-universally classified as a critical work in the weird fiction canon rather than an otherwise squarely Yellow Nineties work. The great Arthur Machen was, at the core, a Decadent writer, too. So it is bizarre, and certainly convenient, that critics are more battle-ready when it comes to ignoring the Decadent movement, despite all evidence from every angle that Decadence is indispensable to the weird tale.

The conceptual development of the Lovecraftian weird tale, usually synonymous with cosmic horror, effectively terminated with the fiction of Thomas Ligotti and his demiurge-wrought, cannibalistic existence that grants no solace except to the unborn. The mechanisms of Ligotti’s universe govern his fiction on both the macro- and micro- levels. Anthropocentric inclinations such as the bureaucratic and representative democratic organization (such as in “The Town Manager”) as well as industrial-to-late capitalism (such as in “The Red Tower”), are functionally and metaphysically indistinguishable from tales concerned with his traditional cosmic horror fiction (such as “Vastarien”). After Ligotti, the only options for the Lovecraftian weird tale are to:

a) appeal to a more predictable Manichean cosmos;

b) attempt, and usually fail, to elevate Weird Tales-era and other pulp kitsch tropes into literature;

c) revert to the traditional ghost story;

d) faux-Surrealism;

e) “folk-horror”;

f) material that would be more appropriate to simply label fantasy or science fiction, etc.

Would it be anything but ill-advised to broaden the scope of the diagnostic characteristics of a supposed genre if they were already obscure, seemingly to the point of no return nearly thirty-five years ago, or arguably before then, let alone declare a New Weird at all?

Jeff VanderMeer has labelled the Homeric epics “fantasy,” but—analogously with Poe—in service to his piloting of the contemporary discourse of what constitutes weird fiction. VanderMeer, in an op-ed titled “The Uncanny Power of Weird Fiction” published in The Atlantic in 2014, conflates (under the guise of clarification or redefining) weird fiction with “the uncanny”. VanderMeer describes weird fiction as “[a] country with no border, found in the spaces between.” The “uncanny” which VanderMeer touts as central to weird fiction is misappropriated from the more impartial lineage of the term. Freud outlined this phenomenon in his 1919 essay, “The ‘Uncanny’.” Freud’s conception of the uncanny, derived from the German unheimlich and cross-referenced with similar words in other languages, is the familiar-but-foreign. Like Lovecraft’s conception of the ideal weird tale, Freud’s conception of the uncanny is fundamentally horrific. This horror rests in the familiar being compromised by the foreign—not just how the familiar is compromised, but also the consequences of such compromise. Freud’s uncanny lies on the cusp of Lovecraft’s unknown. Such close proximity between Freud’s uncanny and Lovecraft’s unknown is likely the root of VanderMeer’s confusion and misdiagnosis of the uncanny.

VanderMeer’s interpretation of the uncanny allows for weird fiction to display corrupted wholesomeness, breaking the levee against shoehorned comradery with fairy tales and fables, whether with traditional examples by Aesop and Jean de La Fontaine or more modern, socially-conscious interpretations like Angela Carter’s, and potentially any work of speculative fiction that isn’t conservative, conformist, cowardly, or even reactionary in its mode of genre-expression. His prescriptivist view of weird fiction, at its most optimistic, corrodes meaningful distinctions of weird fiction as an art form even further.

In 2011, Macmillan published a doorstop anthology edited by VanderMeer and his wife Ann entitled The Weird: A Compendium of Strange and Dark Stories. According to Locus, it is likely the largest and, for its page-count and range, most ambitious anthology of speculative fiction in existence, even after thirteen years in print, surpassing the Dangerous Visions duology edited by Harlan Ellison. Once more, the fundamental criterion for the pieces the VanderMeers selected, described in the introduction, is that of The Weird conveying “a sensation—one of terror and wonder”; again, the misappropriation of the uncanny. The majority of the works selected for the anthology are squarely or at least tangentially in line with Lovecraft’s framework for the weird tale, even non-Anglophone stories (though more fittingly called macabre) such as Gustav Meyrink’s “The Man in the Bottle,” Stefan Grabinski’s “The White Weyrak,” Hanns Heinz Ewers’ “The Spider,” and an excerpt from Alfred Kubin’s only novel The Other Side. It is critical to acknowledge that the above pieces are products of Poe’s influence across continental Europe.

Yet there is a minority of works that have no business being included, especially in light of Poe’s influence after French Symbolism.

The authors therein that have nothing to do with weird fiction whatsoever are, naturally, non-Anglophone and unconditionally Modernist. These include, for instance, Akutagawa, Bengali thinker and activist Rabindranath Tagore, Bruno Schulz, Jorge Luis Borges, the postwar Italian fabulist Dino Buzzati, the Japanese poet Hagiwara Sakutaro, Kafka, and the Nigerian novelist Amos Tutuola. While VanderMeer ought to be credited for commissioning original translations of the likes of Akutagawa and Cortázar, and for demonstrating his dedication to the progression of The Weird, it is the inclusion of these authors and the reduction of their visions to a genre scheme that has rendered further revision of the canon an exercise in paper-thin integrity. Take a wild guess why it was attempted—for profit ($$$)!

This is grasping at straws at best and cultural appropriation at worst.

The only cure for weird fiction’s numerous diseases is to sincerely venture beyond the influence of Lovecraft, instead of favoring mere recently-vogue, morally-updated subversions of his tropes, which are parasitically-indebted to the originals, no matter how critical of the source material and of the gentleman from Providence they claim to be…while cracking down on the unwarranted, VanderMeer-style press-ganging of works that have little or nothing to do with weird fiction. This will necessitate, eventually, the disavowal of weird fiction altogether.

The hopefully-impending paradigm shift will be lower stakes than, for instance, the New Wave of science fiction, which the more interesting and legitimate examples of allegedly weird fiction are irrevocably indebted to, such as selected works by Michael Cisco; but even reform must begin with the phrase post-Lovecraft.

Pastiche-hauntology, circular influences, and vapid, MFA/workshop-fertilized work predestined to be “dazzling” bestsellers and win institutionalized accolades—the Raytheon-sponsored Hugos can never wash the literal blood from their hands—fundamentally hinders a post-Lovecraft landscape and must be disowned and excommunicated. Although transcending Ligotti’s existential framework is almost certainly impossible, the a’s, b’s, etc. outlined above must remain sincere and interesting. A basic example would be, instead of faux-Surrealism, works that can be called Surreal in both praxis and spirit.

It would be misguided, however, to define “post-Lovecraft” as simply a reaction against Lovecraft. This is as erroneous, in our view, as considering post-Tolkien fantasy a mere reaction against Tolkien. Fantasy as a coherent art-form existed before and after The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, and numerous works of serious fantasy after Tolkien were written independently of Tolkien-esque fantasy while disregarding him as an obvious influence at all.

The corpus of the contemporary British writer Quentin S. Crisp—and, guilty by association, many central texts of the Neo-Decadent movement—are a starting point of what post-Lovecraftian fiction can, and should, resemble. Much of Crisp’s early short fiction, namely in his collections Morbid Tales and Rule Dementia!, is more colored by traditional strains of weird fiction, especially the British ghost story tradition and, perhaps most prominently, Robert Aickman. As Crisp’s fiction matured, however, it became informed by the aesthetics and conventions of Japanese literature; this influence was instilled by Crisp attending Kyoto University around the turn of the century. He has consistently cited Nagai Kafū, a Modernist whose work owes its greatest debt to French Naturalism, to the extent that Kafū translated works by Zola into Japanese. Notable examples from Crisp include the I-novel-esque novella Shrike and his chapbooks of English-approximated tanka poetry, September and October. These influences are also apparent in his works that can be most appropriately termed science-fiction, such as the novella Blue on Blue and the story “Karakasa” in All God’s Angels, Beware! Crisp’s influences cannot so readily be called cultural appropriation because of his infinite/intimate familiarity with Japanese culture and literature, and his work is, more obviously, conscious homage. There are essentially no other contemporary writers, as far as the author is aware, that can be correctly placed under the tattered weird fiction umbrella than Quentin S. Crisp.

Such genuinely eccentric work that has miniscule interest in perpetuating conventions is mandatory for the advent of post-weird literature.

art by Dan Heyer