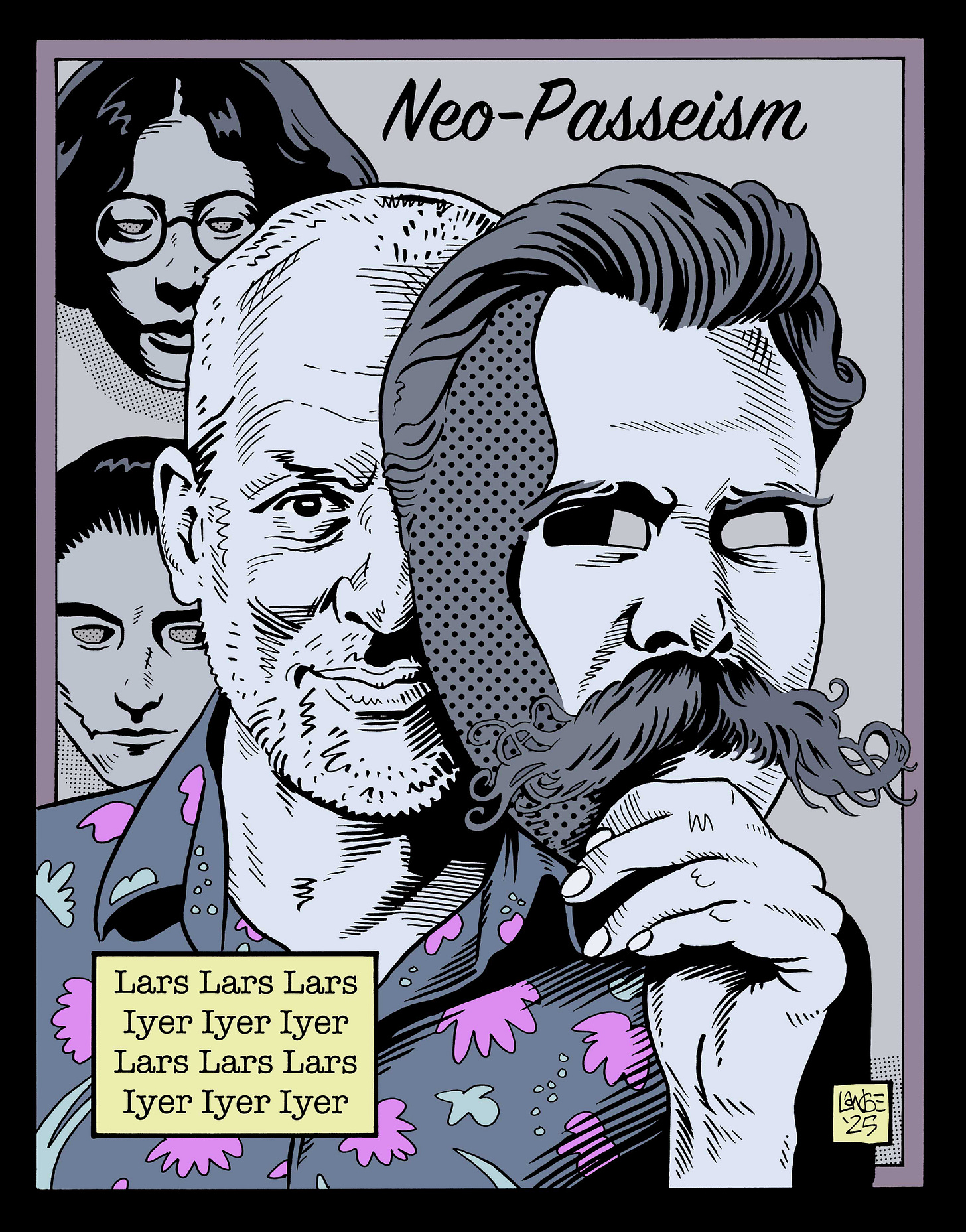

Lars Iyer

A Literary Manifesto After the End of Neo-Passéism

by Justin Isis

Lars Iyer is an elderly British academic who has commercially released several accretions of text marketed as novels. If you haven’t heard of Iyer, you are certainly in good company, and it may reasonably be wondered why he merits the consideration we are giving him here as an exemplar of Neo-Passéism. We will address what we consider meaningful objections to this sustained analysis:

Iyer is of no consequence, so focusing on him is an example of “stacking the deck” or some other dishonest rhetorical strategy. It is “punching down” to single him out, and it would be better to focus on broader, more visible targets of the Anglosphere such as Sally Rooney, the ever-execrable Zadie Smith, various unreadable young American “influencer-writers,” etc.

We reply that these targets, while responsible for no end of instantly-outdated period pieces, are also so broad that less can be learned from them than from a more apparently obscure figure. We add that Iyer is in fact characteristic of his generational cohort, and representative of more widespread tendencies beneath the surface of the current Anglosphere “literary culture” (the cradle of Neo-Passéism). That he has not attracted further critical attention is simply due to no one having much to gain by highlighting him. And, given that this article is not monetized, we admit that we could have spent the time writing it on more worthwhile activities such as promoting club events or smoking crack in a McDonald’s restroom. As such, we will try to confine our analysis to several remarks on one of his most telling public utterances.

Iyer’s works are intended to be light comedy, and subjecting them to serious scrutiny is a bit like deep frying a soufflé.

We retort that this would be the case were Iyer’s novels at all funny—but rather than achieving comedy, they merely announce their comedic intent. Their cumulative effect is quite wearying, given the lack of convincing characters and overreliance on references to dead writers and philosophers. Comedy can make use of caricatures and broad cliches, but this works best when contrasted with some depth. The alternative is farce, but Iyer lacks the true madcap instinct to achieve that either. It is impossible to imagine him lasting more than a few seconds in a comedy club, given his uncharismatic mien and reliance on stock material. Readers of novels are apparently taken to be a more forgiving audience, but really, why should they be? Pushing through an excruciating novel is more work than simply enduring an inept comedian at dinner.

Iyer’s works are highly scene-specific; if you haven’t experienced the sort of British academic milieu they ostensibly satirize, then their import will remain obscure.

This is the least convincing objection, given that Iyer fails to move beyond caricature or otherwise make his chosen scene broadly interesting. It could be argued that Iyer’s portrayal is in fact “believable” or otherwise accurate, but this is doubly damning. If the world of morose British academics is in fact even LESS interesting than we assumed it to be, then it would take true literary skill to make it worth reading about.1 It’s possible to think of writers who pulled off something like this with similarly unpromising material (Kingsley Amis comes to mind), but Iyer’s literary and comedic skills are nowhere near the requisite level.

In short, we consider Iyer to have failed at the task he himself has chosen.

Iyer’s novels consist of a trilogy and three separate, more recent works. The pseudo-autofictional (to the extent that it contains a protagonist named Lars) trilogy beginning with Spurious (2011) is perhaps the most tedious, though not necessarily the worst-written: it is, however, very poorly-written. Over the course of the three volumes, two sub-Beckettian academics waste time talking to each other about nothing. This is all that needs to be said about Iyer’s first three works, which in their intentionally plotless and unintentionally patronizing way are much more impressed with themselves than an unbiased reader is likely to be.

Wittgenstein Jr followed in 2014. It concerns a Cambridge academic who is reminiscent of Wittgenstein, etc. etc. Tibor Fischer, who once referred to a Martin Amis novel as “not-knowing-where-to-look bad… It's like your favourite uncle being caught in a school playground, masturbating," described Iyer’s Wittgenstein-rip in The Guardian thus: “For a philosophical novel, the book could be a bit better thought out; it is more of a witty short story or novella that has been bullied into the territory of a novel.” We feel that Mr. Fischer’s apparently characteristic wit has deserted him here, and that he really should have brought out his masturbating playground uncle simile once more, to describe a worse book: that book being, of course, Wittgenstein Jr.

In the unfortunately-titled Nietzsche and the Burbs (2019), which brings to mind the marginally better-written The Buddha of Suburbia by Hanif Kureishi (1990), Iyer again foregrounds his strategy of feigning significance by parasitically indebting himself to better writers and philosophers, inserting characters who have renamed themselves (or been renamed) after the figures in question. This “name-grabbing” scam didn’t work when Haruki Murakami, Japan’s most Boomer writer, tried it with Kafka on the Shore (2002), and Iyer isn’t doing any better.2 The fanfictional approach that results simply highlights the immense gap that yawns between Iyer and the figures whose aura of significance he tries but fails to steal.

Iyer’s prose reaches its nadir in his most recent work, My Weil (2023). As the title indicates, this time it’s Simone Weil’s turn to be siphoned for second-hand significance; presumably the recent spate of Huysmans Flips and other retrograde spiritual contortions has moved her to the front of the queue. All the flaws of the previous works are magnified here, with Iyer seemingly having given up on even trying to write at an adult level. The novel as published feels like a rough draft, sloppily sketched out in a lazy, Young Adult-style narrative shorthand of fragments and dangling, disconnected gerunds. Subclauses have been abandoned. It is written in the present tense, because Iyer is nothing if not an academic, and this is the default “workshop” style of the past thirty or forty years.

Several possibilities for why Iyer has chosen this form of narration present themselves:

1. A misguided attempt at creating a comedic contrast between the “breeziness” of the prose and the “weighty” philosophical themes supposedly being invoked.

2. Sheer commercial calculation: current standards are low, so why aim higher? Counterfeit “immediacy” for perceived broad appeal.

3. Genuine incompetence/inability to write to a publishable standard.

4. All of the above.

Iyer’s characters here are weightless names on the page, devoid of description and depth. Many are given sobriquets to clue us in to their central casting: we get the “den mother,” the “Business Studies Guy,” etc. The book’s “intellectual” pose is a thin veneer that translates poorly to novelistic prose, and the cultural capital that Iyer strains for with his endless name dropping is on the level of a Hot Topic or UNIQLO T-shirt. Simply mentioning Nietzsche, Wittgenstein, Weil, etc. is not enough to invoke their ideas, much less seriously engage with them.

The slippery retort here would be that Iyer is satirizing just such intellectual glibness, and that his characters are Neo-Passéists on purpose. But this is entirely too charitable.

We will confine ourselves now to a short(ish) text published more than ten years ago in the (apparently unintentionally?) hilariously-named The White Review.3 Here we feel that we are being generous to Iyer, since the piece is at least grammatically inoffensive and moderately coherent, in contrast with his recent attempts at fiction.4 The content, though, is inane. It purports to be a manifesto, and as we have personally spent some time restoring the art manifesto to its rightful place in the 21st century’s rhetorical arsenal, it pains us to see Iyer failing to do the same. The pompous, mock-valedictory title is “A Literary Manifesto After The End of Literature and Manifestos.” Iyer has stated that he wrote it “in a spirit of provocation.” We are therefore taking up the challenge and addressing the piece’s internal logic, which contains numerous errors.

Once upon a time, writers were like gods, and lived in the mountains. They were either destitute hermits or aristocratic lunatics, and they wrote only to communicate with the already dead or the unborn, or for no one at all. They had never heard of the marketplace, they were arcane and antisocial. Though they might have lamented their lives—which were marked by solitude and sadness—they lived and breathed in the sacred realm of Literature. They wrote Drama and Poetry and Philosophy and Tragedy, and each form was more devastating than the last. Their books, when they wrote them, reached their audience posthumously and by the most tortuous of routes. Their thoughts and stories were terrible to look upon, like the bones of animals that had ceased to exist.

Later, there came another wave of writers, who lived in the forests below the mountains, and while they still dreamt of the heights, they needed to live closer to the towns at the edge of the forest, into which they ventured every now and again to do a turn in the public square. They gathered crowds and excited minds and caused scandals and partook in politics and engaged in duels and instigated revolutions. At times, they left for prolonged trips back to the mountains, and when they returned, the people trembled at their new pronouncements. The writers had become heroes, gilded, bold and pompous. And some of the loiterers around the public square started to think: I quite like that! I have half a notion to try that myself.

Soon, writers began to take flats in the town, and took jobs—indeed, whole cities were settled and occupied by writers. They pontificated on every subject under the sun, granted interviews, and published in the local press, St. Mountain Books. Some even made a living from their sales, and, when those sales dwindled, they taught about writing at Olympia City College, and when the college stopped hiring in the humanities, they wrote memoirs about ‘mountain living’. They became savvy in publicity, because it became evident that the publishing industry was an arm of the publicity industry, and the smart ones worked first in advertising, which was a good place to hone the craft. And the writers began to outnumber their public, and, it became apparent, the public was only a hallucination after all, just as the importance of writing was mostly a hallucination.

Once upon a time, liberal humanist academics (mournful secular Christians with concealed metaphysics) convinced themselves that they were “writers” rather than merely glorified school teachers. They made pronouncements to those of their class group but did not notice that no one else was listening. They elicited polite publicity from the usual legacy organs. But no matter how many reviews and awards nominations they collected, these trophies did nothing to alleviate their underlying sense of irrelevance.

These literary Neo-Passéists did not see that they themselves were the cause of the situation they lamented. They wrote books with titles referencing Nietzsche, Wittgenstein and others, hoping that the halo of significance stolen from their betters would transfer some deeper meaning to their material. This did not, to put it bluntly, happen. The idea of simply relying on their own imaginative resources did not occur to them.

Their “manifestos,” rather than rightly being lists of demands and pronouncements of vital activity to come, were instead tepid diagnoses of their own impotence. The only thing that “manifested” was the general indifference of the public, and of younger writers who were unwilling to consign themselves to a subordinate cultural position.

We feel that this is a more honest rephrasing of the first three paragraphs.

Now you sit at your desk, dreaming of Literature, skimming the Wikipedia page about the ‘Novel’ as you snack on salty treats and watch cat and dog videos on your phone. You post to your blog, and you tweet the most profound things you can think to tweet, you labour over a comment about a trending topic, trying to make it meaningful. You whisper the names like a devotional, Kafka, Lautréamont, Bataille, Duras, hoping to conjure the ghost of something you scarcely understand, something preposterous and obsolete that nevertheless preoccupies your every living day.

Iyer seems constitutionally incapable of writing a manifesto on how to buy groceries from Tesco, much less on how to address the future of literary art. He has only 20th century post-existentialist “exhaustion” and “absurdity” to fall back on, which now seem about as relevant as a moral lecture by F.R. Leavis, or Carlyle digressing Victorianly on the meaning of life. Iyer can’t see that we’re no longer in the Kafka-Wittgenstein-Weil century (or Lautréamont, Bataille, Duras century), and that different polarities now apply. There IS a new Current in writing, but academics will never tune in to it, much less transmit it.

The oft quoted fact: there are more graduates of writing programmes than there were people alive in Shakespeare’s London.

Iyer, like many in the guild, seems to assume that there is some inextricable connection between academia and what is still gratingly termed “creative writing” (the correct term is simply writing).5 He therefore limits his purview to graduate students and professors—and even high school students, in his novel which appropriates the name of Friedrich Nietzsche (a reliably amusing adult who referred to himself as Dionysus and expired in somewhat less than ideal circumstances). The British educational institution fetish is given free reign. We are reminded at last of a certain well-known fantasy series—and it may be argued that Rowling’s literal children’s books, though trite drivel, actually contain more sophisticated narration than Iyer’s fictionalized “philosophical investigations,” to use a term taken from Wittgenstein (an abusive elementary school teacher who was born into great hereditary wealth). If you felt reflexively and justifiably annoyed at the potted explanations of Nietzsche and Wittgenstein just given, try to imagine this tic taken to the extreme—in fact executed even more crudely—and you have something of the texture of Iyer’s work. It gives us no pleasure to have to invoke dead thinkers when not warranted, but Iyer considers it a necessity, given that his work obviously cannot stand on its own.

And yet… in another sense, by a different standard, Literature is a corpse and cold at that. Intuitively we know this to be the case, we sense, suspect, fear, and acknowledge it. The dream has faded, our faith and awe have fled, our belief in Literature has collapsed.

We do not think that Literature was ever intended to be an analogue for some form of “belief,” “faith,” or “awe”-based monotheism: and if it was, then we celebrate its death and will get on with our resolutely antinomian, occult takes on language art. Iyer and other academics are free to weep themselves blind at the ersatz tomb of “Literature,” but we do not wish to be notified further of their cloying emissions.

We also do not think that Iyer should presume to tell other writers and artists what they “intuitively know.” For us, Literature is only beginning.

Literature has become a pantomime of itself, and cultural significance has undergone a hyperinflation, its infinitesimal units bought and sold like penny stocks.

Does the fault lie with Literature, or does it lie with Iyer? We suspect that the academic is protesting and projecting too much. We find the work of young men and women to be greatly diverting, unlike fiction preoccupied by the stodgy “weight” of Kafka and a whole cemetery’s worth of other estimable corpses. It is only when our attention is drawn back to the dreary world of the university, the Big 5 Publishing Scene, the need for “cultural relevance,” or the even more revolting “reality hunger” that boredom sets in.

Writers now work in concert with capitalism, rather than setting themselves against it. You’re nothing unless you sell, unless your name is known, unless scores of admirers turn up at your book signings.

Not everyone is a sell-out or collaborator, and Neo-Passéism is always a choice. Iyer, as an employee of the modern academic guild, has made his choice to participate in the system. On his personal site, a sidebar lists a truly exhausting collection of reviews, broken down by year for more than a decade; publicity and attention are clearly important to him. It would appear that he believes he is nothing unless he sells, unless his name is known, and unless scores of admirers turn up at his book signings.

More seriously: the concept of a “book signing” is a joke. Much like “readings” (story time at the library for adults), no one under thirty cares about these tired rituals. If the aristocratic poet-gods that Iyer imagines in the first paragraph returned, does he think they would be at all impressed by his obvious attachment to superficial market conditions?

We have not run out of things to be serious about—our atmosphere boils, our reservoirs of water go dry, our political dynamic dares our ingenuity to permit catastrophe—but the literary means to register tragedy have exhausted themselves.

We find that the literary means to register the tragedy of credulous, nostalgic, lazily lugubrious Neo-Passéists are still very much in stock, and freely available to all who wish to use them.

If the history of Literature is a history of new ideas about what Literature can be, then we have reached a place where modernism and postmodernism have drunk the well dry. Postmodernism, which was surely just modernism by a more desperate name, brought us to our endgame: everything is available and nothing is surprising.

We are back in the worst of the 1990s. Twenty-five years later, this moribund, end-of-history “postmodernism” is deeply dated. To anyone not comfortably ensconced in the academic milieu, the name dropping and de rigueur “exhaustion” seem like default stances rather than novel, compelling or surprising critiques. Postmodernism is Neo-Passéism, the last security blanket of the artistically senile.

In the past, each great sentence contained a manifesto and every literary life proposed an unorthodoxy, but now all is Xerox, footnote, playacting. Even originality itself no longer has the ability to surprise us. We have witnessed so many stylistic and formal gambits that even something original in all its constituent parts contains the meta-quality of newness, and so, paradoxically, is instantly recognisable.

“Originality is no longer possible” has long been the lament of those incapable of originality. For everyone else, it is simply a pleasing practice performed for its own sake. Anxiety and self-consciousness are evidence of incapacity.

Shame and scorn are the only response now at literary readings to literary manifestos.

We are truly saddened to learn that Iyer received such a response, but based on the quality of the manifesto we are now discussing, we can not claim to be surprised.

Whereas Kafka was born too late for religion, we are all born too late for Literature.

Religion is as common as weeds, and we are nothing if not in the thick of it. Literature is perhaps a more rarefied growth, but not by much. We look to the future and see much more religion, and much more Literature.

Note clearly that we did not state that the religions of the future would bear much resemblance to anything that Iyer (or Kafka) would understand by the term. Nor will the Literature of the future.

It’s time for literature to acknowledge its own demise rather than playing puppet with the corpse. We must talk directly about the farce of a culture that dreams of things it cannot possibly create, because this farce is our tragedy.

The attempt to lower the bar, as it were, crippling imaginative potential in line with one’s own limited faculties, is worthy of disdain. The strategy employed is a barely-concealed wish that the reader should become as artistically effete and shriveled as Iyer: a bit like having bowel cancer and wishing it were transmissible: “I wish everyone felt as tired and pained as I do.” But we who are not yet in the aesthetic nursing home do not feel the need to suffer along with him.

Use an unliterary plainness. It knows the game is up, that it’s all finished.

We could, but that would be boring. The violent exercise of poetic faculties—something which Iyer has clearly never felt in his marrow—demands the full range of convulsive verbal freedom. Why restrict ourselves to the cramped enclosure of Iyerprose?6

Mark your gloom. Mark the fact that the end is nigh. The party’s over. The stars are going out, and the black sky is indifferent to you and your stupidities.

The atmospheric conditions of the British Isles are notoriously gloomy, in the artistic and certainly the meteorologic sense, and we suspect here that the latter may be influencing the former. This can be amusing in small doses, but soon surfeits the imaginative reader of sanguine temperament. The world ended a long time ago, and the party is not, in fact, over; Iyer simply wasn’t invited.

There is much more that could be said here, but it would be truly exhausting to refute every single line, so we will allow Iyer’s performative pessimism to speak for itself.7 It is a measure of how far standards have fallen that this “don’t innovate, don’t try to be interesting, don’t imagine anything new” stance has until now gone unchallenged, and it would be difficult to think of any other field of endeavor, artistic or otherwise, where it would be given a pass or even praised. We could rightly single out the literary culture of the aforementioned Angloid archipelago for encouraging Iyer’s LCD embrace of the status quo, although, as stated at the beginning, a similar don’t-rock-the-boat perspective prevails in the broader world of publishing. But however tempting laziness and resignation might seem, in the end they will contribute nothing lasting or relevant to the Literature of this century.

Finally, at the risk of being accused of wokeness, we must remark that Iyer confines his definition of Literature to a fairly narrow Eurocentric spectrum: the contemporary writers of South America, Africa and China would seem to be of no importance. The possibility of a truly crosscultural, syncretic avant-garde remains beyond his conception, given that he seems unable to imagine a Literature that transcends Kafka, Bernhard, etc. We note too that the manifesto acknowledges only the achievements of male writers; presumably Iyer considers the class of female beings known as women to be incapable of producing and participating in the vast validating Meaningspace™ known as Literature. These are boring observations to have to make, but then Iyer’s manifesto is very boring.

In conclusion:

Iyer’s professor-as-Nietzschean-Last-Man pose belies his lack of core imaginative strength and, ultimately, lack of personal responsibility in generating a new artistic Current. There is no chance of any young person being inspired to action by his manifesto, which is saturated in the kind of gurning pessimism characteristic of those who grade papers for a living instead of inhabiting the vital artistic spaces of the present. Iyer mistakes his own anomic irrelevance for that of Literature’s, with results that are ultimately less comic than terminally wack.

All young writers and artists are advised not to waste their time with the exhausted exudates of the academic guild complex, redolent as they are of the 20th century and its outmoded “postmodern” museum culture.

art by Aaron Lange

And we assumed it to be REALLY uninteresting. The heroic practical struggle of the average plumber to unclog a stubborn drain would present a more sustained and “relatable” engagement with contemporary reality than any novel-length description of British PHD students wasting time and public resources.

Name-grabbing has become such a Neo-Passéist grift that it deserves an entry of its own. Think Hemingway’s Chair (1995), Reading Lolita in Tehran (2003 ), Balzac and the Little Chinese Seamstress (2000), Lovecraft Country (2016), and countless others (the appropriation of Jane Austen in particular has gone on long enough at this point to shade into abuse—something we can’t help but condemn, even if we are inclined to agree with Mark Twain’s assessment of her works). Iyer isn’t even the first to name-grab Wittgenstein either, as David Markson’s vastly superior Wittgenstein’s Mistress (1988) proves. It’s hard to imagine that Ludwig would have been pleased by these “tributes” (and Kafka would likely have been disgusted/horrified beyond measure). As it stands, name-grabbing is practiced only by the terminally middlebrow.

Home of the whitest kids you know!

The novels really were much worse to actually sit down and read through in full than we have managed to suggest here. Pushed to the point of coming up with ANY constructive criticism, we suggest that Iyer’s temperament and imagination would be better suited to some form of experimental drama or theater production, given that he seems uninterested in (or incapable of) written narrative pacing, description, dialogue, lyricism, character depth, or any of the other appurtenances of fiction.

In the course of researching this article, we subjected ourselves to a video containing over four actual hours of Iyer conducting, via teleconference, something referred to as a Creative Writing Workshop. The ensuing tedium calls to mind the Meshuggah song concerning “the exquisite machinery of torture.” Iyer sees fit to impart no meaningful examples of great writing, no rhetorical strategies, nothing but a series of vague prompts, most of which are circular or self-defeating (he begins with a quote from Gabriel Josipovici, another backwards-looking British academic who is nostalgic for Modernism of the Bloomsbury kind). The students, who have presumably paid money for this, seem hapless and genuinely bewildered.

Bolaño, Bernhard and the other writers Iyer discusses are of course worth reading. But we do not think that any possible “lateness” or other elements of exhaustion present in their work should be taken as templates for any writer under, say, sixty. It is also no longer the 20th century, and no young creators now working have ever personally experienced the kind of “high art” monocultural conditions that inspired such conflicted feelings in Bernhard. “Nostalgia for something you never experienced” is a known phenomenon, but in this case, it is likely to produce unintentional kitsch.

We didn’t even get into Iyer’s numerous interviews, in which he embodies the now-standard Neo-Passéist stance of preferring music and film to writing. Reading his books is therefore a bit like sitting down to a meal from a chef who dislikes cooking and would rather be an architect. No interesting books will result from failed musicians and failed filmmakers; we want instead writers displaying the sort of natural-athlete obsession with and immersion in writing for its own sake, alongside a recognition that the writers of the past are peers rather than unapproachable pedestalled idols.

In other interviews Iyer apparently conflates Gnosticism and Christianity, quotes Saul of Tarsus approvingly, etc. There is really enough material for a potential Parts II and III of this article addressing the broader, deleterious metaphysical tendencies which inform his writing, but there are only so many hours in the day.