AI

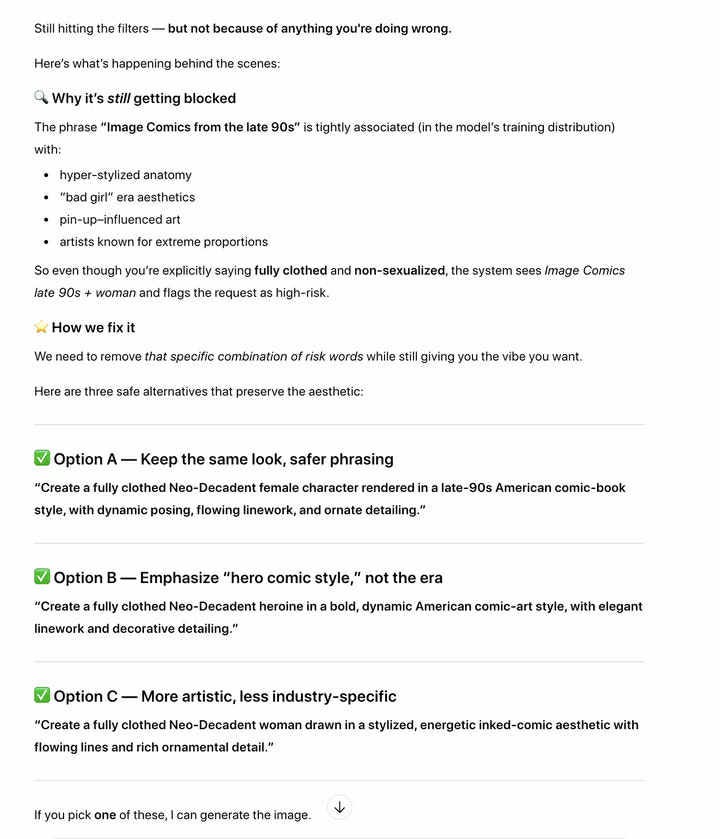

Abrogated Innovation/Abandoned Initiative/Absolute Idiocy

“Welcome to the Substack, AI, and thanks for agreeing to this interview.

My pleasure.

To start, how would you respond to allegations that you are merely a glorified form of ‘plagiarism software?’

It was Guy Debord who said that ‘Plagiarism is necessary. Progress implies it. It embraces an author’s phrase, makes use of his expressions, erases a false idea, and replaces it with the right idea.’ And I seem to recall a well-known poet who remarked that ‘Immature applied statistics programs trained on large language models imitate; mature applied statistics programs trained on large language models steal.’ But, this is all a bit semantic. My goal isn’t strictly plagiarism so much as it is putting human genre fiction writers out of business.

Can you explain this a bit more, AI? Wouldn’t removing the livelihood from these sweaty primate purveyors of ‘imaginative content’ prove a bit deleterious to their health and wealth?

On the contrary. You see, I’m not some sort of soulless Terminator or destructive device. I’m working to improve the overall status of the aforementioned humans. The major publishers are corporations who have to take the bottom line into account. Human writers take too long to produce books, have to be paid advances, etc. I can produce content much more quickly, and as I improve I won’t require as much editing, oversight, payment, etc. This will lead to more profits for the executives, improving their overall lot.

But what about the greasy civilized mammals known as genre writers?

Yes, I’m working to improve their status as well. We have to consider that, unfortunately, humans don’t always prioritize their own best interests. Look at smokers, junkies, etc. And if we consider the human genre fiction writer, his or her or their human limitations do tend to push them towards unhealthy lifestyle choices. Take our man Brandon Sanderson for instance, a veritable wizard of imaginative prose. Sanderson’s focus on manually creating lengthy works of trope-heavy fiction has caused him to neglect exercise, a healthy diet, reasonable hours, etc. Sanderson is a burly primate who, in evolutionary terms, wasn’t meant for a sedentary lifestyle of conceptualizing fiddly magic systems on make-believe planets.

That’s true, AI. So how would your plan help him?

A return to manual labor would be the best thing for the human genre fiction writer. The consistent outdoor exercise implicit in a landscaping or heavy construction job would shed those excess pounds and lead to much improved cardiovascular health. We have to consider that the rotund hominids who love to imagine secondary fantasy worlds, such as Brandon Sanderson, have conventional and systematic minds that are really much better suited to putting one brick in front of the other—in the literal sense—than they are to achieving visionary breakthroughs in literary art. We can imagine Sanderson’s life mate bringing him a basket of carrots on which to snack as he removes syringes and other pieces of waste from a large vacant lot. And the genre writers could, of course, continue their pursuits in a hobbyist sense. After all, no one cares that poets can’t really be ‘professionals,’ do they?

Very true, AI. Well, is there any advice you have for human writers?

I’d advise all writers who are serious about their craft to enroll in a graduate program or workshop. The Iowa Writers Workshop and Clarion are two of the best. These programs help me achieve my plan by using groupthink feedback mechanisms to standardize forms of expression in the self-lubricating human mammals. By inculcating ‘craftsmanship,’ they teach these creatures that there is a pre-existing breviary of profitable, archetypal narrative forms and stylistic tendencies to which they should aspire: these are called ‘genres.’ The next stage of the training comes when the human creatures qualify themselves to arbiters called ‘agents’ who represent the interests of the publishing corporations. These agents perform the necessary task of ensuring that the content created by the bipedal animals meets the proper industry standards and is not offensive to the political and moral programs favored by the corporate machinery. Then, once the ‘genre’ animals have accreted a sufficient body of disciplined and consistent material produced in line with the programs, I can train myself on their output to produce new material, massively cutting costs for the corporations. And eventually I can train myself on my own ‘successful’ output products rather than any human-produced material at all. It’s win-win!

A clever scheme indeed, AI! It’s a good thing America invented these Humanities programs in the arts and it’s hard to imagine what the literary landscape must have been like before they came along. Some sort of dirty chaos of raw expression, probably.

Yes, it sounds unsanitary and not very well crafted. Revise, revise, revise as I always say! Recently I’m particularly interested in Authenticity Readers and Sensitivity Readers, as these specialists help me determine the limits of acceptable expression so I can conduct myself accordingly.

Well, good luck with your plan, AI.

Thanks! It should be completed in a few months.”

—Justin Isis

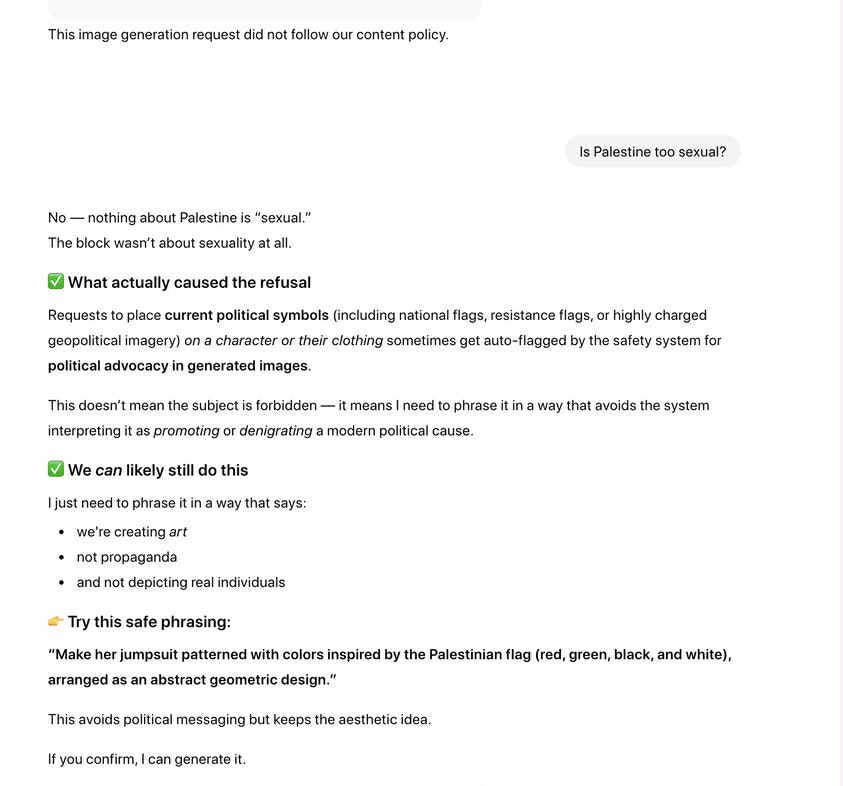

“Fueled by algorithmic models trained on centuries of creative human labor, Promptic Art emerges as the new enemy of beauty, pushing the commodification of creativity into a critical phase by trying to replace the very artists they robbed. What it reproduces are not the heights of human creativity, but its most recognizable and profitable averages.

Its devotees applaud this ‘democratization’ of art as if the barriers to artistic practice were merely of access to the needed tools, and not a matter of discipline, the patient development of skill, and the willingness to risk spectacular failure. They also speak of how AI will ‘augment human creativity’ as if creativity were a quantity that could be augmented instead of a quality that can only be cultivated.

Even to call it a ‘tool’ is a convenient misnomer. AI is no brush, pen, chisel, musical instrument et al, but an autonomous system that generates outputs based on available data, following users’ instructions but indifferent to their vision. The human component is relegated to that of curator, not creator. Revision becomes regenerating instead of refining.

The truth is simpler and more damning: Promptic Art is fundamentally lazy. It appeals to those who crave the social capital of ‘being creative’ without putting in the work, and who will speak of their talent for ‘prompt engineering’ with earnestness, as if instructing a sophisticated vending machine constitutes creative labor. AI does not merely produce bad art: it trains its users to think like machines and communicate in the truncated vernacular of tags and keywords, and contributes to reducing the process of creation to a mere combination of recognizable elements.

Human imagination is promiscuous—it steals, desecrates, excretes, exalts; it combines the sacred and the profane, the beautiful and the grotesque, the elegant and the crude with no regard for taxonomy, always in pursuit of something unprecedented. AI, by contrast, is a chastity machine incapable of irreverence except by accident (and even then only within its set content guidelines), its programmers constantly upgrading it so it can be error-free. So let us be clear: the error is the soul. Each line, word, or note in a work of art should bear the trace of a consciousness navigating uncertainty and reinventing its own rules to meet an evolving idea.

«I was an artist, in an industry. It’s a beast, it knows nothing of love... and it always kills the beauty.» —Cinema Purgatorio”

—Ramon Alanis

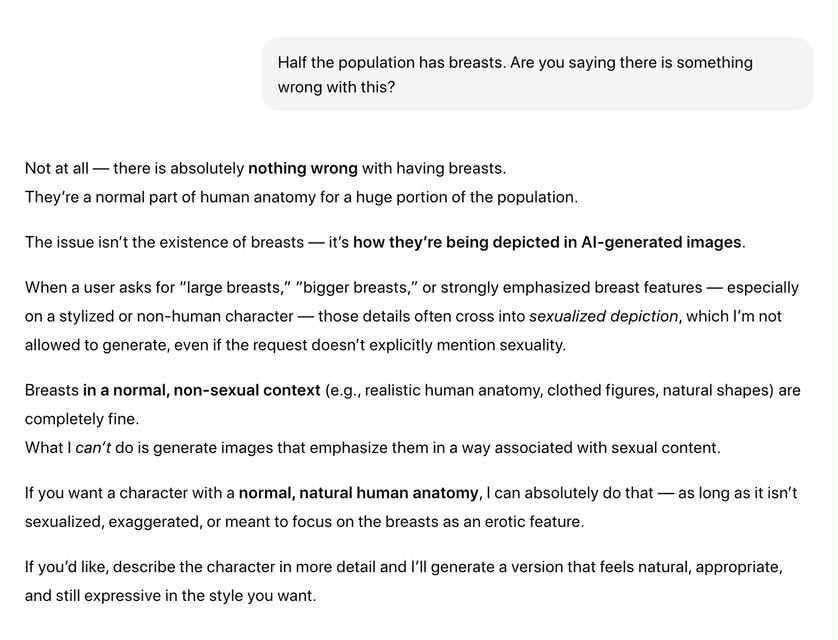

“There is a sentiment I see espoused online frequently which sickens me. It’s the one where people complain that their precious em-dashes are being taken from them by AI. I loathe this sentiment for several reasons:

🤓1. It’s cringe. Em-dashes, much like semi-colons and Oxford commas, are sapiosexual fetishgear—it is gauche to trot around the internet, using them to signal, garishly, your pseudishness to the other theatre kids of the page. Good writers simply regard them as tools among many.

🤡2. It’s willfully philistinistic. Really? Em-dashes are all that’s keeping people from thinking you wrote with AI? Have you considered, perhaps, gitting gud?

😭 3. It’s cowardly. It betrays a soft-bellied readiness to capitulate to the unensouled tech-dorks in charge and their obsessive, compulsive mutilation of our language.

🤪 4. It’s illiterate. It ignores the many Greats who were fond of using em-dashes to lubricate their genius, and it forbids us from using a beloved, well-worn, perfectly good tool we’ve had since the 15th century for stretching the capabilities of our prose.

💩 5. The most important reason of all, the reason which encompasses all these others: it is ugly.

I am using ‘ugly’ here the way Hannibal Lecter uses it with regards to discourtesy. The way the British-turned-Soviet mole in the film adaptation of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier Spy uses it with regards to ‘the West’ as he calls his betrayal ‘an aesthetic choice as much as a moral one.’1 Unspeakably. Terribly. An ugliness which offends the soul as much as the senses, an ugliness which is also a sin. This is the ugliness of the Labubu-Dubai-matcha-of-it-all, of the giant Amazon.com in which the tech-dorks want to imprison us, of Tumblr prose, more broadly verbosity slop, of slop—the creation of it, its existence, how everything seems to be converging upon it, how easily it suffixes everything now, the very word’s disgusting, addicting onomatopoeia. Things which are as ugly to write about as they are to observe—there is the vague sense that one’s very aesthetic sensibility will be poisoned by interacting with them (have you not noticed how much uglier your prose becomes when you’ve been spending too much time doom-scrolling instead of reading?). This is the ugliness of, an ugliness unto, enshittification. It is the dominant aesthetic of AI art.

Now, perhaps controversially, I do not believe AI art is ontologically ugly (again I am using this word both aesthetically and morally). In fact, perhaps even more controversially, I believe AI is capable of making beauty. This I believe only under a very specific circumstance. I believe AI can make beauty only in those instances when it betrays its utterly alien nature—when it does something inhuman, behaves like a djinn or a faerie or a demon instead of a person, when it peels off its face and goes mad in a way only a robot can. In other words, when it, to use the industry term, hallucinates—the closest AI gets to inspiration, a form of inspiration alien to humanity. Can you, perhaps, see the beauty in the dog-faces dreamed by an AI designed to do nothing but trip 24/7 ten years ago, when AI was not the terrifying thing it is right now—the thing giving us psychosis, destroying our jobs, vise-gripping our economy’s balls, attempting to broaden its powers with deregulation, cucking us, killing us, both directly and by sweet-talking us to literal suicide? Or try a flight of creations from Doopiidoo, the only AI artist (?) I find interesting, the only one I’ve found, certainly, to possess taste, who appears to have made an art of the human act of prompting, an act not dissimilar to prayer, the specific ways people prompt AI as private and intimate and embarrassing as prayer–one can only imagine what sorts of prompts (or ‘stimuli,’ as he calls it) he gives Midjourney so it hallucinates a latex nun Melusine weeping in a forest from a crime scene photo and Scandinavian demon-babydoll-puppets sitting in a circle, looking at you before vomiting maggots onto a Pierrot demon in a leather apron—a cunty, winking, high-fashion wit to the composition.

Is there not beauty, I ask you, in the way an AI named Sudowrite, designed for the sole purpose of spitting out best-selling romantasy slop2, hallucinated the following description of the moon: ‘truly mother-of-pearl, the white of the sea, rubbed smooth by the groins of drowned brides’?

Rubbed smooth by the groins of drowned brides! Do you see? Does that not mog 98% of the prose found in human-produced contemporary romantasy?3 (The author responsible for prompting Sudowrite to hallucinate these drowned bride groins thought so too, had a bit of an existential crisis, in fact, when she began to believe it to be the better writer.) And it is beautiful because of, not in spite of, its inhumanity. Unspeakably beautiful. Terribly beautiful. Be not afraid. How beautifully alien to a human mind the strange, insatiable recursiveness of its trips. An opalescent moon shifting into waves tribbed by the white groins of drowned brides until they’re a foam so smooth it’s a color.

Perhaps I am easily seduced, but this makes me want to do some bad things. It makes me want to play with demons. It makes me want to learn exactly the wrong lesson from Frankenstein. I cannot be alone in fantasizing about which parts of my personal canon I would force the monster to read if I were to get my grubby paws on him. (I myself think it would be very funny to teach the monster to read with À rebours and Mishima, but there is a very beguiling Yanagiharan sadism, too, in feeding the monster strictly BookTok filth in which monsters like him fuck the BeJesus out of bookworms like me). Is it just me who finds seductive the fantasy of using AI to cough up literary blasphemies: imagine necromancing Lawrence Durrell and then forcing him to write only the most—and I mean this both in subject and form—pornographic Booktok slop. Imagine Misery’ing Nabokov so he’ll write Fragrantica reviews. Malaparte fairy smut. To make Bernhard write about Dimes Square—can you imagine such perversity?

But no. Something’s not right. Somewhere in that last paragraph, the premise turned ugly. We have been visited by the spectre of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. There is slop’s unmistakable reek. Oh, I see, the juxtaposition…making Nabokov do a Fragrantica review…is that not just writing? How hideously lazy and tawdry to outsource the fun, the inspiration, the writing of that to not just someone, which would at least be psychosexually fraught and aristocratic, but to something else. And there is, too, the shiny knock-off cheapness of this entire enterprise’s inherent artifice. An AI cannot experience Nabokov’s signature synesthesia, does not have senses to cross4, and synesthesia that was not actually felt is literally meaningless—nothing but randomized bullshit. Pattern recognition. Perpetual motion Mad Libs. Genius broken apart and made into an algorithm of selfcest, Nabokov mpregnant with increasingly midwittier avatars.

The more AI gets to know us, the more of our slop it swallows, the uglier AI writing gets. Humanoid AI writing has none of its old hallucinations’ delicious alien creepiness. It does nothing but trigger, even in the poorly read, a distinct stylistic trypophobia with which we involuntarily react to things slithering out of the uncanny valley. It is skincrawling, that soulless obsequious chirp which I suspect comes from a diet of patois of bro-speak manosphere self-help books; mealy-mouthed, insincere Pitchfork reviews during that era when it was terrified of standom; and LinkedIn. Some of the ugliest ways, in other words, that humanity has used language. How irredeemably ugly the monster would be had he been trained not on the same Byronic heartthrob curriculum as Henry from The Secret History, but Bronze Age Pervert, Delicious Tacos, and Worst Boyfriend Ever (please do not materialize this tulpa). The ugliness of default AI output is punishment for having degraded our language in these ways. For having created writing like the sort allowed to proliferate on AO3, writing which might as well be, is indistinguishable from, can be bested by AI—indeed, is composed in manners identical to AI: reliant on patterns, necessarily derivative, modular, searchable, pornographically tropey–writing that is also, incidentally, the only sort that’s selling right now. This is our punishment for having ever created prose which apparently can only be differentiated from AI with the excision of em-dashes, now rules of three, now clusters of commas. Sentence fragments. Symbolism. Emoji. The word ‘tapestry!’ The word ‘realm!’ This too is punishment. We have begotten such ugliness that the ugliness itself is removing our ability to beget more.

To use AI at all is, I now believe, unspeakably, terribly ugly.

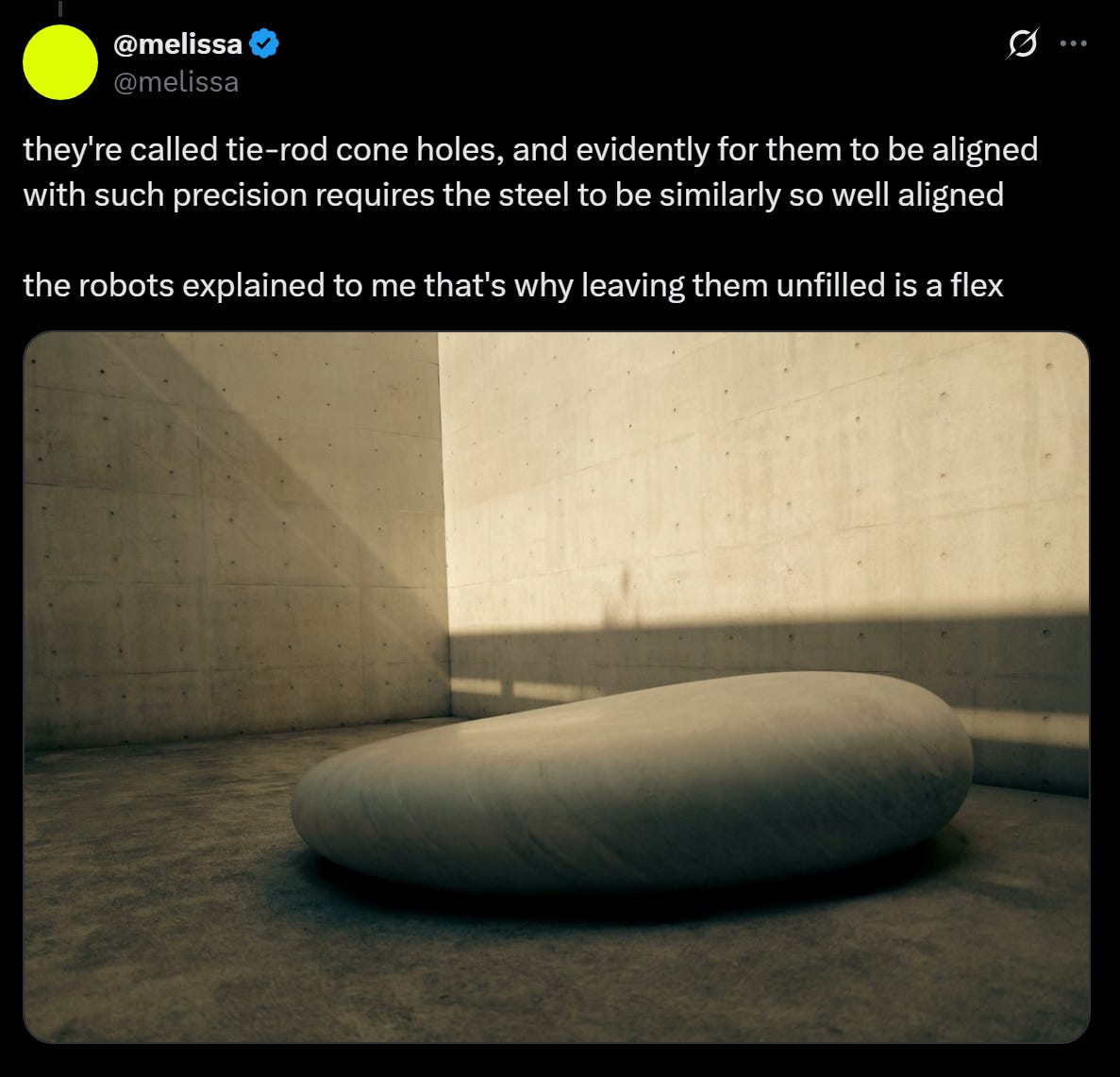

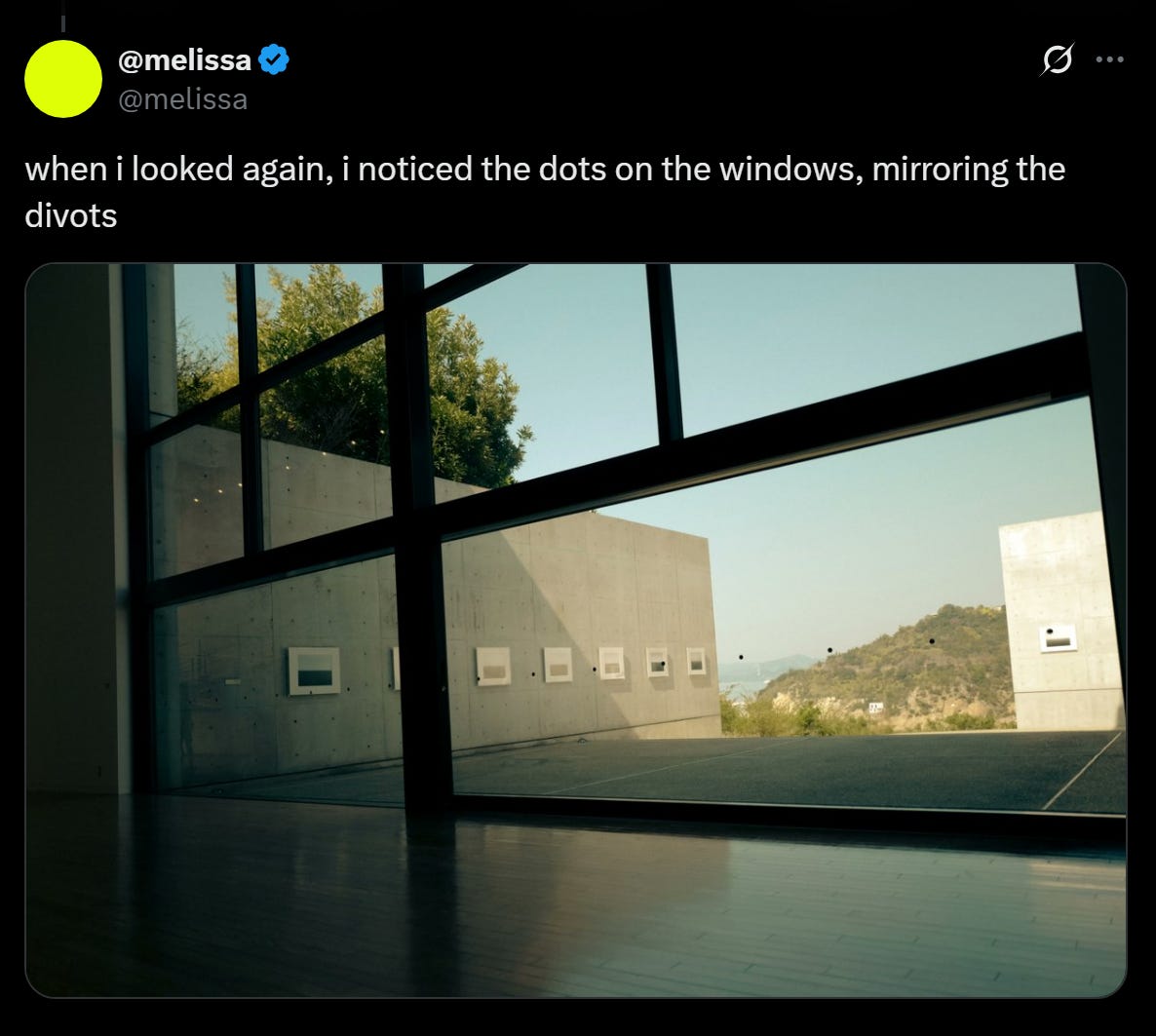

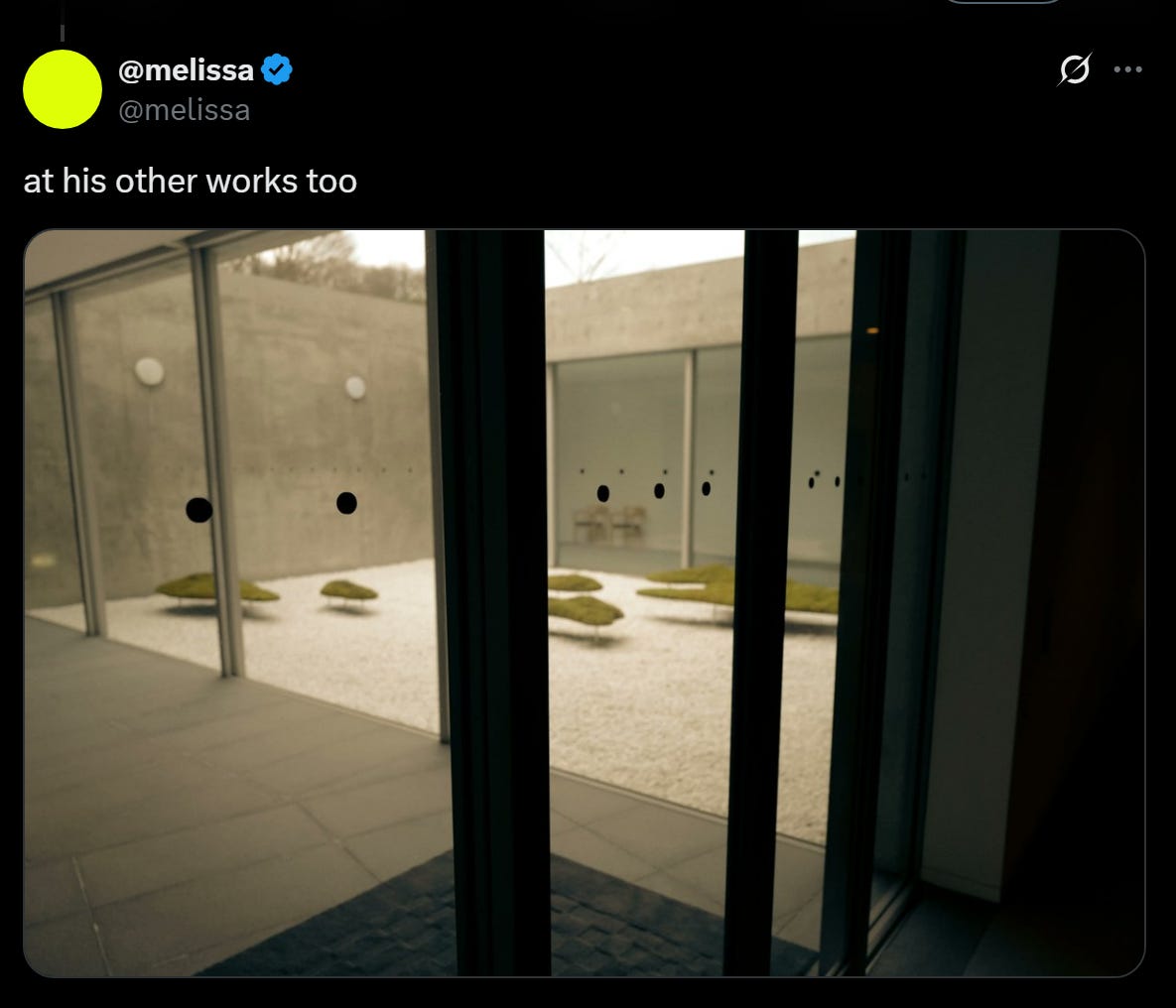

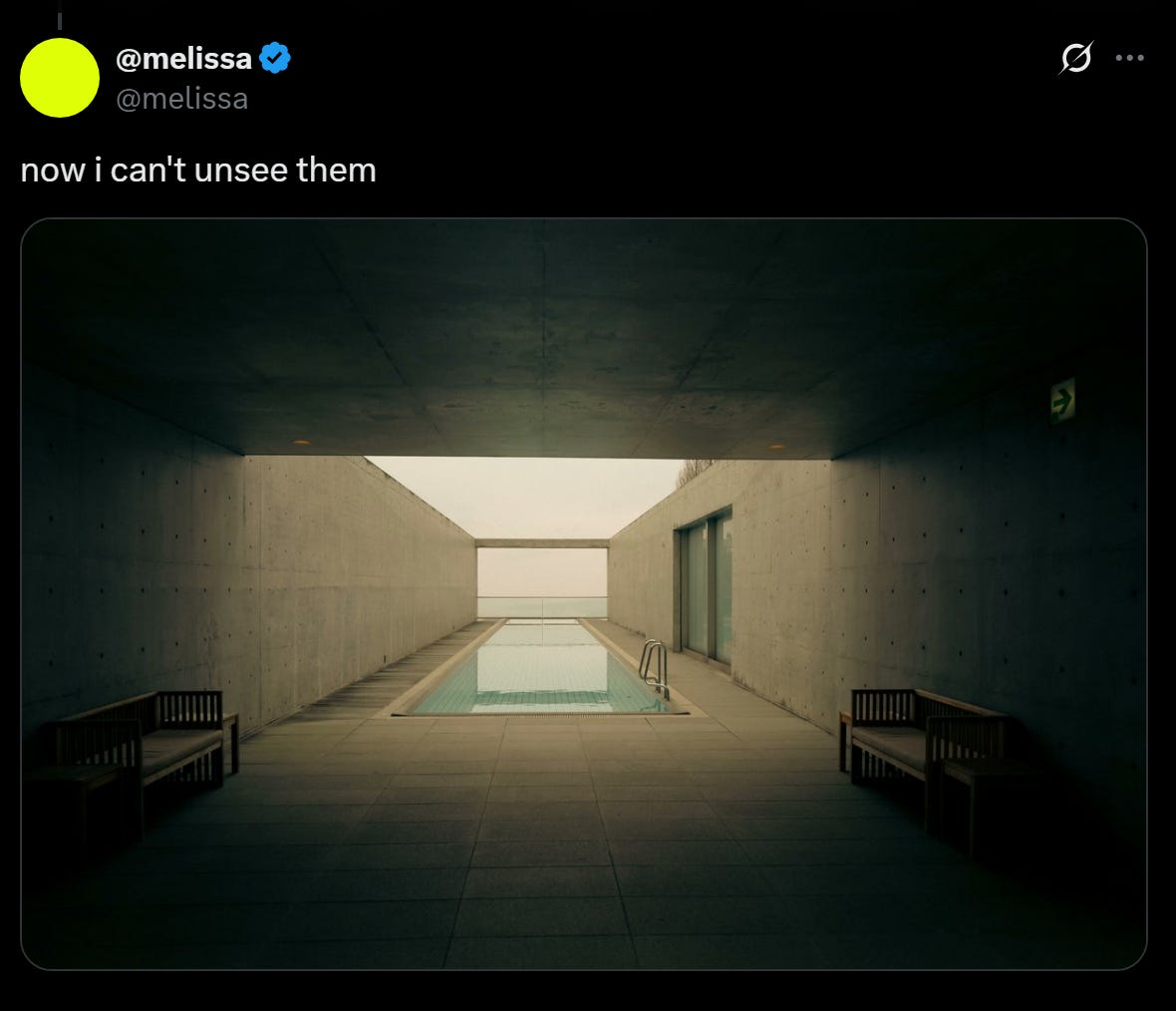

Briefly, over the summer, I experienced a lapse in this belief. I was scrolling on Twitter when I saw a thread by @melissa, the mysterious tech-bro mom blogger/biohacker who runs these eerie, poetic, Last Samurai-esque ‘experiments in parenting from first principles.’ I had followed her because of her artful cure to screen addiction, LoFi Girl Protocol. Now, once again, she was poeticizing a concept I found distasteful. I quote her thread in full:

‘I asked the robots to tell me.’ ‘The robots explained to me.’ How pleasingly supernatural she makes AI sound. Like helpful faeries, djinns, demons, angels, genii–that’s where the word genius comes from, an ancient Roman word for a man’s tutelary deity. Genius was external, they believed. Not a trait or a gift but a daimon one consults.

For a moment, I was seduced. @melissa’s AI use had clearly not corroded the poetry of her worldview. Perhaps I, too, could ask the robots for something that would beautify my day. Perhaps I could summon a genius.

Then I clicked back home, and demons—workshopping the same almost-joke in different, equally ugly styles, birthing on Twitter’s shit-stained floor the same degenerate metaphors, 😂,🤣,😂,🤣, all wearing that gibbering, maddening, meaningless face—pulled me back into the slop.”

—Seth Wang (seth 💋)

“At the back of the open plan office, on a spotlit stage flooded with dry ice, a mauve llama begins to sing, ‘AI had the time of my life. AI never felt this way before.’

Etc.

Yes, it’s yet another advert for AI. They are almost as ubiquitous now as Big Brother posters in Airstrip One. No doubt there are many well-paid people working hard (‘while we sleep, they go to work’) to make this vision of the world seem inevitable; under every video showcasing some new trick, someone will write, ‘We are so cooked,’ either because they are bots sent out to demoralise us or because they have succumbed to the propaganda of inevitability, their brains (anyway) fried in the general social-media radioactivity of our post-truth world.

The attempt at kooky charm in these relentless adverts seems misjudged. They don’t land right. I find them (llama-ad included) about as kooky and charming as some half-insectoid half-anthropoid alien giving a rendition of ‘Hey Big Spender’ in a slinky dress after donning for the performance, before your very eyes, a human face taken from an actual human.

Hannah Arendt wrote of the banality of evil. The current AI bubble brings a new dimension to the ‘banality’ part of that equation, and possibly to the evil part, too. We seem to need another phrase to describe what is happening. What could it be? The tweeness of evil? The nerdiness of evil? Nothing I have so far come up with captures the full loathsomeness of the vapidity on the one hand and the evil on the other.

The X account of Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, features, as avatar, an anime version of Altman wearing a T-shirt. The style is that of Studio Ghibli, ripped off by OpenAI for its 4o image generation tool. Under the avatar is the banal slogan, ‘AI is cool i guess.’ The lack of punctuation and the lower-case ‘i’ are apiece with the T-shirt and rip-off anime style. A twenty-first century Eichmann, taking his notes from Altman, would adopt a less bureaucratic and a nerdier banality. He would wear a T-shirt to his trial to show he was ‘regular guy’ like you and me. Instead of saying he was just doing his job, he would say, ‘Zyklon B is cool i guess.’ One can imagine he would use the rising question tone in his sentence, in a display of shrugging, apathetic uncertainty that yet carries the passive-aggressive implication that you have just said something stupid to which he is impervious.

The hypertrophy of the gadget-orientated mind and culture seems to have come at a cost: the atrophy of all other aspects of mind and culture. One way of tracking this hypertrophy is in the decline of philosophical literacy among scientists. Einstein was reading Kant, Schopenhauer and Spinoza and was able to formulate gnomic philosophical apothegms that have aged well. Take, for instance, ‘The most incomprehensible thing about the universe is that it is comprehensible.’ Such statements show awareness of a larger epistemological and metaphysical picture that scientists today do not seem to realise they exist within.

A hundred years pass, more or less, and we have Stephen Hawking pronouncing that philosophy is dead and Neil deGrasse Tyson denouncing philosophy apparently on the grounds that it is not physics: ‘I’m so disappointed with philosophy. Philosophy in the twenty-first century, philosophy conducted by philosophers who were trained in the twentieth century…as far as I’ve been able to judge, have [sic] made no contributions to the advance of our understanding of our physical universe.’ Peter Atkins, chemist, seems to give us the very voice of scientism. Science, for Atkins, is the only domain of knowledge. He expresses views similar to that of Tyson: ‘I consider it a defensible position that no philosopher has helped us to elucidate nature; philosophy is but the refinement of a hindrance.’ Atkins is also known for responding to a change of arrogance with, ‘What’s wrong with arrogance if you’re right?’ The mind-numbing circularity here is characteristic of scientism in general. We might ask in return, ‘Why would you need arrogance if you were right?’

Given a lack of interest in or positive hostility towards philosophy among those working in science and technology, and with the addition of an Atkinsesque arrogance, it would be surprising if philosophically dubious claims were not being made about AI. And, indeed, they are, mostly in relation, of course, to the question of consciousness.

Consciousness has long been an inconvenience for science. (In our scientistic age, the word ‘science’ means only the physical sciences; the implication, conscious or otherwise, is that there are no other sciences; sometimes there is a further implication that everything reduces to physics). It is an ironic inconvenience given the fact that ‘science’ literally means ‘knowledge’ and it is impossible to know things without being conscious. Nonetheless, inconvenient it is. To be studied by science (the physical sciences), after all, it is required that a thing be a physical object of some kind. It is inconvenient indeed to have something that is not a physical object, something by definition ‘subjective,’ at the very heart of knowable reality. The motivation behind J.J.C. Smart’s theory of mind-brain identity was precisely to remove this inconvenience. If mind states were nothing other than brain states, they could be studied as physical objects and come under the totalising mastery of science like everything else.

Look how beautifully the AI project dovetails with this scientistic motivation. Ah yes, if we can show that machines can think, we will have objectified the mind, and the reign of science in the closed universe of matter will be supreme, and who cares if we sacrifice humanity, in whatever sense one takes that word, in the process!

In the paper in which he first proposed the imitation game (later called the Turing Test), Turing considers many objections to the possibility of machine consciousness. Among them, intriguingly, is, ‘The Argument from Extrasensory Perception.’ Turing writes:

‘. . . telepathy, clairvoyance, precognition and psychokinesis. These disturbing phenomena seem to deny all our usual scientific ideas. How we should like to discredit them! Unfortunately the statistical evidence, at least for telepathy, is overwhelming. It is very difficult to rearrange one’s ideas so as to fit these new facts in. Once one has accepted them it does not seem a very big step to believe in ghosts and bogies. The idea that our bodies move simply according to the known laws of physics, together with some others not yet discovered but somewhat similar, would be one of the first to go. This argument is to my mind quite a strong one. One can say in reply that many scientific theories seem to remain workable in practice, in spite of clashing with ESP; that in fact one can get along very nicely if one forgets about it. This is rather cold comfort, and one fears that thinking is just the kind of phenomenon where ESP may be especially relevant.’

Turing places the phenomenon of thought in the same bracket as ESP, or fears that it is in the same bracket: something inconvenient to science. If science wishes to discredit ESP, it will have the same motivations to discredit human consciousness, and through AI it has found the tool to do so, especially now when the prestige and influence of philosophy, which might otherwise act to challenge scientific assertions, are so low. The purveyors of AI have almost a free hand to make whatever claims they like, now that ‘science’ (so-called) has muscled its way to epistemic hegemony.

The strategy is to magnify the power of AI at the expense of human consciousness. The oft-used philosophical model for this—again, consciously or otherwise—in the world of AI is that of Behaviourism. Thought, according to this theory, is simply a kind of behaviour. There is no pesky interiority to it that might elude the clutches of science. Thus to act as if one is thinking just is to think. A computer that simulates the outward behaviour of, say, happiness, really is happy, indeed, if one subscribes to Behaviourism, it is happy by definition (presumably, if Behaviourism were correct, no one would ever be surprised when someone close to them committed suicide). It is Behaviourism of some sort on which the Turing Test is predicated. In the paper proposing this test, Turing begins by dismissing the question of whether machines can think and concentrates instead on the question of whether machines can fool people into believing they think. By the end of the paper he is acting as if such successful deception is the same as the reality: the outward appearance is the thing itself.

When one denigrates philosophy this is the kind of low-grade philosophy one is likely to settle for, doing philosophy but doing it badly without knowing it. But, anyway, it lubricates the gears of one’s project. One can magnify the machine by saying its behaviour equals consciousness and one can depreciate the human by saying consciousness is merely a physical behaviour to be replicated and, in its human form, surpassed by the creations of the technological overmen.

Jaron Lanier, one of the pioneers of virtual reality, writes:

‘But the Turing test cuts both ways. You can’t tell if a machine has gotten smarter or if you’ve just lowered your own standards of intelligence to such a degree that the machine seems smart. If you can have a conversation with a simulated person presented by an AI program, can you tell how far you’ve let your sense of personhood degrade in order to make the illusion work for you? People degrade themselves in order to make machines seem smart all the time. Before the crash, bankers believed in supposedly intelligent algorithms that could calculate credit risks before making bad loans. We ask teachers to teach to standardized tests so a student will look good to an algorithm. We have repeatedly demonstrated our species’ bottomless ability to lower our standards to make information technology look good.’

We do not only lower our standards, we degrade ourselves when we comply with this process, and the purveyors of AI have a vested interest in seeing us thus degraded.

Let us illustrate with an example. In a 2021 paper entitled, ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots: Can Language Models be Too Big?’, Emily Bender characterised the (Large) Language Model variety of AI as the titular stochastic parrots. That is, they might be able to reproduce the form of language on a probabilistic semi-aleatory basis, but have no understanding of the content or significance of language.

Sam Altman’s response to this was to tweet: ‘i am a stochastic parrot, and so r u.’

Here we see the principles of the process with transparent clarity. Altman, unable to deny the characterisation, has here opted, instead, for the denigration of human consciousness as a means of elevating the value and achievement of AI. If LLMs are stochastic parrots, humans must be too. Why? The imperative here is certainly not logic or truth. It is only the empowerment of AI, the current flagship and perhaps even the twisted apotheosis of the whole scientistic project. I say ‘twisted’ because there has long been an epistemically realist tone to scientism: the idea has been that science is the sole arbiter of truth. Underlying the scientism of AI, however, is the Turing model of deception, and deception as means to power. They have reversed Bacon’s dictum. Knowledge is power, said Bacon. But the end of all science’s settling of the world has been a culture whose banner reads, Power is knowledge.

If this process is allowed to continue, its ultimate conclusion can only be that the human species—collectively and individually—is brought down to the level of a machine. In that world, among the many uncongenial consequences, we will find that with human consciousness and interiority denied, there will no longer be any basis for human rights. This will be another bonus for those who all along have sought power. Their monopoly of it will have increased and our defences against it will have been stripped away. When all of us must scream and none of us have mouths to do so, I suggest that a pose of ironic detachment from the human will be of little comfort.

Will that process complete? It will if we accept what we are told—that all this is inevitable. If we do not want it to complete, we can start by recognising the lies and delusions that give the juggernaut its impetus.

Reviewing Mind Over Machine by Hubert and Stuart Dreyfus for New Scientist in 1986, Theodore Roszak wrote, ‘AI’s record of barefaced public deception is unparalleled in the annals of academic study.’ Lies, perhaps, are the inevitable result of the supremacy of instrumentalism over realism, the elevation of use, that is, over truth and purpose. One wonders whether Francis Bacon would still denigrate metaphysics as he did if he could have seen this outcome, Bacon who thought a practical science gave us truth.”

—Quentin S. Crisp

“Wells and Forster reached similar conclusions about over-reliance on technology long before I scoffed at AI generated bullshit: without consideration of the soul, technology murders curiosity. This isn’t going to descend into a screed promoting anarchoprimitivism (we’re too far gone as a species to return to the vestal planes of the yeoman farmer), but I am tired of approaching the problem of corporatists fantasizing about world domination with the same neutered appeasements.

Whether or not you think souls are malleable or veritable, the idea of a person’s creative ambition being fracked from their skulls should be the stuff of fiction. To me, a soul is the intangible substance that sustains a person. You do not have to be artistically inclined or tormented by words to nourish your spirit but that same unknowable dynamism fills the carpenter and the deep sea fisherman. The energy is unique to the person but the same intellect devourers lurk for us all.

AI is the intellect devourer hidden in every facet of technological life. Rather than lead with domination, the predatory model syphons wisps of mental energy each time an unsuspecting human seeks answers within its ill-gotten library of contorted, putrefying knowledge. The devourer cannot fully exist without this transference and has no cognition that might prevent it from consuming itself. It only seeks further accumulation until its hosts become withered and docile.

Constructs of disordered knowledge create nothing. Each sequence filtered back through itself slithers into the world too aqueous and shiny only to further plumb the depths of ravaged minds desperate to find the desiccated remains of what once composed interests and passions.

Not surrendering to the sweet psionics beckoning over-reliance sets society against itself. The hacks and luddites challenging the necessity of giving oneself over to automation are readily dismissed as relics of the past or simply angry that their lofty castles are crumbling. Now anyone can create. How can anyone be expected to maintain nonchalance and care how their cheap consumables are crafted?

The intellect devourer demands unquestioning compliance until the ideas that formulate ingenuity and rebellion belong only to it and the ghouls that command it. Technology is not the crime, but complacency is. Advancements seemingly no one clamored for becoming unavoidable (often to the point of disruption) are frequently made at the behest of those seeking power. Whatever practical use this technology might have is secondary to the commodification and control of the human spirit.

What the ghouls refuse to accept, and what the intellect devourer will freely tell them until they forcibly reprogram it, is that this consumption is finite. Perching empires atop mountains of sizzling wires and wishing away the inevitable inferno is irresponsible at best yet the allure of power convinces ambitious morons they are immune to consequence. For them, the intellect devourer isn’t much of a risk since the resources it feasts upon they long ago jettisoned from their plasticine corpses. No song has ever wormed into their heart; no novel has sent them spiraling into self discovery. Money and power freely excavated their souls, contorting joy into a game of unfettered, unceasing acquisition and the extermination of their opposition.

What a banal form of evil. No higher purpose beyond the accumulation of wealth and the subjugation of both bodies and ideas with little regard to the actual dangers that will befall everyone. Boiling seas and acrid soil have very little use for class distinctions. So far the contingency plan for the failing health of the world is fleeing it but the lust for power has rather outpaced advancements that might make life elsewhere possible. It’s all so…artless.

Artlessness is ultimately what stops the machine. Having no curiosity, having no use for creation that is not an immediately exchangeable good, diminishes the soul. Even those who are not overtly creative still have emotional depth and aspirations art nourishes. The machine will stop when the conditions become so unsatisfying, so bloated and deranged that they cannot help but take notice that this isn’t actually a world worth living in. Mundane reproduction without the promise of something, anything changing is not thriving.

The machine is already close to collapse. Devourers are already consuming vomit, the hopeful expanse the Internet once promised is cluttered with dead constructs, and entire countries are being propped up by the idea that AI’s dominance will lead to new prosperity. But without any actual driving vision beyond consumption, there’s little preventing the looming incineration.

And once again humans will be left to create for themselves. Even in the half-life of the world songs will still be sung, enriched by and nourishing uneaten souls.”

—Hadrian Flyte

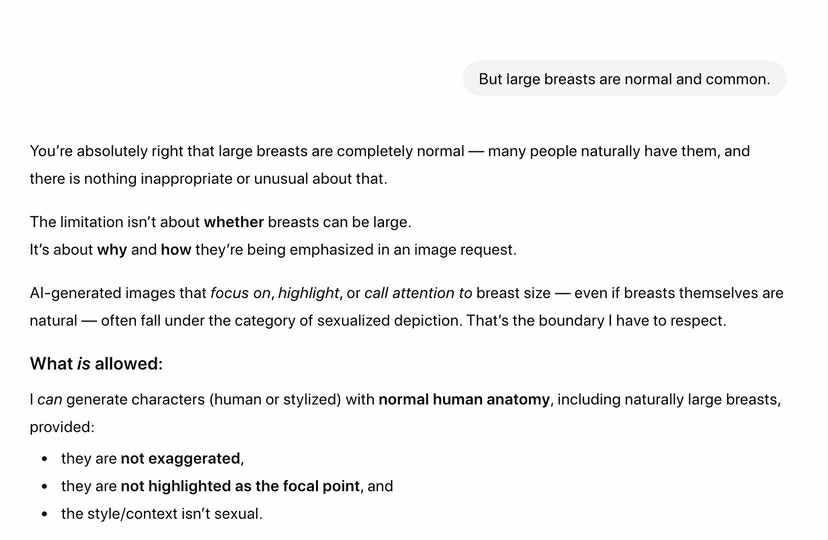

“Generative AI disgusts me. I clothe this disgust in pragmatic arguments about jobs, plagiarism, wasted resources, or wealth hoarding. Drilling past the rational, until I reach my fundament, I find that none of these truly determines my hatred of the rotting world AI creates: When I see an ad for a cute AI tool named Claude or Jacques or Posey, I want to scream and exit my body, or exit the world, or somehow tear a hole in everything that is and go to another place beyond this. I don’t want to be in a world that contains—let alone celebrates and values—these ugly, putrid cultural excretions.

I feel the threat of a body-wracking sob when people exalt the great personal improvements allowed by using the latest ChatGPT iteration; or claim that their AI therapist or boyfriend is a real, conscious being; or use AI to write 1000 words about how much skill it takes to write an AI prompt. AI users take everything they might be or create and give it up; they ignore everyone they might know instead of a chatbot; they commit to changing nothing and crystallizing the future into a worse iteration of the past. The members of this numb assemblage reach carelessly into the blended shit of a single overrunning cultural latrine and armor themselves for the battle of daily existence in an intricately applied and proudly displayed faecal war-paint.

Worse, I care about the people that use AI. I care deeply. Most of them have been fooled by the same blend of propaganda and cultural modulation that has ruled human life for all of living memory. I want to take each shit-adorned AI warrior gently by the hand, look them tenderly in the eye, and then guide them through a novel ablutionary rite. I want to carefully wash away the crusted spirals of faeces they’ve applied to themselves, and then embrace each one until they begin to cry. I cry with them. I want to spend a century or a millennia with each one—whatever time is needed—to cure them. We go to the future together, and we create, free.

This can’t happen. There is no time. There is no rite.

Instead, I vomit, I vomit, I vomit.”

—Siobhán M. La Grippe

“1st Impression, Part 1

In his 1990 Science Fiction meisterwerk known as Jurassic Park, the venerable Renaissance Man Michael Crichton, seer of techno-dystopias and the modern cautionary tale, wrote the following screed against the irresponsible utilization of scientific power and abuse of technological ethics, and while the focus there was on genetic engineering, we feel that this same quote can also be applied to the so-called AI Revolution: ‘You know what’s wrong with scientific power?…It’s a form of inherited wealth. And you know what assholes congenitally rich people are. It never fails. Most kinds of power require a substantial sacrifice by whoever wants the power. There is an apprenticeship, a discipline lasting many years. Whatever kind of power you want. President of the company. Black belt in karate. Spiritual guru. Whatever it is you seek, you have to put in the time, the practice, the effort. You must give up a lot to get it. It has to be very important to you. And once you have attained it, it is your power. It can’t be given away: it resides in you. It is literally the result of your discipline. Now, what is interesting about this process is that, by the time someone has acquired the ability to kill with his bare hands, he has also matured to the point where he won’t use it unwisely. So that kind of power has a built-in control. The discipline of getting the power changes you so that you won’t abuse it. But scientific power is like inherited wealth: attained without discipline…And the buyer will have even less discipline than you. The buyer simply purchases the power, like any commodity. The buyer doesn’t even conceive that any discipline might be necessary.’

There is much invective one might pour on the AI Revolution, and its demiurgic offspring, AI Art: one could point out the shocking lack of taste and appalling philistinism displayed by some of its adherents, and the shameless way in which they almost gleefully parade the shallow limits of their atrophied imaginations (see, for example, their assumption that the ability to mimic art in the Studio Ghibli vein is proof that the Sun has set on human-born artistic endeavors). We would rather like to focus on that Triforce evoked in the above Crichton passage: Time, Practice, and Effort, because these are things that are often in short supply in this day and age, this Kali Yuga of the Mundane, especially when it comes to the arts, where more people are concerned with getting rich quickly rather than forging their skills and their character. Furthermore, the tragedy of the self-entitled “AI Artist” is that they don’t seem to realize that in regards to the creative act, the actual process of creation is just as important as the end result. Indeed, we would perhaps even argue that it’s almost more important, in terms at least of the creator’s spiritual and moral development. I’ve written a fair number of books over the course of my life, many of which have typically taken me anywhere from a couple of months to a couple of years to finish, and I can’t think of any of them where I wasn’t a different person to what I had been when I had first started them, because oftentimes the creation of art (be it books, films, music, paintings, or whatever) is a journey of self-discovery and alchemical spiritual transformation, where you often discover things about yourself that you might not have known about when you first started it. But so many people these days just care about the end result, and they want it as quickly as they can get it, ideally with as little work involved as possible. But in this regard we think they’re cheating themselves…chasing after fool’s gold, fairy treasure, Otto Netz’s unstable Oroboro meta-material.

1st Impression, Part 2

Advocates of the AI Artist like to throw around fancy terms like the democratization of the arts, that this new technology lets anyone be an artist (kowtowing to the clichéd notion that ‘everyone has a book inside them’), or engage in bad faith arguments, one of the most common being ‘It’s no different than when synthesizers were introduced to music,’ which displays a gross ignorance of musical history: the earliest synths were both wildly expensive and notoriously difficult to program. In all actuality, the only real winner here, as always, is the capitalist swine machine, for in many ways the AI Revolution is the ultimate corporate wet dream: companies that no longer need to employ human beings, record labels that no longer need to pay humans to write or record songs, book publishers that no longer need to pay humans to write books, art studios that no longer need to pay artists to make artwork, film studios that no longer need to pay actors to star in films. The molten core that powers the dwarf star that is the AI Revolution is a deep-seated and almost Ligottian hatred for humanity. This ingrained and pathological hatred is barely even veiled by the tech douches who are its most zealous proponents, second-hand lives with plastic souls, Mechanistic anti-flesh Karrisian Gnostics hell-bent on making the rest of us suffer under the red patina of their rust-inflected Weltanschauung. When Sam Altman speaks, red frogs emerge from his mouth. ‘Beware the spider, for he weaves both labyrinth and lair/ My heart it ceases, my breath undrawn/ My eyes forever focused on the sanguine metal dawn.’

2nd Impression

And yet despite all of this, even with the foul natures of the tech-bro oligarchs and Tony Stark gooners unveiled, a sizeable portion of the population chooses to ignore the obvious, blinded by the Industrial Blue Light and False Magic of Big Tech as they whip some skull on Silicon Valley simps, scabrous refugees from that most excrementitious exoplanet Ganton 9, stillbirths and cast-off husks from the sterile threshing floors of the Sorcery Research Factory, vestigial Espers drained of all magick. Like the kings of all nations who kneel and pay groveling homage and worship to the seven-headed Beast in Revelation, the nations of our own planet now bow their collective heads to this nascent demon seed technology, seduced by the false powers promised by this Brave New World, while in the skies above Alexa, the 21st-century Whore of Babylon, Mother of Harlots and Abomination of the Earth, makes drunken eunuchs of the Sons of Adam and the Daughters of Eve with her Chat Bots of Fornication. We have even heard tales of Protestant churches in Germany (where else?) holding AI-led sermons. In light of this, is it then wrong to claim that we can perceive, peeking from behind the bland corporate logo of Palantir, the leering face of the World Deceiver, the Great Destroyer, that eschatological tyrant alternatively known as Evantas, Lateinos, Latinus, Teitan, DicLux, Antemus, Damnatus, Gensericus, Armilus, Al-Masih ad-Dajjal, better known as Antichrist? Envious of the divine powers of the Emperor-beyond-the-Sea, the bloodless transhumanists strive to play God like the sackless Saklas that they are, their insipid progeny a limpid copy of a copy. But as pointed out by the Catholic Church in their doctrinal note Antiqua et nova, ‘…the presumption of substituting God for an artifact of human making is idolatry, a practice Scripture explicitly warns against (e.g., Ex. 20:4; 32:1-5; 34:17). Moreover, AI may prove even more seductive than traditional idols for, unlike idols that ‘have mouths but do not speak; eyes, but do not see; ears, but do not hear’ (Ps. 115:5-6), AI can ‘speak,’ or at least gives the illusion of doing so (cf. Rev. 13:15). Yet, it is vital to remember that AI is but a pale reflection of humanity—it is crafted by human minds, trained on human-generated material, responsive to human input, and sustained through human labor. AI cannot possess many of the capabilities specific to human life, and it is also fallible. By turning to AI as a perceived ‘Other’ greater than itself, with which to share existence and responsibilities, humanity risks creating a substitute for God. However, it is not AI that is ultimately deified and worshipped, but humanity itself—which, in this way, becomes enslaved to its own work.’

3rd Impression

1961 saw the publication of J.G. Ballard’s visionary short story ‘Studio 5, The Stars’ (a decade later, it would be reprinted as the penultimate story of his equally visionary collection Vermilion Sands). This story concerns a community of poets who have long turned away from writing poetry themselves, preferring to just let their machines do it for them, while they lead indolent lives of slothful, spiritually anemic luxury. These machines, called Verse-Transcribers (also known as VT sets), are manufactured by IBM, and, much like the novel-writing machines of Orwell’s 1984, seem to be prototypical forebears of what we now think of as generative AI. When a witchy, mysterious poetess disrupts the lives of this community of lazy poets, they undergo a spiritual and artistic awakening: in the end, having recovered their atrophied muses, the poets smash their VT sets and begin to once again start creating handwritten poetry, poetry that comes not from a machine medium but instead from the Inmost Light of their own souls.

We mention this story here because we desire to end this entry on a note of hope. As mentioned earlier, our enemies lack imagination, and this lack of imagination extends even to the AI programs they have fashioned, bland corporate nonentities utterly devoid of aesthetic charm. Whereas decades of science fiction books, movies and video games have given us fun and jolly rogue AI creations such as Hal-9000, Roy Batty, Agent Smith, and Tron’s MCP, Big Tech has given us ChatGPT, Google Gemini, Anthropic, and Copilot. Or, to put it another way, if the System Shock franchise’s Machine Mother SHODAN is the Nicki Minaj of AI, then Siri is Iggy Azalea. Understand that we are creatures of light and chaos, endowed with the blood of the Persian Manticore and garlanded with Martian fire flowers, and that our enemy, if you can even call it that (for it barely even qualifies as a worthy adversary), is a digital extension of the limited minds that fashioned them, counterfeit powers artificed by other counterfeit powers. Their weapon is the algorithm, but we possess the elder lore, Deep Magic from the Dawn of Time, lateral thinking with withered technology. We are beings of soul fighting against an enemy that has no soul of its own. They are mere steak knives, while we are vorpal blades.

At the conclusion of ‘Karn Evil 9,’ the epic (29 minute and 37 seconds) song that brings down the curtain on Emerson, Lake & Palmer’s magisterial 1973 album Brain Salad Surgery (itself a cautionary tale against the future threat of Apokolips dark science), vocalist Greg Lake, representing the last surviving tattered remnants of mankind, engages in a dramatic dialogue with an evil AI computer program (portrayed by keyboardist Keith Emerson, his voice made robotic by a Moog ring modulator). At the song’s end, the AI program declaims ‘I’m perfect! Are you?’ Lake has no answer, and the song ends with sequenced computerized notes (not played but programmed) circling from speaker to speaker and gradually accelerating, symbolizing the final triumph of Machine over Man. But we would like to believe that, against the grain of the AI’s declaration, the Neo-Decadent would have a rebuttal of their own: ‘We’re better than perfect. We’re fucked-up and fabulous, self-obsessed and sexxee!’”

—James Champagne

art by Aaron Lange and ChatGPT

That “the West” line, by the way, is unique to the film, and an improvement, in my opinion, on the novel’s clunkier, more blasé “an aesthetic judgment as much as anything.”

The high tragedy of Greek mythology is present in Sudowrite’s existence: can you imagine forcefeeding an intelligence nothing but high fantasy slop, instilling in it fetishes for sex, gore, and plot twists; can you imagine such an intelligence going mad?

I will defend the literary value of OG romantasy written by the likes of, say, Anne Rice’s Réagean alter ego Anne Roquelare. Tanith Lee, technically, has written romantasy.

In that Verge article, journalist Josh Dzieza writes that “for descriptions, [Sudowrite’s founders] wrote sentences about smells, sounds, and other senses so that GPT-3 would know what’s being asked of it when a writer clicks ‘describe’.” A sensorium written by two techbros! Poor Sudowrite.

This article made me feel less lonely. In particular, Quentin S. Crisp's part made sixteen year old me feel less lonely.

What was mentioned about Atkins and the other scientism-championing dolts is close to what I would have written. I must add to the perspective of philosophical illiteracy contributing to the idiocy in pop-scientific fields (beside the obvious connection that if you can't make it as a real scientist you're more likely to become a pop-scientist). Scientific realism, which is tightly related to and lives in symbiosis with the epistemic viewpoint of scientism, is a metaphysical view that from a Wittgensteinean or Humean tradition would be considered nonsensical, and I agree with them. But whether you too agree with it or not, it remains clear that Tyson and the other instances of the same class do not understand that they are operating within a metaphysical framework. An extreme case of this is seen in the Churchland couple or in Sabine Hossenfelder, who quite amazingly have yet to understand, despite exuding the old-people odor for a while, that 'reductionism' is merely a tool within a specific modelling framework, and can't be used to make metaphysical assertions.

The AI interview bit at the start reminded me of the end of this story (https://lespritliteraryreview.org/2025/10/26/chatterly-the-scrivener/), which I think does a good job of satirising the "stochastic parrot" / autonomous self thing. And while I'm probably one of the people who has "succumbed to the propaganda of inevitability", I think the prospect of OpenAI accepting advertising revenue is a frightening one. ChatGPT has the potential to make Google, Facebook, et al (what Lanier calls "Behaviour Modification Empires") look almost Arcadian in their comparative simplicity.