Rick Rubin

Rick Rubin is a Fraud—A Dime by the Dozen: Neo-Decadent Manifesto of the Record Producer

by

“I have no technical ability [as a recording engineer] and I know nothing about music.”

— Rick Rubin

The first the world heard of Frederick Jay “Rick” Rubin was in a failed local Long Beach joke band prophetically called PRICK. They played one show, at CGBG, where they were shut down after two songs, when they began arguing with hecklers. The audience was a mix of randos and plants that the band had brought along to intentionally start the conflict that ended the show. They did this to create media hype in faux-savvy style, devoid of substance. Mark the beginning of a theme that will serve Rick to the time of this writing.

The next the world heard of Rick Rubin was another non-starter of a self-described “art-core” band called HOSE. Unable to drop a ripple with any original material, they created a small buzz with reworked noise-punk versions of HOT CHOCOLATE’s “You Sexy Thing” and RICK JAMES’s “Superfreak,” in a cynical attempt at art1 that can only be described as clever. The Neo-Decadent individual should never be clever; be anything but clever. Clever is a hack attempt at life and should always be ridiculed by creative individuals. Clever makes you a PRICK.

The founding of DEF JAM RECORDINGS was a capitalization of these clever ideas that Rick Rubin cultivated with his father and High School A/V teacher, combined with a new angle that would also serve Rick well for the rest of his career to the present: cultural appropriation. Having been unable to understand Punk production in his own projects, Rick leeched all the knowledge of Hip-Hop culture that he could, and more importantly music production, from a brief and exploitative friendship with the legendary DJ JAZZY JAY of AFRIKA BAMBAATAA. Before Jay was ghosted, he introduced Rick to RUSSELL SIMMONS, an industry professional who could help Rick bridge the gap between his heretical bullshit and the consumer.

These lazy elements came together around 1985 to create the 3rd Generation Record Producer2, an unholy confluence of failure, hubris, overweening pride, misunderstanding, and capitalism. This wholly unnecessary position was unleashed on the world when Rubin briefly joined the BEASTIE BOYS as DJ DOUBLE R. The Beasties were convinced by Rick to run shows where they would play a punk set, then Rick would DJ, then the band members would do rap sets with Rick DJing. This eventually led to Rick convincing the band to run off their founding drummer KATE SHELLENBACH (later the drummer of legendary femme rock bands LUSCIOUS JACKSON and LUNACHICKS) and no longer be a punk band. Instead, they were to be amongst the first non-Black people to appropriate Hip-Hop culture in a half-assed and ambivalent way that still allowed them to release obviously Pop records like “(You Gotta) Fight for Your Right (to Party!)”. Kate did not fit into their—as ADAM HOROWITZ described—“new, tough rapper guy image” that Rick invented for them. Kate would later remark that Rick was a “sexist meathead” and describe how he turned the situation in his own favor, as he was getting his new record label off the ground. This was done while Simmons facilitated the signing of PUBLIC ENEMY, the handling of RUN-DMC and the release of LL COOL J’s debut single on Def Jam, projects to which Rick contributed beats.

A deeper ambivalence developed for Rick when he signed metal band SLAYER to the new Def Jam, and produced Reign in Blood, a record that sounds exactly like the master technician members of Slayer did in the rehearsal room and on stage at the time, save some aggressive 1980s reverb on the snare and some hack metal thunderstorm effects likely suggested by Rick. Simmons was not impressed.

The undoubted largest success of Rick’s career was borne of his new job title, his Production of the RUN-DMC remix of “Walk This Way” with shameless and indiscriminate sluts AEROSMITH3. This apartheid of a track, shat of the blithering 1980s music industry, dug a holocaust trench-grave that insults the intelligence of all involved, the consumer, and any God that man can create. This moment would later be often referenced as the high watermark of Rick’s career, and proof of his genius. Make of that single whatever you will. Consider, though, that later that year, when Rick tried to produce Aerosmith in earnest, doing what they were good at, he was quickly and quietly fired from the project. RUN-DMC certainly never came calling again. I believe this was the beginning of the end of his relationship with Russell Simmons. That breakdown, no matter what caused it, would necessitate the founding of DEF AMERICAN, later AMERICAN RECORDINGS, Rick’s lone venture to-that-date without anyone black.

As proof of Rick’s total lack of taste and inability to spin gold out of anything that was not already golden, he moved to California—after the breakdown with Simmons—and later produced some of the worst records of all time, the six RED HOT CHILI PEPPERS records beginning with 1991’s Blood Sugar Sex Magik through to those California records. ANTHONY KIEDIS is a predator and is the worst singer of all time, but Rick was ready to go, producer and life coach. The Hollywood Guru at last. If you’re going to give RHCP any credit at all, it all goes to JOHN FRUSCIANTE, who seems not to mind at all when Kiedis wang-dang-doodles all over some beautiful and intricate guitar composition. All the while, the man that many have described as the greatest Record Producer of all time didn’t have the wherewithal to make those records anything but undeniable trash, even with the continual presence of technician/engineers who assured that the tracking signal and mix were pro. If the performances had been right, it would have been down to the band.

All of this happened for Rick because he was good at one thing, writing beats. Russell Simmons—who abandoned his own RUSH RECORDS to become the real driving force behind Def Jam’s business—only ever gave Rick the time of day because of his ability as a producer by the Hip-Hop definition4, and his relationship with the Beastie Boys. If Rick were really “the greatest record producer ever,” as Simmons would seethe through clenched teeth in 2018, then he would have done his job and recognized the elements that worked. His work making records with LL and RUN-DMC was enough to impress Simmons, so that should have been everyone’s focus, had there been a real Producer around. The Simmons brothers wanted the beat that got used for “Walk This Way” for an original and instead were Produced into making a pop record that destroyed their relationships and a successful record label. Real nice Production skills, Rick.

“The goal is to progress and get better at your craft. Fortunately, this is something anyone can do.”

— Rick Rubin

I have always preached to any client, or anyone who would listen, in an expensive session or a trap house, in county jail or an academic online forum, that the key to an interesting bit of music or recording or art (or life?) is dynamic flow. You must use dynamics to weave your own thread into the cloth of creation. You must use them to dominate the observer in your hand, and strip them of their want or willingness to resist going exactly where you want to take them—then take them literally anywhere, as long as there is an element of dynamic flow. This dynamic flow is not limited to classical loud/soft or fast/slow contrasts, though ask PIXIES about those. It can be present in a piece of music that is nothing but loud from the first second, if the other elements (narrative flow, chord structure, melody, etc.) lend themselves well to this idea. HUM, MY BLOODY VALENTINE, RAMONES, and ELLIOTT SMITH are all good examples of dynamic musical flow without loud/soft dynamics. Creators in fields other than sound achieve dynamic flow in-line with their main stat: writers through narrative tension and release, and meter; visual artists through the use of chiaroscuro, etc.

Of the methods of dynamics available to the musician, however, by far the most common and most easily accessible is the loud/soft dynamic. It is certainly a tool in the belt of every mixing engineer that has ever lived. Arguably, no one has been a greater enemy of this form of dynamic flow than Rick Rubin. I’ll keep this part short—since better writers have discussed this unbelievable phenomenon more thoroughly over the years—but at the turn of the century there dawned THE LOUDNESS WARS, where Producers colluded with A&R and label bosses to deliver more highly compressed mixes (a compressor’s sole function is to limit dynamic range; it makes the soft parts louder and the loud parts softer, in layman’s terms) that could be slammed against the loudness wall in mastering, like an unloved coquette by a careless prom date. This was done for one cynical corporate reason; the louder a song was played, the better it tested with the plebs at the mall buying denim. Louder mixes meant that one song might appear louder when masters are played back-to-back like on radio. This ignorant thinking of course ignores the fact that we always have a volume knob right there, but whatever, it happened, it’s over. Rick was front and center.

There are exactly three elements that make for a well-made and artistically relevant record: number 1 is dynamic flow, number 2 is a band or artist that has a unique vision, and number 3 is a producing technician/engineer that helps the artist translate that vision to a tangible medium, ensuring the quality of a recording. The Rubinesque Executive Producer has no place in that equation, as he has no ability to function as a musician, recording engineer or agent of dynamic flow. His fear of these facts kept Rick physically away from later sessions that he was well paid for.

“The goal is to ignite you then move on”

— James Mercer

This writer had a client whose band’s tepid debut record was produced by Rick, and released on his American Records label, alongside a legendary producing technician/engineer. That engineer went on to full-on produce that band’s hall-of-fame sophomore record, often cited as one of the 100 best Rock records, with four number 1 hits. The debut record had one hit; it was a white-bread cover of a legendary Black song, another cultural appropriation5, perfectly on-trend for Rick. The only difference in the equation of these debut and sophomore records was the presence of Rick, and a couple of key line-up changes, adding of keys etc.; all these things are within the lane of a Producer to do, but Rick did not influence these decisions. He quietly faded into the shadows as the band released records on his American Recordings for years afterward and forged their own success.

To hear the lore surrounding this debut record, Rick commandeered one of the isolation booths in the studio where the band was working, moved in a treadmill and a speakerphone like what you would find in a call center, and ran while listening to a split of the console mains through the speakerphone. He would occasionally cue in to the control room to make asinine remarks as to the performance or direction of the recordings, while running on his treadmill. The band spent the rest of their lengthy career ridiculing this spectacle. I witnessed friends of that band troll them to remarkable success by playing the opening riff to that insipid cover—that Rick made them do—at opportune moments on stage or in the studio. 2/5ths of that band continues to reunite and tour when they need money, and they never play the Rubin-suggested debut single.

Around this time, another major label success act famously described Rick’s production style as “absent,” though later he retracted his statements, likely when threatened with never working again. Tony Iommi, similarly, but at the very end of his career and with nothing to lose, was quoted as saying, “I’m not sure what [Rick Rubin] does,” after Rick produced sessions for Black Sabbath. Iommi never retracted his statement.

Rick’s worst artistic behavior, though, was the dangling of the moldering corpse of JOHNNY CASH in front of a microphone—in Rick’s living room, where he recorded Johnny—while convincing him that the record would be good for his family and legacy. Then, during one session, he jump-scared half-dead Johnny with the sudden presence of GLENN DANZIG, crooner of THE MISFITS, who wanted to pitch a song. Can you imagine Lil’ Danzig doing his lil’ voice pitching his little song? MORRISSEY levels of embarrassing lack of self-awareness. Poor Johnny. What was he going to say? What did he even care? He knew he would die soon. The pain in his voice when he covered NINE INCH NAILS’s “Hurt” was real and genuine (very Neo-Passéist ingredients to spice a creative endeavor, anyway)—not because of the needle that dug a hole in TRENT REZNOR’s arm, but because Johnny Cash was a dying man in pain being manipulated by monsters.

“The work reveals itself as you go. It tells you what it wants to be.”

— Rick Rubin

Rick’s fanboys will argue that he cultivated a hands-off style that is reflected in the STEVE ALBINI ethos—one which allows the artist to be themselves—but this is not true. The crucial differences between Rubin and Albini are that Steve’s personal musical career was characterized by repeated success, not failures. Albini wrought his career with innovation and participation in an artistic movement, not stumbling colonization of others’ culture and ideas, with an invasive stamp of the Producer. Albini was a world-class technician/engineer, whereas Rubin does not know 1176 from 33609.

Steve was not perfect in these regards either, despite being well known as a hands-off producing engineer. The hands-off approach was hard-learned for him. Steve recorded, over-produced, and mixed Tweez, the debut of Louisville cult gods SLINT, being so deep in the project that he even did the design and layout for the album cover. There were production elements that Steve added to the recording, however. The band disliked these elements so much that the bass player quit the band when Steve delivered the mix. Two years later, when Slint went on to make their sophomore record, the legendary 10/10 Spiderland, they sought out a no-name studio with just a technician/engineer who agreed to record the band exactly as they sounded playing in a room. Albini was a smart guy; he saw this and owned his mistake, and never made that mistake again. His method became that of a photographer who documented a band as it existed, in a room.

Albini was also competent enough to give the artists production elements that they wanted, however. Reverb on the vocals? Sure. Make it sound more purple? He did his best to understand what the artist meant by purple and make it happen, thoughtfully. The lower-case “p” producer or technician/engineer is there to facilitate the artist’s art, not their own agenda and worldview. Steve Albini did all these things well and as a result later made his own 10/10 records like Pixies’ Surfer Rosa or PJ HARVEY’s Rid of Me, which displays the widest dynamic range of any record of which I am aware. Albini is intentional and present. Conversely, Rick Rubin’s occasionality and meandering needling puts him deep in Dunning-Kruger, with shovels for anyone willing to help dig, and he has never done anything but damage to any project and artist that he has been involved with after RUN-DMC and LL Cool J. His ideas of a band covering a song, or slapping formerly famous musicians together for a project, or debasing the legacy of a legend do not make him a Record Producer in any way that is not pejorative, they make him an A&R man6.

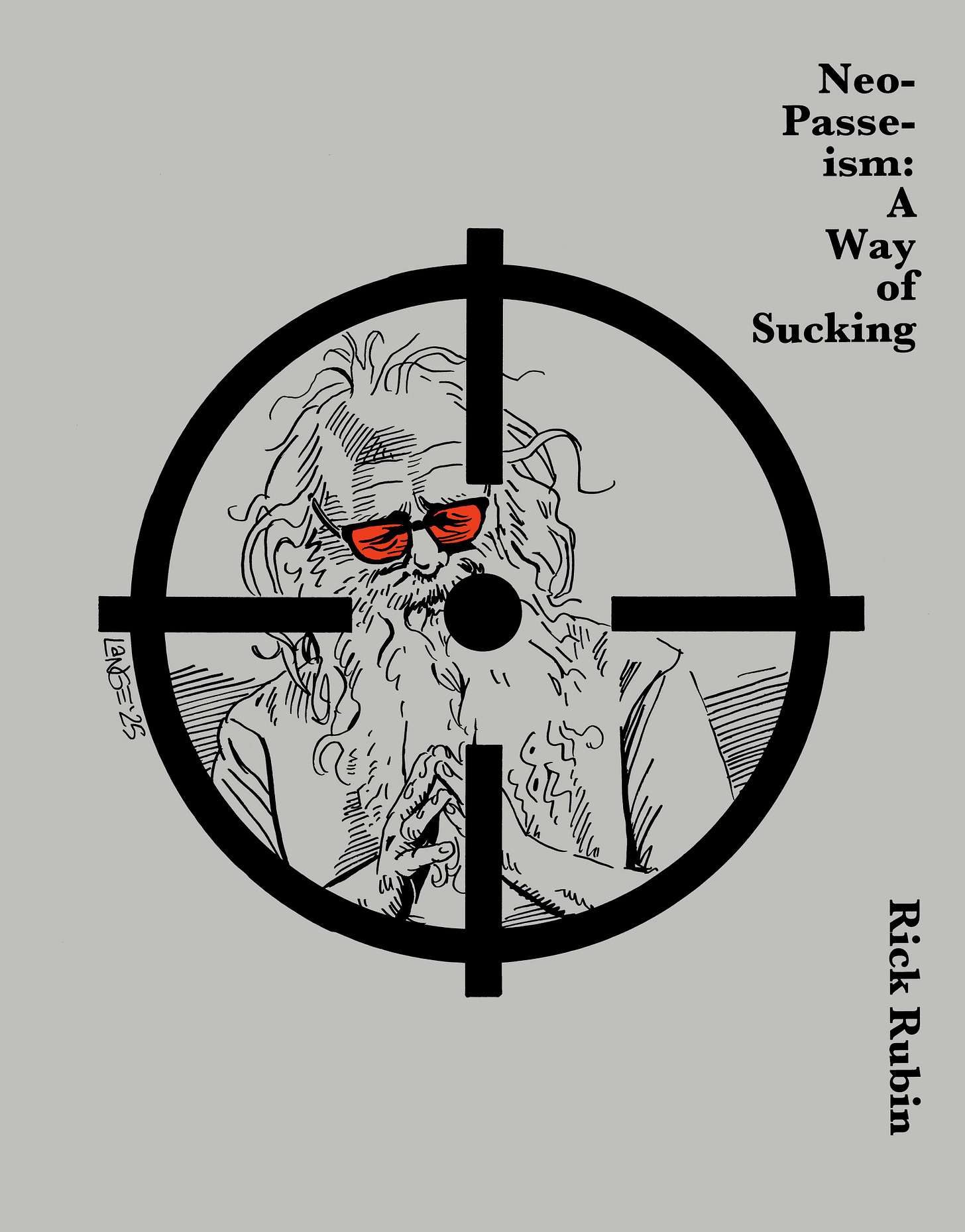

art by Aaron Lange and Dan Heyer

This obnoxious approach is observable later, in the 21st century, when folk-punk and bluegrass artists would cover gangster rap songs with Vain Irony, an extremely Neo-Passéist trait. We can see in those examples, and others like them, a direct consequence of the presence and principle of Rick Rubin.

I call the 1st Generation of producers genius trailblazers like TOM DOWD and GEOFF EMERICK with their 4-tracks. 2nd Generation lost the lab coats and got 8-tracks in return and thus could isolate the bass and give it its own treatment. Advanced channel and bus equalizers and dynamics became ubiquitous around this time. The best of these were the guys that understood that, when Punk came around, there was no proper way to operate the gear, and that you shouldn’t ask the guitar player, sans-master volume amplifier, to turn it down. The mic can go within a foot of the kick drum, or even inside it. Peaking valve gear is great, etc. The red light can be your friend. Splatter electrons. There is an idea amongst many Record Producers of the 2nd and 3rd Gens that they, through method, should put their stamp on a recording that makes it identifiable as coming out of their house. MUTT LANGE is a good example of this, for better or worse. PHIL SPECTOR is the classic example. More savvy Producers like BRENDAN O’BRIEN, who coincidentally was there for the debut and sophomore records spoken of above, developed studio methods that made their work identifiable as theirs to some degree, but only because of its high quality, or maybe some sneaky traits only easily identifiable by technicians. For example, O’Brien pioneered the use of a method of blending a live snare drum recording with a Pro Tools sound replaced sample. He had a massive library of custom-made samples, and ones snagged from multi-tracks of famous records he had made previously, the Golden Titties folder (shoutout to THE DUST BROTHERS). This blend can be heard by those looking for it, but it is not invasive. He also has an insane 3-hole Tweed Fender Deluxe amp that shows up on a lot of recordings. It’s easily identifiable if you know what it sounds like. The best example of it is STP’s “Interstate Love Song,” but I suspect it’s all over the sophomore record spoken of above as well, though Brendan did not Produce that record. These are only some examples.

AEROSMITH are maybe the best example of a Neo-Passéist band that welcomed over-Production. They were close trend-followers in the 1970s, mirroring earlier Glam and Arena rock successes of other bands, and as such became identifiable with a somewhat relevant cultural movement for a moment. This is while guitarist JOE PERRY was checked in. By the time you get past “Love in an Elevator” and get into the “Crazy,” “Amazing,” “Crying,” era of the band, they are literally doing DIANNE WARREN songs, the lady that wrote “My Heart Will Go On.” I can only imagine that Joe Perry was so checked out by this point that they had to pay him a lot of money to stick around. He had imagined his band as the next ROLLING STONES, and they ended up a perfect example of a casualty to the Producer. Also, I love sluts. I hate Aerosmith. Come to think of it, The Stones seem somehow immune to the presence of Producers. Maybe later, I don’t really know much about the second half of their career, but I guess that KEITH RICHARDS and MICK JAGGER were largely self-producing, as always with groundbreaking engineer/technicians like JIMMY MILLER around. Also, Stones handlers like ANDREW LOOG OLDMAN were classy enough not to take a Production credit after throwing Keith and Mick in a room and making them write songs together. If that had been Rick Rubin, he would have called it Production.

My clever little production generational thing ignores the classic definition of Producer in Hip-hop. KRS-ONE would tell me in 2008 when I produced vocals and effects for sessions that became “Adventures in MCing,” “Ryan, Ryan, slow down. You’re just the engineer. The Producer writes the maahfggn’ beat.” I don’t argue with the teacher.

I have negatively mentioned cultural appropriation a few times by this point but want to be clear; the Neo-Decadent does not have an ethical problem with someone outside any given culture borrowing from another culture’s artistic style or pantheon other than that it is potentially lazy and possibly a totally cynical commercial attempt to create interest in a product. Don’t read my use of this phraseology as virtue signaling. I am a white boy from the Southeast US; if I didn’t borrow from other cultures then I would be playing bluegrass with a Southern Cross on my wall. Or in Slayer.

This is not meant to totally disparage the A&R person. There are examples of responsible and ethical A&R that, though corporate in nature, served the artist in many ways. JAMES BARBER is the best example I can think of. Jim has impeccable taste and was in the right place at the right time in many cases, providing guidance for artists from BIG STAR to THE STROKES. Jim Produced some of RYAN ADAMS’s most relevant work in a way that wooed him away from the DAVID RAWLINGS and GILLIAN WELCH era of his career and onto something else. On Jim’s Substack Stars after Stars after Stars, which I highly recommend, he details his love for Athens, Georgia untouchables THE OLIVIA TREMOR CONTROL and how he went to a show at the ECHO LOUNGE in Atlanta with full intention of signing the band to GEFFEN RECORDS. He balked, however, suspecting that the bosses at the labels and the expensive mixing engineers would strangle the delicate WILL CULLEN HART and his band. Jim was likely right about Will and the band. He seems ambivalent about the decision, and laments “just how broke [the ELEPHANT 6] guys were”. It might have been a disaster. He was also right about the bosses. Forward to the present day where CHAPPELL ROAN has made much about being dropped by ATLANTIC RECORDS and later re-signed by ISLAND RECORDS (who inconsequentially and coincidentally now own DEF JAM, Rick’s former venture with Russell Simmons). Chappell herself puts this down to her hard work on performance in the meantime. I suspect that is true, mixed with a healthy dose of the evolution of the boss attitude that Jim alluded to; Executives now sign Pop Stars and give movie roles to the artists with the most social media followers. In-between deals Chappell Roan widened her social media reach and charmed the world with righteous femme domme energy. That’s why she got a new deal and a Grammy. See Jim’s Substack for more on Chappell’s greater victory and some inside tea on the Grammys from a former voter.

You know, I mostly agree with you but I do absolutely love the two albums he did with Trouble in the early 90s. Do I just have terrible taste or is a broken clock right twice a day/decade?

Rubin is a hack, he could never be a good producer unless he got as far away from a mixing console as possible. His productions are to music what being loud and thinking it makes you funny is to comedy.

Especially true because everything is so full of clipping from being cranked up so high during recording and mixing. It also doesn't help there seems to be a lot of overlap between the people who think he's an acceptable producer and the people who think loud = funny.